Bacillus subtilis is a rod-shaped, Gram-postive bacteria that is naturally found in soil and vegetation. It is known for its ability to form a small, tough, protective, and metabolically dormant endospore. B. subtilis can divide symmetrically to make two daughter cells (binary fission), or asymmetrically, producing a single endospore that is resistant to environmental factors such as heat, desiccation, radiation, and chemical insult which can persist in the environment for long periods of time. The endospore is formed at times of nutritional stress, allowing the organism to persist in the environment until conditions become favourable. The process of endospore formation has profound morphological and physiological consequences: radical post-replicative remodeling of two progeny cells, accompanied eventually by cessation of metabolic activity in one daughter cell (the spore) and death by lysis of the other (the ‘mother cell').

B. subtillis

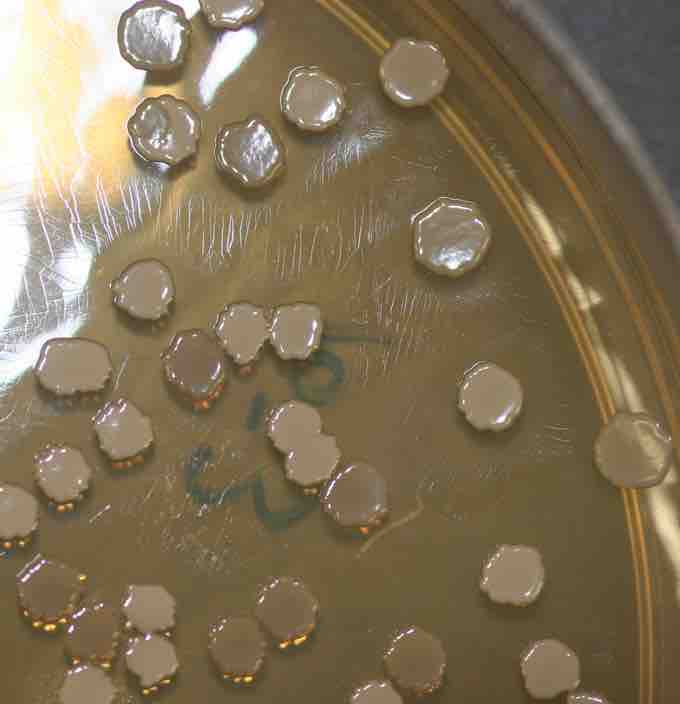

Colonies of B. subtilis grown on a culture dish in a molecular biology laboratory.

Although sporulation in B. subtilis is induced by starvation, the sporulation developmental program is not initiated immediately when growth slows due to nutrient limitation. A variety of alternative responses can occur:

- The activation of flagellar motility to seek new food sources by chemotaxis

- The production of antibiotics to destroy competing soil microbes

- The secretion of hydrolytic enzymes to scavenge extracellular proteins and polysaccharides, or the induction of ‘competence' for uptake of exogenous DNA for consumption, with the occasional side-effect that new genetic information is stably integrated.

Sporulation is a last-ditch response to starvation, and it is suppressed until alternative responses prove inadequate. Even then, certain conditions must be met, such as chromosome integrity, the state of chromosomal replication, and the functioning of the Krebs cycle.

Sporulation requires a great deal of time and energy, and it is essentially irreversible, making it crucial for a cell to monitor its surroundings efficiently and ensure that sporulation is embarked upon at only the most appropriate times. The wrong decision can be catastrophic: a vegetative cell will die if the conditions are too harsh, while bacteria-forming spores in an environment which is conducive to vegetative growth will be outcompeted. In short, initiation of sporulation is a very tightly regulated network with numerous checkpoints for efficient control.

Two transcriptional regulators, σH and Spo0A, play key roles in initiation of sporulation. Several additional proteins participate, mainly by controlling the accumulated concentration of Spo0A~P. Spo0A lies at the end of a series of inter-protein phosphotransfer reactions, Kin–Spo0F–Spo0B–Spo0A, termed as a ‘phosphorelay'.