The hypothalamus (derived from the Greek for "under chamber") is a portion of the brain that contains a number of small, distinct nuclei with various functions and less anatomically distinct areas. The hypothalamus is located below the thalamus just above the brain stem. In the terminology of neuroanatomy, it forms the ventral part of the diencephalon. All vertebrate brains contain a hypothalamus. In humans, it is roughly the size of an almond.

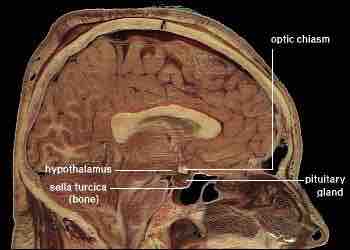

Location of the hypothalamus

This is the location of the human hypothalamus in relation to the thalamus, pituitary gland, sella turcica, and optic chiasm.

The location of hypothalamus and pituitary

At center, hypothalamus is located just superior to the pituitary, with which it closely interacts.

General Functions

One of the most important functions of the hypothalamus is linking the nervous system to the endocrine system via the pituitary gland (hypophysis).

The hypothalamus contains thyrotropin-releasing hormone, gonadotropin-releasing hormone, growth hormone-releasing hormone, corticotropin-releasing hormone, somatostatin, and dopamine, as well as vasopressin and oxytocin. These hormones are released into the bloodstream and target other organ systems, most notably the pituitary. The hypothalamus affects the endocrine system and governs emotional behavior such as anger and sexual activity. Most of the hypothalamic hormones generated are distributed to the pituitary via the hypophyseal portal system. The hypothalamus maintains homeostasis, including the regulation of blood pressure, heart rate, and temperature.

The hypothalamus coordinates hormonal and behavioral circadian rhythms, complex patterns of neuroendocrine outputs, complex homeostatic mechanisms, and important behaviors. It must therefore respond to many different signals, some of which are generated externally and some internally. The hypothalamus is thus richly connected with many parts of the central nervous system, including the brainstem, reticular formation and autonomic zones, and the limbic forebrain (particularly the amygdala, septum, diagonal band of Broca, olfactory bulbs, and cerebral cortex). The hypothalamus can sample the blood composition at the subfornical organ and the organum vasculosum of the lamina terminalis. This is important for the uptake of circulating hormones and to determine concentration of substances in the blood.

Temperature Regulation

The hypothalamus functions as a type of thermostat for the body. It sets a desired body temperature and stimulates either heat production and retention to raise the blood temperature to a higher level, or sweating and vasodilation to cool the blood to a lower temperature. All fevers result from a raised setting in the hypothalamus; elevated body temperatures due to any other cause are classified as hyperthermia. Rarely, direct damage to the hypothalamus such as from a stroke causes a fever; this is sometimes called a hypothalamic fever. However, such damage more commonly causes abnormally low body temperatures.

Appetite

The extreme lateral part of the ventromedial nucleus of the hypothalamus is responsible for control of food intake. Stimulation of this area causes increased food intake. Bilateral lesion in this area causes complete cessation of food intake. Medial parts of the nucleus have a controlling effect on the lateral part. Bilateral lesion of the medial part of the ventromedial nucleus causes hyperphagia and obesity. Further lesion of the lateral part of the ventromedial nucleus in the same animal produces complete cessation of food intake.

Fear Processing

The medial zone of hypothalamus is part of a circuitry that controls motivated behaviors, such as defensive behaviors and social defeat. Analyses of Fos-labeling showed that a series of nuclei in the behavioral control column is important in regulating the expression of innate and conditioned defensive behaviors. Nuclei in the medial zone are also mobilized during an encounter with an aggressor. The defeated animal has an increase in Fos levels in sexually dimorphic structures.

Sexual Dimorphism

Several hypothalamic nuclei are sexually dimorphic, with clear differences in both structure and function between males and females. Some differences are apparent even in gross neuroanatomy, most notably is the sexually dimorphic nucleus within the preoptic area. However, most are subtle changes in the connectivity and chemical sensitivity of particular sets of neurons. In neonatal life, gonadal steroids influence the development of the neuroendocrine hypothalamus. For instance, they determine the ability of females to exhibit a normal reproductive cycle and of males and females to display appropriate reproductive behaviors in adult life.

In 2004 and 2006, two studies by Berglund, Lindström, and Savic used Positron Emission Tomography (PET) to observe how the hypothalamus responds to smelling common odors, the scent of testosterone found in male sweat, and the scent of estrogen found in female urine. These studies showed that the hypothalamus of heterosexual men and homosexual women both respond to estrogen. Also, the hypothalamus of homosexual men and heterosexual women both respond to testosterone. In all four groups, common odors were processed similarly involving only the olfactory brain.