Iron (Fe) follows a geochemical cycle like many other nutrients. Iron is typically released into the soil or into the ocean through the weathering of rocks or through volcanic eruptions.

The Terrestrial Iron Cycle: In terrestrial ecosystems, plants first absorb iron through their roots from the soil. Iron is required to produce chlorophyl, and plants require sufficient iron to perform photosynthesis. Animals acquire iron when they consume plants, and iron is utilized by vertebrates in hemoglobin, the oxygen-binding protein found in red blood cells. Animals lacking in iron often become anemic and cannot transmit adequate oxygen. Bacteria then release iron back into the soil when they decompose animal tissue.

The Marine Iron Cycle: The oceanic iron cycle is similar to the terrestrial iron cycle, except that the primary producers that absorb iron are typically phytoplankton or cyanobacteria. Iron is then assimilated by consumers when they eat the bacteria or plankton. The role of iron in ocean ecosystems was first discovered when English biologist Joseph Hart noticed "desolate zones," which are regions that lacked plankton but were rich in nutrients. He hypothesized that iron was the limiting nutrient in these areas. In the past three decades there has been research into using iron fertilization to promote alagal growth in the world's oceans. Scientists hoped that by adding iron to ocean ecosystems, plants might grown and sequester atmospheric CO2. Iron fertilization was thought to be a possible method for removing the excess CO2 responsible for climate change. Thus far, the results of iron fertilization experiments have been mixed, and there is concern among scientists about the possible consequences of tampering nutrient cycles .

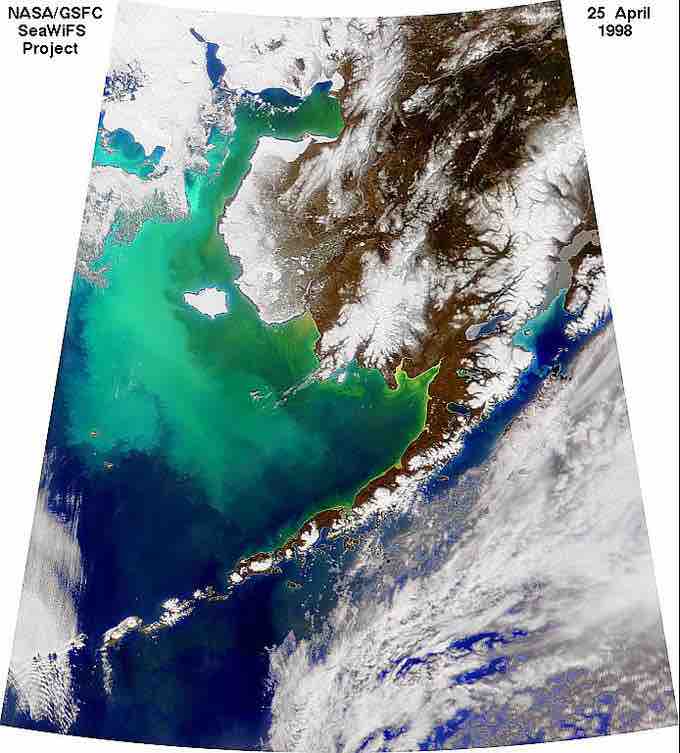

Algal bloom

Algae bloom in the Bering Sea after a natural iron fertilization event.