Triptych

Triptychs are a type of panel painting or relief carvings for devotional objects that are created on three panels. The panels could also be divided in two, known as diptychs, or sometimes had more than three panels, known as a polyptych. The use of triptychs began in the Byzantine period, and they were originally made to be small and portable. Later during the Gothic period, multi-panel devotional paintings were enlarged as altarpieces. However, the small, portable triptychs of the Byzantine period were used as personal objects of worship. They were designed to guide their owner in prayer and direct their thoughts towards Christ.

The triptych was designed with one central panel and two wings that folded over the main image and allowed the object to be portable, when closed, and to stand, when the wings were open. The wings are typically carved with portrayals of saints, while the main image often depicted Christ, although the imagery varied. The Harbaville Triptych depicts a scene of Deesis with Christ as the Pantokrator, while the Borradaile Triptych depicts an image of the Crucifixion.

Harbaville Triptych

The Harbaville Triptych is an early example from the mid-tenth century of the new ivory triptychs that replaced diptychs during the Middle Byzantine period. The main scene depicts the figures of Christ Pantokrator flanked by John the Baptist and the Virgin Mary, in a supplication scene known as a Deesis. John the Baptist and the Virgin Mary are depicted as intercessors, praying on behalf of the triptych's owner to Christ. On the register below them are the apostles James, John, Peter, Paul, and Andrew. The two side panels depict two registers with two characters each, all of which are identifiable saints.

Harbaville Triptych

Deesis with Saints. Ivory. c. 950.

The figures are carved in a recognizably Byzantine style. Their bodies are elongated and narrow, and they seem to float or hover just above the ground instead of stand with weight. This illusion is furthered by the fact that nearly each character stands on a small platform. The saints are elegantly draped, and their bodies are distinguished by the folds of their drapery and not any type of modeling. The figures' facial expressions are solemn, and their facial features are deeply carved. The saints each face outward, except for John the Baptist and the Virgin Mary, who are each slightly turned and bowing to an enthroned Christ. Christ sits on an elaborate throne as the Pantokrator, with a book of Gospels in one arm and his hand gesturing in a motion of blessing.

Borradaile Triptych

The Borradaile Triptych's main image depicts the Crucifixion of Christ instead of a Deesis. The central image takes up the entirety of the main frame and the two wings are divided into three registers. The figures on the wings are images of saints, similar to the Harbaville Triptych. The central scene is dominated by the image of Christ on the cross. Two angels flank him above his arms. Below are the figures of the Virgin Mary and St. John. St. John gestures and averts his eyes, while Mary lifts a veil to her face, which bears a distraught expression.

Borradaile Triptych

Central panel carved with the Crucifixion, the Virgin and St. John, and above, the half-length figures of the archangels Michael and Gabriel; on the left leaf, from top to bottom: St. Kyros; St. George and St. Theodore Stratilates; St. Menas and St. Prokopios; on the right leaf: St John; St. Eustathius and St Clement of Ankyra; St Stephen and St Kyrion. On the reverse are two inscribed crosses and roundels containing busts of Saints Joachim and Anna in the centers, with Saints Basil and Barbara, and John the Persian and Thekla at the terminus. Ivory. c. 10th century.

The figures, like those of the Harbaville Triptych, are elongated, although less narrow and more rigid. They also are less deeply carved and, because of this appear, more insubstantial. Except for Christ's upper body, which is unclothed, the bodies of the figures are defined by their rigid drapery. The saints stand in straight, upright positions that further provide a sense of solemnity to the scene. Christ is seen on the cross in a stance that focuses on his divine qualities and not his human suffering. The only emotion from the scene derives from his mother, the Virgin Mary, who stands weeping beneath him.

Reliquaries

A reliquary is a protective container used for the storage and display of sacred objects called relics. Relics were a part of the body of a dead saint that was preserved for veneration. Some relics are believed to be endowed with miraculous powers, and other relics have come to play key roles in certain church festivals. The veneration of relics and use of reliquaries became popular during the Byzantine period when the bodies of saints were often moved and divided between Churches. While many relics were honored and venerated, the church never considered this form of devotion as a form of worship, which was an act reserved for God.

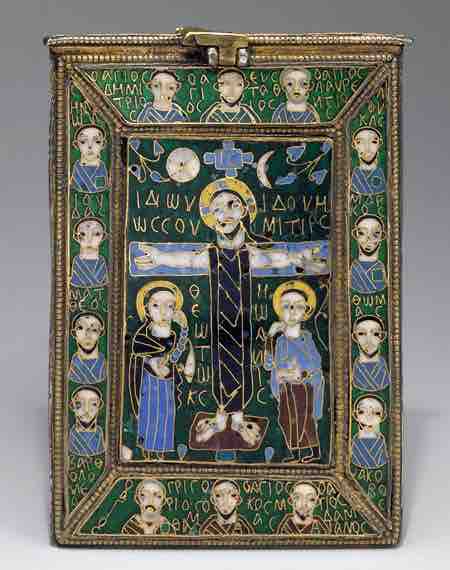

Reliquaries take many forms and shapes and are made out of a variety of materials. However, many reliquaries were made from or decorated with expensive material, such as gold and precious stones. A reliquary from the early ninth century depicts a scene of the Crucifixion with fourteen saints around the border. The reliquary is very small and probably contained a piece of the True Cross, the cross on which Christ was crucified. This reliquary is made from cloisonné, a metalworking technique in which metal was soldered into compartments and was then filled with enamel, glass, gems, or other materials. This reliquary is made with green, white, blue, and red enamel and gold and is only four inches high by nearly three inches wide.

Reliquary of the True Cross

This reliquary depicts a scene of the Crucifixion with fourteen saints around the border. The reliquary is very small and probably contained a piece of the True Cross, the cross on which Christ was crucified.

Psalters

Like triptychs, psalters were small, private objects used for private devotion and worship. A psalter is a book containing the Book of Psalms and other liturgical material such as calendars. They were often commissioned and were richly decorated and illuminated. The surviving psalters contain many fine examples of painting styles and techniques from the Middle Byzantine period.

The Paris Psalter is a mid-tenth century manuscript with fourteen full-page miniature paintings, created in a classical style. As with most art produced under the Macedonian Dynasty, the figures and subject matter were influenced by a revived interest in classical culture. The figures painted in these scenes have bodies with mass and drapery that conforms, not shapes, their bodies. The image depicts David, a psalmist, in an idyllic country setting outside a city (seen in the distance) composing psalms on his harp. He sits with a sheep, goats, dogs, and an angel, representing Melody, while a personification of Echo peers around a column. A male figure, representing the mountain of Bethlehem, lounges on the ground. The image is reminiscent of Greco-Roman wall painting of the musician Orpheus charming people and animals with his music. While the figures appear modeled and are reminiscent of classical art, the psalter has a Byzantine style to it. The clothing is still rendered with bright, contrasting colors and the folds of the drapery are stylized and dark. The slightly skewed perspective given to the vase on top the column and the city in the background are additional elements that provide the scene a Byzantine artistic style.

Paris Psalter

David composing on his harp.

Icons

Icons remained popular devotional objects during the Byzantine period. These objects, which varied in size, depicted the image of a saint, or sacred person such as Christ or Mary, that was considered sacred and was venerated. The images were often painted panels and the display of icons surged following the end of Iconoclasm in the ninth century. Many icons, once reaching this status, would be furthered objectified and protected through the addition of custom gilded frames or gold or silver cases that covered the entirety of the image except for the face of the subject. Other icons, such as a ninth-century depiction of the Crucifixion, contained imagery on both sides.

Double-sided icon with the Crucifixion and the Virgin Hodegitria

Original painting: ninth century. Additional details added in thirteenth century.