Stress typically describes a negative concept that can have an impact on one's mental and physical well-being, but it is unclear what exactly defines stress and whether or not stress is a cause, an effect, or the process connecting the two. With organisms as complex as humans, stress can take on entirely concrete or abstract meanings with highly subjective qualities, satisfying definitions of both cause and effect in ways that can be both tangible and intangible.

Physiologists define stress as how the body reacts to a stressor (any stimulus that causes stress), real or imagined. Acute stressors affect an organism in the short term; chronic stressors over the long term.

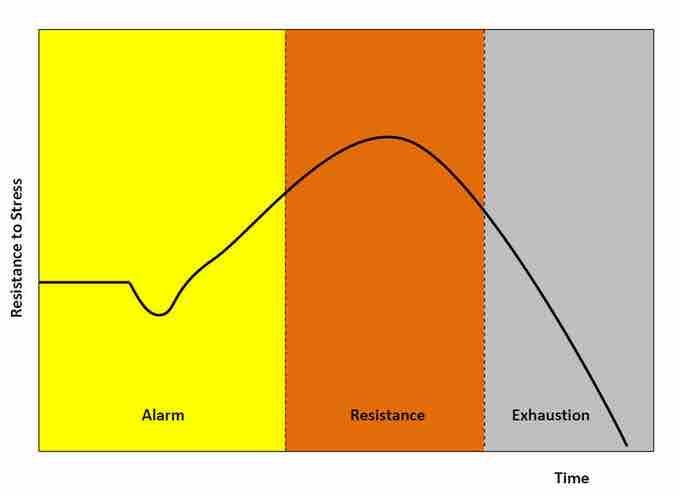

Alarm Stage

Alarm is the first stage, which is divided into two phases: the shock phase and the anti-shock phase.

Shock Phase

During this phase, the body can endure changes such as hypovolemia, hypoosmolarity, hyponatremia, hypochloremia, and hypoglycemia—the stressor effect. The organism's resistance to the stressor drops temporarily below the normal range and some level of shock (e.g., circulatory shock) may be experienced.

Anti-Shock Phase

When the threat or stressor is identified or realized, the body starts to respond and is in a state of alarm. During this stage, the locus coeruleus/sympathetic nervous system is activated and catecholamines such as adrenaline are produced to create the fight-or-flight response.

The result is: increased muscular tonus, increased blood pressure due to peripheral vasoconstriction and tachycardia, and increased glucose in blood. There is also some activation of the HPA axis, producing glucocorticoids such as cortisol.

Resistance Stage

Resistance is the second stage and the increased secretion of glucocorticoids plays a major role by intensifying the systemic response. This response has lypolytic, catabolic, and antianabolic effects: increased glucose, fat and amino acid/protein concentration in blood.

Moreover, these effects cause lymphocytopenia, eosinopenia, neutrophilia, and polycythemia. In high doses, cortisol begins to act as a mineralocorticoid (aldosteron) and brings the body to a state similar to hyperaldosteronism.

If the stressor persists, it becomes necessary to attempt some means of coping with the stress. Although the body begins to try to adapt to the strains or demands of the environment, the body cannot keep this up indefinitely, so its resources are gradually depleted.

Exhaustion or Recovery Stage

The third stage is either exhaustion or recovery.

General adaptation syndrome

Resistance reaction is the second stage of the general adaptation syndrome and is characterized by a heightened resistance to a stressor.