An epitope, also known as an antigenic determinant, is the part of an antigen that is recognized by the immune system, specifically by antibodies, B cells, and T cells. The latter can use epitopes to distinguish between different antigens, and only binds to their specific antigen. In antibodies, the binding site for an epitope is called a paratope. Although epitopes are usually derived from non-self proteins, sequences derived from the host that can be recognized are also classified as epitopes. Epitopes determine how antigen binding and antigen presentation occur.

Types of Antigenic Determinants

The epitopes of protein antigens are divided into two categories based on their structures and interaction with the paratope.

- A conformational epitope is composed of discontinuous sections of the antigen's amino acid sequence. These epitopes interact with the paratope based on the 3-D surface features and tertiary structure (overall shape) of the antigen. Most epitopes are conformational.

- Linear epitopes interact with the paratope based on their primary structure (shape of the protein's components). A linear epitope is formed by a continuous sequence of amino acids from the antigen, which creates a "line" of sorts that builds the protein structure.

Antigenic determinants recognized by B cells and the antibodies secreted by B cells can be either conformational or linear epitopes. Antigenic determinants recognized by T cells are typically linear epitopes. T cells do not recognize polysaccharide or nucleic acid antigens. This is why polysaccharides are generally T-independent antigens and proteins are generally T-dependent antigens. The determinants need not be located on the exposed surface of the antigen in its original form, since recognition of the determinant by T cells requires that the antigen be first processed by antigen presenting cells. Free peptides flowing through the body are not recognized by T cells, but the peptides associate with molecules coded for by the major histocompatibility complex (MHC). This combination of MHC molecules and peptide is recognized by T cells.

Antigen-Processing Pathways

In order for an antigen-presenting cell (APC) to present an antigen to a naive T cell, it must first be processed so itacan be recognized by the T cell receptor. This occurs within an APC that phagocytizes an antigen and then digests it through fragmentation (proteolysis) of the antigen protein, association of the fragments with MHC molecules, and expression of the peptide-MHC molecules at the cell surface. There, they are recognized by the T cell receptor on a T cell during antigen presentation. MHC molecules must move between the cell membrane and cytoplasm in order for antigen processing to occur properly. However, the pathway leading to the association of protein fragments with MHC molecules differs between class I and class II MHC, which are presented to cytotoxic or helper T cells respectively. There are two different pathways for antigen processing:

- The endogenous pathway occurs when MHC class I molecules present antigens derived from intracellular (endogenous) proteins in the cytoplasm, such as the proteins produced within virus-infected cells. Generally, proteosomes are used to break up the viral proteins and combine them with MHC I.

- The exogenous pathway occurs when MHC class II molecules present fragments derived from extracellular (exogenous) proteins that are located within the cell. First, pathogens are phagocytized, then endosomes within the cell break down antigens with proteases, which then combine with MHC II.

Some viral pathogens have developed ways to evade antigen processing. For example, cytomegalovirus and HIV-infected cells sometimes disrupt MHC movement through the cytoplasm, which may prevent them from binding to antigens or from moving back to the cell membrane after binding with an antigen.

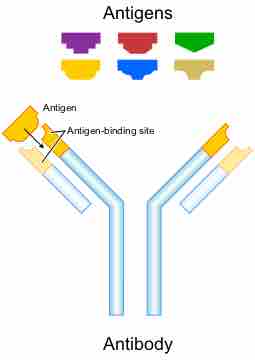

Antigen-Binding Site of an Antibody

Antigen-binding sites can recognize different epitopes on an antigen.