During his reign, Augustus enacted an effective propaganda campaign to promote the legitimacy of his rule as well as to encourage moral and civic ideals among the Roman populace.

Augustan sculpture contains rich iconography of Augustus's reign with strong themes of legitimacy, stability, fertility, prosperity, and religious piety. The visual motifs employed within this iconography became the standards for imperial art.

Ara Pacis Augustae

The Ara Pacis Augustae, or Altar of Augustan Peace, is one of the best examples of Augustan artistic propaganda. Not only does it demonstrate a new moral code promoted by Augustus, but it also established imperial iconography. It was commissioned by the Senate in 13 BCE to honor the peace and bounty established by Augustus following his return from Hispania (Spain) and Gaul and it was consecrated on January 30, 9 BCE. The marble altar was erected just outside the boundary of the Pomerium to the north of the city along the Via Flaminia on the Campus Martius. The actual u-shaped altar sits atop a podium inside a square wall that demarcates the precinct's sacred space.

Ara Pacis Augustae

View from the northeast. Marble, 13-9 BCE, Rome, Italy.

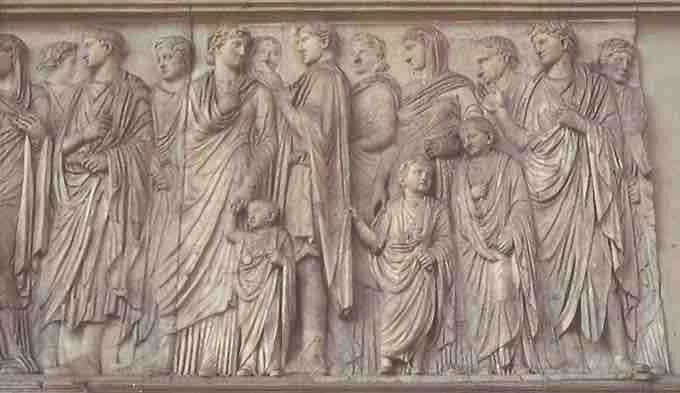

The north and south walls depict a procession of life-sized figures on the upper register. These figures include men, women, children, priests, lictors, and identifiable members of the political elite during the Augustan age, including Augustus, his wife Livia, his son-in-law Marcus Agrippa (who died in 12 BCE), and Tiberius, Augustus's adopted son and successor who would marry the emperor's widowed daughter in 11 BCE. While the altar as a whole celebrates the Augustus as a peacemaker, this scene in particular promotes him as a pious family man.

Ara Pacis Augustae

Detail from the processional scene on the south wall. Marble. 13-9 BCE. Rome, Italy.

Imperial Portraiture

Augustus very carefully controlled his imperial portrait. Abandoning the veristic style of the Republican period, his portraits always showed him as an idealized young man. These portraits linked him to divinities and heroes, both mythical and historical. He is often shown with an identifiable cowlick that was originally shown on the portraits of Alexander the Great. His lack of shoes signifies his supposed humbleness despite the great power he possessed. Two portraits of him, one as Pontifex Maximus and the other as Imperator, depict two different personae of the emperor. Augustus's portrait as Pontifex Maximus shows him attired with a toga over his ever-youthful head, an attribute that serves to remind viewers of his own extreme piety to the gods.

Augustus

Portrayed as Pontifex Maximus.

The Augustus of Primaporta shows influence of both Roman and Classical Greek works, including the Spear Bearer by Polykleitos and the Etruscan bronze Aule Metele. Assuming the role of imperator, Augustus wears military grab in a pose known as adlucotio, addressing his troops. Despite his poor health, which left him with a frail body, he appears healthy and muscular. At his feet Cupid rides a dolphin, a symbol of his divine ancestry. Cupid is the son of Venus, as was Aeneas, the legendary ancestor of the Roman people. The Julian family traced their ancestry back to Aeneas and, therefore, consider themselves descendants of Venus. As Caesar's nephew and adopted son, this use of iconography allows Augustus to remind viewers of his divine lineage. In addition to his adopting the body language and attire of a general, the relief on the cuirass shows one of Augustus's greatest victories—the return of the Parthian standards. During the civil wars, a legion's standards were lost when the legion was defeated by the Parthians. In a great feat of diplomacy, and curiously not military action, Augustus was able to negotiate the return of the standards to the legion and to Rome. Additional figures on the cuirass personify Roman gods and the arrival of Augustan peace.

Augustus of Primaporta

c. 20 BCE, marble, Primaporta, Italy.

The Legacy of Augustan Sculpture

Upon the death of Augustus, Tiberius (r. 14-37 CE) assumed the title of emperor and Pontifex Maximus of Rome. Like his father-in-law, Tiberius maintained a youthful appearance in his portraiture in sculpture. A general in his pre-imperial career, Tiberius appears in a sculpture very similar to the Augustus of Primaporta. He wears military attire and stands erect in a dynamic contrapposto pose with his arm raised. Although he wears boots, which would appear to contradict the suggestion of humbleness seen in full-length sculptures of Augustus, his plain cuirass and the absence of religious iconography suggest a competent leader who does not promote his accomplishments or divine ancestry.

Full-length sculpture of Tiberius in military garb.

Like Augustus, who suffered from poor health, Claudius, who succeeded Caligula in 41 CE, was also infirm. In addition to health issues, Claudius lacked experience as a leader but quickly overcame this shortcoming as emperor. During his reign, Rome annexed the province of Britannia (present-day England and Wales) and witnessed the construction of new roads and aqueducts. Despite these achievements, Claudius's opponents still saw him as vulnerable, a situation that forced him to shore up his position almost constantly, resulting in the deaths of many senators. Perhaps this need to prove his competency in his role prompted him to commission a sculpture of himself as Jupiter, a sculpture that also bears striking similarities to the Augustus of Primaporta. He continues the standard of the eternally youthful and healthy emperor begun by Augustus. His face and body are idealized. Like his predecessor, Claudius appears barefoot in a gesture of humility balanced with a symbol of divinity, in this case, an eagle to symbolize Jupiter. He wears a laurel crown as a metaphor of victory. While the positions of his arms and hand are similar to those of Augustus, Claudius holds a bowl (an offering to signify his piety) in one hand and a scepter-like object (to signify his power) in the other.