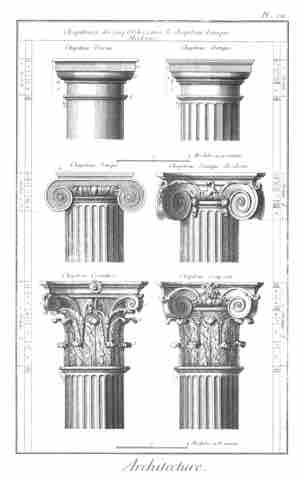

Roman architecture began as an imitation of Classical Greek architecture but eventually evolved into a new style. Unfortunately, almost no early Republican buildings remain intact. The earliest substantial remains date to approximately 100 BCE. Innovations such as improvements to the round arch and barrel vault, as well as the inventions of concrete and the true hemispherical dome, allowed Roman architecture to become more versatile than its Greek predecessors. While the Romans were reluctant to abandon classical motifs, they modified such elements as temple design by abandoning pedimental sculptures, altering the traditional Greek peripteral colonnades, and opting for central exterior stairways. Likewise, although Roman architects did not abandon traditional column orders, they did modify the them with the Tuscan, Roman Ionic, and Composite orders. This diagram shows the Greek orders on the left and their Roman modifications on the right.

Greek and Roman column orders

From top to bottom: Doric and Tuscan, Ionic and Roman Ionic (scrolls on all four corners), Corinthian and Composite.

Roman Temples

Most Roman temples derived from Etruscan prototypes. Like Etruscan temples, Roman temples are frontal with stairs leading up to a podium and a deep portico filled with columns. They are also usually rectilinear, and the interiors consist of at least one cella, which contained a cult statue.

If multiple gods were worshiped in one temple, each god would have its own cella and cult image. For example, Capitolia, temples dedicated to the Capitoline Triad, would always be built with three cellae, one for each god of the triad: Jupiter, Juno, and Minerva. Roman temples were typically made of brick and concrete and then faced in either marble or stucco. Engaged columns (columns that protrude from walls like reliefs) adorn the exteriors of the temples. This creates an effect of columns completely surrounding a cella, an effect known as psuedoperipteral. The altar, used for sacrifices and offerings, always stood outside in front of the temple.

Temple of Portunus

A typical Roman Republican temple. Rome. c. 75 BCE.

While most Roman temples followed this typical plan, some were dramatically different. At times, the Romans erected round temples that imitated the Greek tholos. Examples can be found in the Temple of Hercules Victor (late second century BCE), in the Forum Boarium in Rome. The temple consists a circular cella within a concentric ring of 20 Corinthian columns. Like its Etruscan predecessors, the temple rests on a tufa foundation. Its original roof and architrave are now lost.

Temple of Hercules Victor

A Roman modification of a Greek tholos. Rome. Late second century BCE.

Concrete

The Romans perfected the recipe for concrete during the third century BCE by mixing together water, lime, and pozzolana, volcanic ash mined from the countryside surrounding Mt. Vesuvius. Concrete became the primary building material for the Romans, and it is largely the reason that they were such successful builders. Most Roman buildings were built with concrete and brick that was then covered in façade of stucco, expensive stone, or marble. Concrete was a cheaper and lighter material than most stones used for construction. This helped the Romans build structures that were taller, more complicated, and quicker to build than any previous ones. Once dried, concrete was also extremely strong, yet flexible enough to remain standing during moderate seismic activity. The Romans were even able to use concrete underwater, allowing them build harbors and breakers for their ports. The ruins of a tomb on the Via Appia (the most famous thoroughfare through ancient Rome) expose the stones and aggregate that the Romans used to mix concrete.

Wall of a tomb on the Via Appia, Rome.

The ruins show the internal core of the building, made in roman concrete.

Arches, Vaults, and Domes

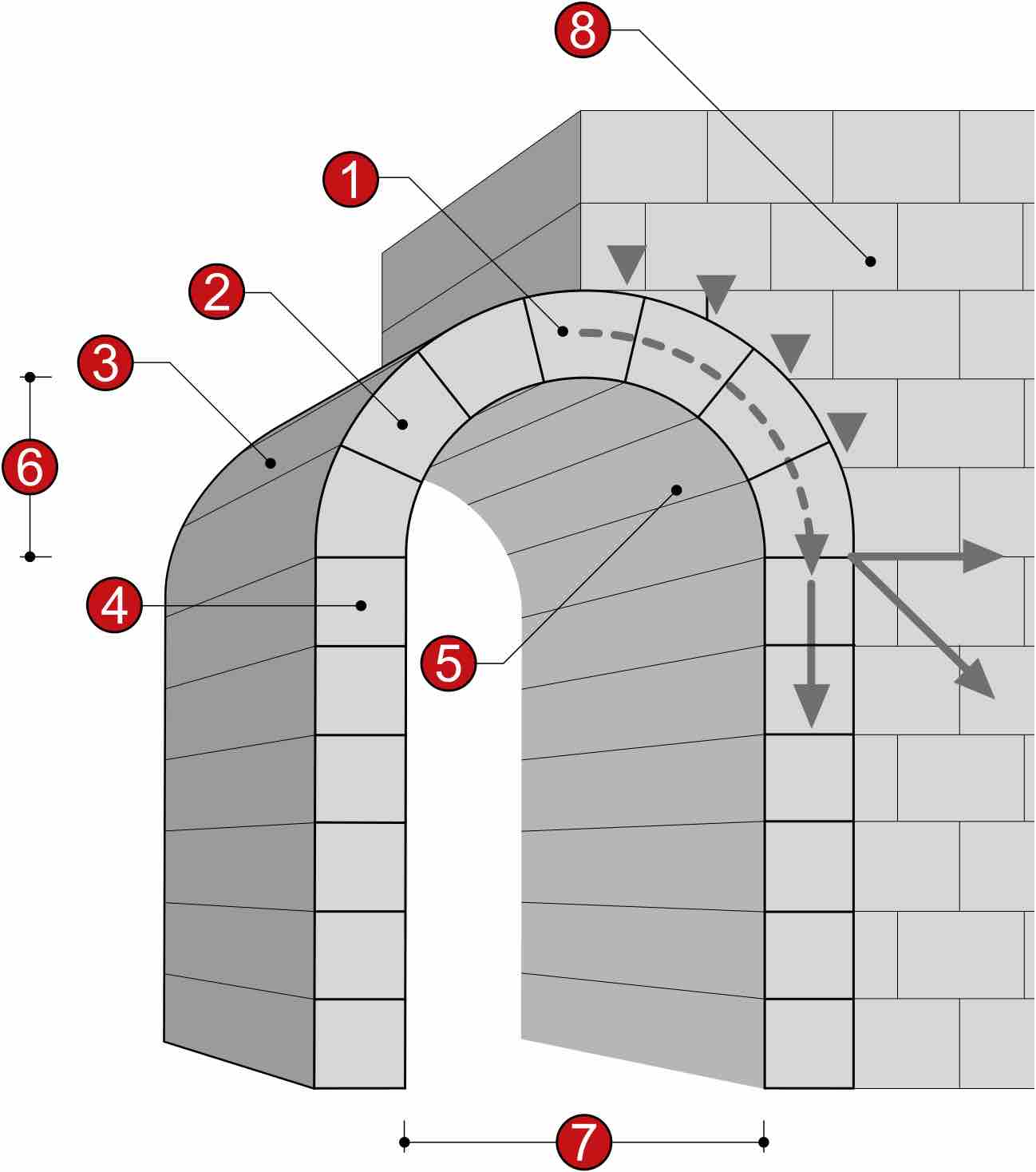

The Romans effectively combined concrete and the structural shape of the arch. These two elements became the foundations for most Roman structures. Arches can bear immense weight, as they are designed to redistribute weight from the top, to its sides, and down into the ground. While the Romans did not invent the arch, they were the first culture to manipulate and readily rely on its shape. An arch is a pure compression form. It can span a large area by resolving forces into compressive stresses (pushing downward) and, in turn eliminating tensile stresses (pushing outward). As the forces in the arch are carried to the ground, the arch will push outward at the base, called thrust. As the height of the arch decreases, the outward thrust increases. In order to maintain arch action and prevent the arch from collapsing, the thrust needs to be restrained, either with internal ties or external bracing, such as abutments (labeled 8 on the diagram below).

Schematic illustration of an arch.

This diagram illustrates the structural support of an arch extended into a barrel vault. The dotted line extending downward from the keystone (1) shows the strength of the arch directing compressive stresses (represented by the downward-pointing arrows outside the arch) safely to the ground. Meanwhile, tensile stress (represented by the horizontal and diagonal-facing arrows) is contained by the surrounding wall.

The arch is a shape that can be manipulated into a variety of forms that create unique architectural spaces. Multiple arches can be used together to create a vault. The simplest type is known as a barrel vault. Barrel vaults consist of a line of arches in a row that create the shape of a tunnel. When two barrel vaults intersect at right angles, they create a groin vault. These are easily identified by the x-shape they create in the ceiling of the vault. Furthermore, because of the direction, the thrust is concentrated along this x-shape, so only the corners of a groin vault need to be grounded. This allows an architect or engineer to manipulate the space below the groin vault in a variety of ways.

Arches and vaults can be stacked and intersected with each other in a multitude of ways. One of the most important forms that they can create is the dome. This is essentially an arch that is rotated around a single point to create a large hemispherical vault. The largest dome constructed during the Republic was on the Temple of Echo at Baiae, named for its remarkable acoustic properties.

Temple of Echo at Baiae.

The dome on Temple of Echo at Baiae creates the building’s remarkable acoustic properties.

The arch and concrete are found in many iconic Roman structures. The Sanctuary of Fortuna Primigenia at Palestrina (c. 120 BCE), Italy is a massive temple structure built into the hillside in first century BCE in a series of terraces, exedras, and porticoes. Concrete was used as the primary building material and barrel vaults provide structural support both as a terracing method for the hill and in creating interesting architectural spaces for the sanctuary.

Sanctuary of Fortuna Primigenia (scale model)

Palestrina, Italy. c. 120 BCE.

Roman aqueducts are another iconic use of the arch. The arches that make up an aqueduct provided support without requiring the amount of building material necessary for arches supported by solid walls. The Aqua Marcia (144–140 BCE) was the longest of the eleven aqueducts that served the city of Rome during the Republic. It supplied water to the Viminal Hill in the north of Rome, and from there to the Caelian, Aventine, Palatine, and Capitoline Hills. Where the Aqua Marcia had contact with water, it was coated with a waterproof mortar.

Aqua Marcia

Ruins near Tivoli, Italy. 144–140 BCE.