Smell

At birth, infants can show different expressions of disgust or pleasure when presented with pleasant odors (honey, milk, etc.) or unpleasant odors (rotten egg) and tastes (e.g. sour taste). Newborns are born with odor and taste preferences acquired in the womb from the smell and taste of amniotic fluid, which, in turn, is influenced by what the mother eats.

Intrauterine olfactory learning may be demonstrated by behavioral evidence that newborn infants respond positively to the smell of their own amniotic fluid. Infants are responsive to the olfactory cues associated with maternal breast odors. They are able to recognize and react favorably to scents emitted from their own mother's breasts, despite the fact that they also may be attracted to breast odors from unfamiliar nursing females in a different context. The unique scent of the mother (to the infant) is referred to as her olfactory signature. While breasts are a source of the unique olfactory cue of the mother, infants are also able to recognize and respond with familiarity and preference to their mother's underarm scent.

As demonstrated by animals in the wild (the great apes, for example), the offspring is held by the mother immediately after birth without cleaning and is continually exposed to the familiar odor of the amniotic fluid (making the transition from the intrauterine to extrauterine environment less overwhelming). In newborn mammals, the nipple area of the mother is significant as the sole source of necessary nutrients. The maternal olfactory scent that is unique to the mother becomes associated with food intake. Newborns who do not gain access to the mother's breasts would die shortly after birth. As a result, it seems natural selection should favor the development of a means to help maintain and establish effective breast feeding. Maternal breast odors signal the presence of a food source for the newborn. These breast odors bring forth positive responses in neonates from as young as one hour or less through several weeks postpartum. The mother's olfactory signature is experienced with reinforcing stimuli such as food, warmth, and tactile stimulation, enhancing further learning of that cue.

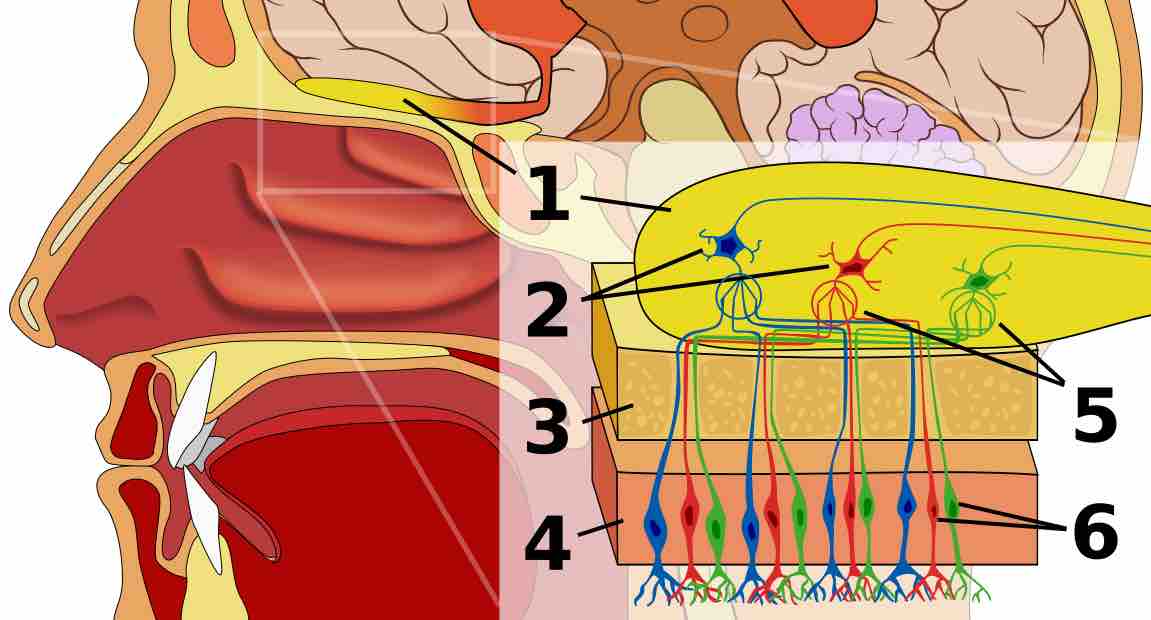

Studies demonstrate that the changes to the olfactory bulb and main olfactory system following birth are extremely important and influential for maternal behavior. A diagram of the olfactory system is shown in . Pregnancy and childbirth result in a high state of plasticity of the olfactory system that may facilitate olfactory learning within the mother. Neurogenesis likely facilitates the formation of olfactory memory in the mother, as well as the infant. A significant change takes place in the regulation of olfaction just after birth so that odors related with the offspring are no longer aversive, allowing the female to positively respond to her babies.

Olfactory System

Human olfactory system. 1: Olfactory bulb 2: Mitral cells 3: Bone 4: Nasal epithelium 5: Glomerulus (olfaction) 6: Olfactory receptor cells

Older people experience a decline in the sense of smell. Anosmia, a lack of functioning olfaction (inability to perceive odors), may be temporary, but traumatic anosmia can be permanent. Anosmia is due to an inflammation of the nasal mucosa, blockage of nasal passages, or a destruction of one temporal lobe. A common cause of anosmia is old age.

Taste

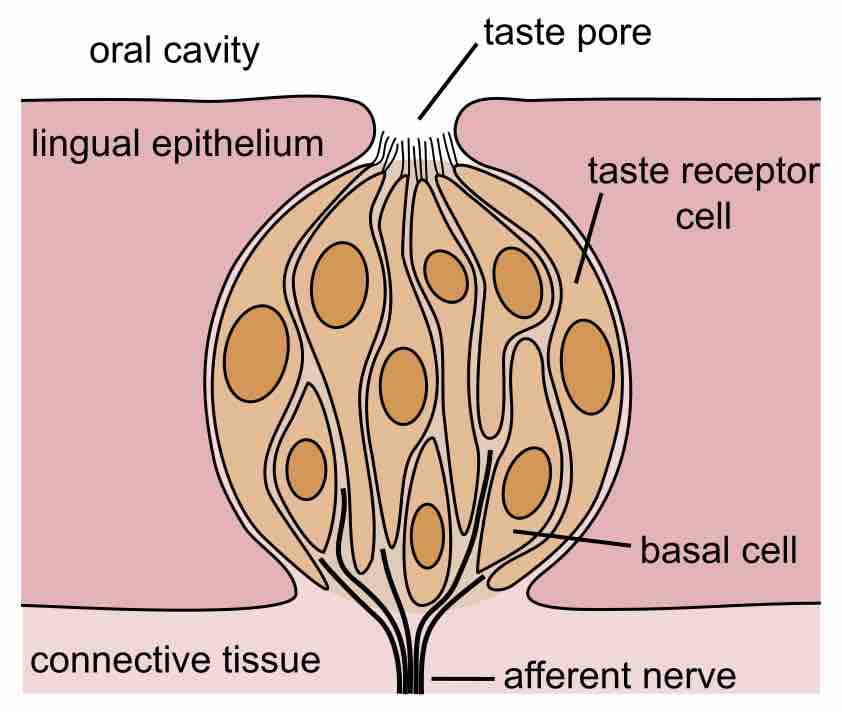

Taste buds contain the receptors for taste and are located around the small structures (papillae) on the upper surface of the tongue, soft palate, upper esophagus, and epiglottis. These papillae are involved in detecting the five (known) elements of taste perception: salty, sour, bitter, sweet, and umami. Via small openings in the tongue epithelium (taste pores) parts of the food dissolved in saliva come into contact with taste receptors (taste buds). The taste receptor cells send information detected by clusters of various receptors and ion channels to the gustatory areas of the brain via the seventh, ninth, and tenth cranial nerves. On average, the human tongue has 2,000–8,000 taste buds. The structure of taste receptors in humans is shown in .

Taste Receptors in Humans

Structure of the taste bud

The average life of a taste bud is 10 days. Ageusia is the loss of taste functions of the tongue, particularly the inability to detect sweetness, sourness, bitterness, saltiness, and umami (meaning "pleasant/savory taste"). It is sometimes confused with anosmia: a loss of the sense of smell. Because the tongue can only indicate texture and differentiate between sweet, sour, bitter, salty, and umami, most of what is perceived as the sense of taste is actually derived from smell. True ageusia is relatively rare compared to hypogeusia (a partial loss of taste) and dysgeusia (a distortion or alteration of taste). Local damage and inflammation that interferes with the taste buds or local nervous system such as that stemming from radiation therapy, glossitis, tobacco use, and denture use (which is associated with old age) also cause ageusia. Other known causes include loss of taste sensitivity from aging (causing a difficulty detecting salty or bitter taste), anxiety disorder, cancer, renal failure and liver failure.