Early Roman art was influenced by the art of Greece and that of the neighboring Etruscans, themselves greatly influenced by their Greek trading partners. As the expanding Roman Republic began to conquer Greek territory, official sculpture became largely an extension of the Hellenistic style, with its departure from the idealized body and flair for the dramatic. This is partly due to the large number of Greek sculptors working within Roman territory. However, Roman sculpture during the Republic departed from Greek traditions in several ways. It was the first to feature a new technique called continuous narration. Commoners, including freedmen, could commission public art and use it to cast their professions in a positive light. Portraiture throughout the Republic celebrated old age with its verism. Finally, in the closing decades of the Republic, Julius Caesar counteracted traditional propriety by becoming the first living person to place his own portrait on a coin. In the examples that follow, the patrons use these techniques to promote their status in society.

The Altar of Domitius Ahenobarbus

Despite its most common title, the "Altar" of Domitius Ahenobarbus (late second century BCE) was more likely a base intended to support cult statues in the cella of a Temple of Neptune (Poseidon) located in Rome on the Field of Mars. The frieze is t the second oldest Roman bas-relief currently known. Domitius Ahenobarbus, a naval general, likely commissioned the altar and the temple in gratitude of a naval victory between 129 and 128 BCE. The reliefs combine mythology and contemporary civic life.

One panel of the "altar" depicts the census, a uniquely Roman event of contemporary civic life. It is one of the earliest reliefs sculpted in continuous narration, in which the viewer "reads" from left to right the recording of the census, the purification of the army before the altar of Mars, and the levy of the soldiers.

Altar of Domitius Ahenobarb. Late second century BCE.

Census scene.

The other three panels depict the mythological wedding of Neptune and Amphitrite. At the center of his scene, Neptune and Amphitrite are seated in a chariot drawn by two Tritons (messengers of the sea) who dance to music. They are accompanied by a multitude of fantastic creatures, Tritons and Nereides (sea nymphs) who form a retinue for the wedding couple, which, like the census scene, can be read from left to right. At the left, a Nereid riding on a sea-bull carries a present. Next, Amphitrite's mother Doris advances towards the couple, mounted on a hippocampus (literally, a sea horse) and holding wedding torches in each hand to light the procession's way. Eros hovers behind her. Behind the wedding couple, a Nereid riding a hippocampus carries another present.

Altar of Domitius Ahenobarb. Late second century BCE.

Wedding of Neptune and Amphitrite.

Tomb of Marcus Vergilius Eurysaces the Baker

Patronage of public sculpture was not limited to the ruling classes during the Republic. The tomb of Marcus Vergilius Eurysaces the Baker (c. 50-20 BCE) is one of the largest and best-preserved freedman funerary monuments in Rome. Its sculpted frieze is a classic example of the "plebeian style" in Roman sculpture. The deceased built the tomb for himself and perhaps his wife Atistia in the final decades of the Republic. While the tomb's inscription lacks an "L" to denote the status of a freedman, the tripartite name of the deceased follows the pattern of names given to and adopted by former slaves.

The tomb, approximately 33 feet tall, commemorates the deceased and his profession. It three main components are a frieze at the top and cylindrical niches (probably symbolic of a kneading machine or grain measuring vessels) below it. The surviving text of the inscription translates as "This is the monument of Marcus Vergilius Eurysaces, baker, contractor, public servant." The frieze represents various stages in the baking of bread in continuous narration. Although time-worn, the naturalistic depiction of human and animal bodies in a variety of poses is still evident. This record of each stage in a mundane process demonstrates a sense of pride the deceased must have had in his profession. Because the wearing of togas was not conducive to manual labor, the simple clothing on the figures marks them as plebeians, or commoners.

Tomb of Marcus Vergilius Eurysaces the Baker. c. 50-20 BCE.

Surviving south frieze.

Portraiture

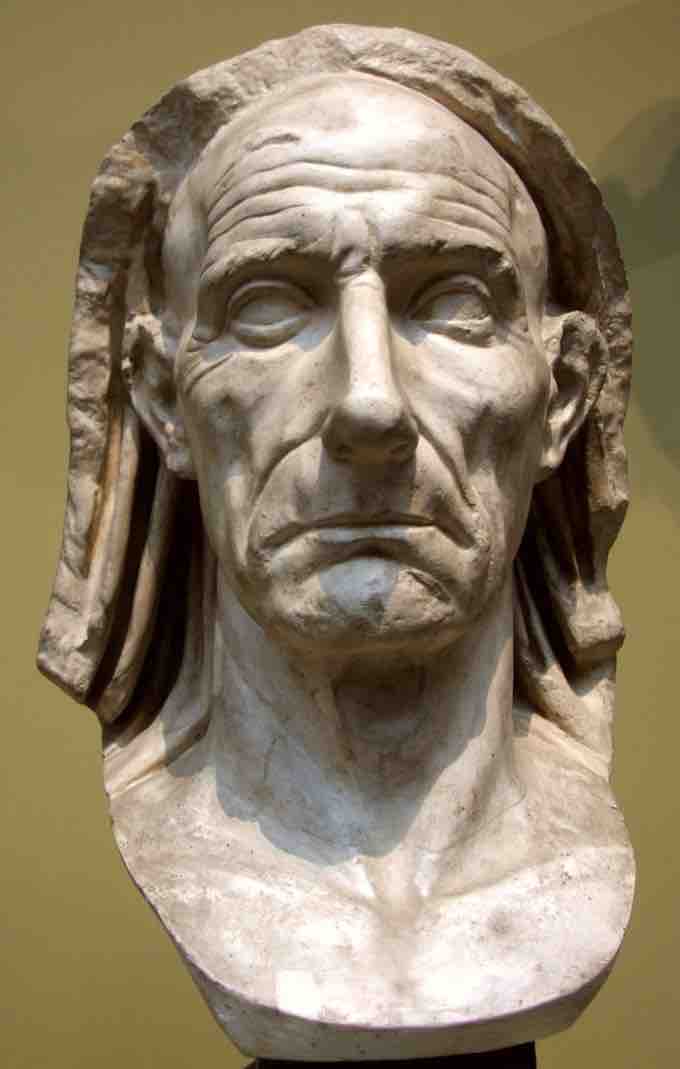

Roman portraiture during the Republic is identified by its considerable realism, known as veristic portraiture. Verism refers to a hyper-realistic portrayal of the subject's facial characteristics. The style originated from Hellenistic Greece; however, its use in the Roman Republic is due to Roman values, customs, and political life. As with other forms of Roman art, portraiture borrowed certain details from Greek art but adapted these to their own needs. Veristic images often show their male subjects with receding hairlines, deep winkles, and even with warts. While the faces of the portraits often display incredible detail and likeness, the subjects' bodies are idealized and do not correspond to the age shown in the face.

Portrait of a Roman General. Sanctuary of Hercules, Tivoli, Italy. c. 75-50 BCE. Marble.

When created as full-length sculptures, the veristic portrait busts appear to have been paired with idealized (mass-produced?) bodies that create a sense of disunity.

Bust of an Old Man.

Veristic portraiture of an Old Man. Verism refers to a hyper-realistic portrayal of the subject's facial characteristics.

The popularity and usefulness of verism appears to derive from the need to have a recognizable image. Veristic portrait busts provided a means of reminding people of distinguished ancestors or of displaying one's power, wisdom, experience, and authority. Statues were often erected of generals and elected officials in public forums—a veristic image ensured that a passerby would recognize the person when they actually saw them.

The Late Republic

The use of veristic portraiture began to diminish in the first century BCE. During this time, civil wars threatened the empire, and individual men began to gain more power. The portraits of Pompey the Great and Julius Caesar, two political rivals who were also the most powerful generals in the Republic, began to change the style of the portraits and their use. The portraits of Pompey are not fully idealized, but nor were they created in the same veristic style of Republican senators. Pompey borrowed a specific parting and curl of his hair from Alexander the Great. This similarity served to link Pompey visually with likeness of Alexander and to remind people that he possessed similar characteristics and qualities.

Marble bust of Pompey the Great.

Portraits of Pompey combine a degree of verism with an idealized hairstyle reminiscent of Alexander the Great.

The portraits of Julius Caesar are more veristic than those of Pompey. Despite staying closer to stylistic convention, Caesar was the first man to mint coins with his own likeness printed on them. In the decades prior to this, it had become increasingly common to place an illustrious ancestor on a coin, but putting a living person--especially oneself--on a coin departed from Roman propriety. By circulating coins issued with his image, Caesar directly showed the people that they were indebted to him for their own prosperity and therefore should support his political pursuits.

Julius Caesar Portrait

Portrait of Julius Caesar on a denarius. On the reverse side stands Venus Victix holding a winged Victory.

Death Masks

The creation and use of death masks demonstrate Romans' veneration of their ancestors. These masks were created from molds taken of a person at the time of his or her death. Made of wax, bronze, marble, and terra cotta, death masks were kept by families and displayed in the atrium of their homes. Visitors and clients who entered the home would have been reminded of the family's ancestry and the honorable qualities of their ancestors. Such displays served to bolster the reputation and credibility of the family. Death masks were also worn and paraded through the streets during funeral procession. Again, this served not only a memorial for the dead, but also to link the living members of a family to their illustrious ancestors in the eyes of the spectator.