Acid–base imbalance occurs when a significant insult causes the blood pH to shift out of the normal range (7.35 to 7.45). An excess of acid in the blood is called acidemia and an excess of base is called alkalemia. The process that causes the imbalance is classified based on the etiology of the disturbance (respiratory or metabolic) and the direction of change in pH (acidosis or alkalosis). There are four basic processes: metabolic acidosis, respiratory acidosis, metabolic alkalosis, and respiratory alkalosis. One or a combination may occur at any given time.

Blood carries oxygen, carbon dioxide, and hydrogen ions (H+) between tissues and the lungs. The majority of CO2 transported in the blood is dissolved in plasma (primarily as dissolved bicarbonate; 60%). A smaller fraction is transported in red blood cells combined with the globin portion of hemoglobin as carbaminohemoglobin. This is the chemical portion of the red blood cell that aids in the transport of oxygen and nutrients around the body, but, this time, it is carbon dioxide that is transported back to the lung.

Acid–base imbalances that overcome the buffer system can be compensated in the short term by changing the rate of ventilation. This alters the concentration of carbon dioxide in the blood, shifting the above reaction according to Le Chatelier's principle, which in turn alters the pH. The basic reaction governed by this principle is as follows:

H2O + CO2 <--> H2CO3 <--> H+ + CO3-

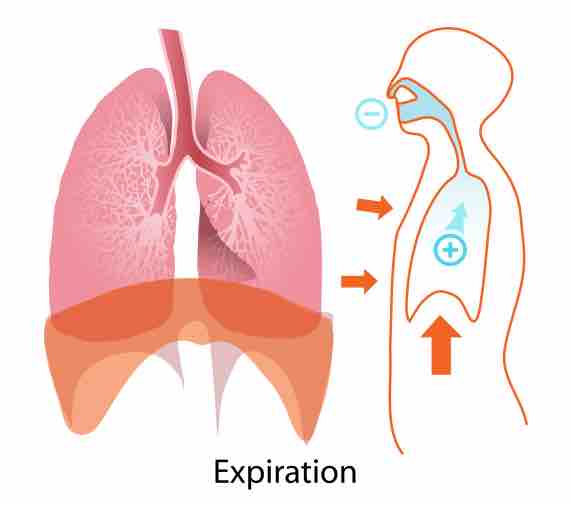

When blood pH drops too low (acidemia), the body compensates by increasing breathing thereby expelling CO2, shifting the above reaction to the left such that less hydrogen ions are free; thus the pH will rise back to normal. For alkalemia, the opposite occurs.

Expiration

When blood pH drops too low, the body compensates by increasing breathing to expel more carbon dioxide.