The First and Second Iconoclasms

Broadly defined, iconoclasm is defined as the destruction of images. In Christianity, iconoclasm has generally been motivated by people who adopt a literal interpretation of the Ten Commandments, which forbid the making and worshipping of graven images. The period after the reign of Justinian I (527–565) witnessed a significant increase in the use and veneration of images, which helped to trigger a religious and political crisis in the empire. As a result, aniconic sentiment grew, culminating in two periods of iconoclasm -- the First Iconoclasm (726-87) and the Second Iconoclasm (814-42) -- which brought the Early Byzantine period to an end.

Byzantine Iconoclasm constituted a ban on religious images by Emperor Leo III and continued under his successors. It was accompanied by widespread destruction of images and persecution of supporters of the veneration of images. The goal of the iconoclasts was to restore the church to the strict opposition to images in worship that they believed characterized at the least some parts of the early church.

The Feast of Orthodoxy

After the death of the last Iconoclast emperor Theophilos, his young son Michael III, with his mother the regent Theodora and Patriarch Methodios, summoned the Synod of Constantinople in 843 to bring peace to the Church. At the end of the first session, on the first day of Lent, all made a triumphal procession from the Church of Blachernae to Hagia Sophia, restoring the icons to the church in an event called the Feast of Orthodoxy. Imagery, it was decided, is an integral part of faith and devotion, making present to the believer the person or event depicted on them. However, the Orthodox makes a clear doctrinal distinction between the veneration paid to icons and the worship which is due to God alone.

Since Iconoclasm was the last of the great Christological controversies to trouble the Church, its defeat is considered to be the final triumph of the Church over heresy. When the Iconoclasm controversy came to an end in 843, Byzantine religious art underwent a renewal. A series of naturalistic innovations can be seen in examples from the Hagia Sophia, the monastery of Hosios Loukas, and Saint Mark's Basilica. This revival of a classical style of art was partly due to a renewed interest in classical culture, which accompanied a period of military successes, during the Macedonian Renaissance (867-1056).

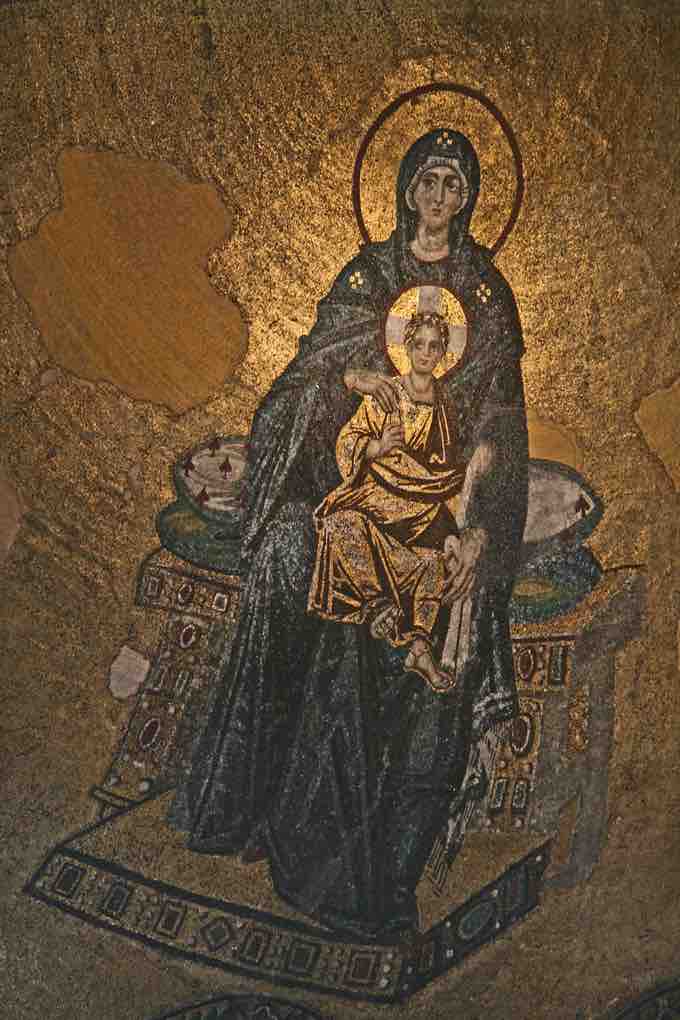

Theotokos Mosaic at the Hagia Sophia

The Hagia Sophia is a former Greek Orthodox patriarchal basilica (church), constructed from 537 until 1453. A combination of a centrally-planned and basilican building, it is considered the epitome of Byzantine architecture. After the end of iconoclasm, a new mosaic was dedicated in the Hagia Sophia under the Patriarch Photius and the Macedonian emperors Michael III and Basil I. The mosaic is located in the apse over the main alter and depicts the Theotokos, or the Mother of God. The image, in which the Virgin Mary sits on a throne with the Christ child on her lap, is believed to be a reconstruction of a sixth-century mosaic that was destroyed during the Iconoclasm. An inscription reads: "The images which the impostors had cast down here, pious emperors (Michael and Basil) have again set up." This inscription refers to the recent past and the renewal of Byzantine art under the Macedonian emperors.

Theokotos and Child, Hagia Sophia, Constantinople (Istanbul), Turkey.

This image, in which the Virgin Mary sits on a throne with the Christ Child, is believed to be a reconstruction of a sixth-century mosaic that was destroyed during the Iconoclasm.

The image of the Virgin and Child is a common Christian image, and the mosaic depicts Byzantine innovations and the standard style of the period. The Virgin's lap is large. Christ sits nestled between her two legs. The figures' faces are depicted with gradual shading and modeling that provides a sense of realism which contradicts the schematic folding of their drapery. Thick, harsh folds delineated by contrasting colors, the Virgin in blue and Christ in gold, define their drapery. The two frontal figures sit on an embellished gold throne that is tilted to imply perspective. This attempt is a new addition in Byzantine art during this period. The space given to the chair contradicts the frontality of the figures, but it provides a sense of realism previously unseen in Byzantine mosaics.

Hosios Loukas, Greece

The monastery of Hosios Loukas (St. Luke) in Greece was founded in the early tenth century to host the relics of St. Luke. Located on the slope of Mount Helicon, the monastery is known for its two churches, the Church of the Theotokos (tenth century) and the main building called the Katholikon (eleventh century). The churches were decorated in mosaics, frescoes, and marble revetment. The two churches are connected together by the narthex of the Theotokos and an arm of the Katholikon. The churches demonstrate two different styles of architecture.

Plan of Hosios Loukas

Top (#1 on diagram): Plan of Church of the Theotokos; Bottom (#2): Plan of Katholikon.

The Church of the Theokotos represents a Greek cross-plan style church. It has a large central dome that rests on a series of pendentives. The Katholikon is also a Greek cross-plan style church but instead of the dome resting on pendentives, the dome of the Katholikon rests on squinches, which create an octagonal transition between the square plan of the church and the circular plan of the dome. The difference in style between the pendentives and the squinches allow for different relationships between the architecture and the decoration and different play of light and darkness in the shapes the squinches provided.

Hosios Loukas Katholikon, Greece.

Unlike the Church of the Theokotos, the dome of the Katholikon rests on squinches.

The mosaics found in the Katholikon were created in an early Byzantine style commonly seen in the centuries before Iconoclasm. The scenes depicted are flat with little architecture or props to provide a setting. Instead, the background is covered in brilliant gold mosaics. The figures in the scenes, such as those seen in the apse mosaic of Christ washing the feet of his disciples, are depicted with naturalistic faces that are modeled and with long, narrow noses and small mouths. The clothing of the figures is represented through schematic folds and contrasting colors. While the folds of the drapery represent a body underneath, there appears to be no actual mass to the body. These characteristics seen in Byzantine mosaics began to change in the following century, partially through the addition of perspective in the Theokotos of the Hagia Sophia.

Christ Washing the Feet of His Disciples, Hosios Loukas, Greece.

The figures in these scenes are depicted with naturalistic faces that are modeled and with long, narrow noses and small mouths.

Saint Mark's Basilica, Venice

Saint Mark's Basilica in Venice, Italy, was first built in the ninth century and rebuilt in the eleventh century in its current form following a fire. The basilica is a grand building, built next to the Doge's Palace. It initially functioned as the doge's private chapel, then a state church, and in 1806 became the city's cathedral. The basilica houses the remains of Saint Mark, which the Venetians looted from Alexandria in 828 (prompting the building of the basilica).

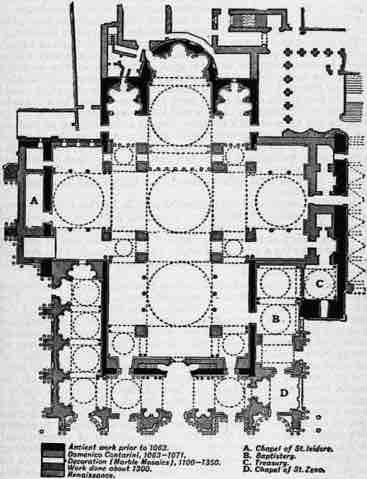

Saint Mark's Basilica was built in the Byzantine style of a Greek-cross plan. Each arm is divided into three naves and is topped by a dome. At the crossing is a large central dome. The main apse is flanked by two smaller chapels. The narthex of the basilica is U-shaped and wraps around the western transept. It is decorated with scenes from the lives of Old Testament prophets.

Plan of St. Mark's Basilica

The circles mark the location of each dome.

The entirety of the basilica is richly decorated. The floor is covered in geometric patterns and designs using Roman decorated techniques known as opus sectile and opus tessellatum. The lower walls and pillars are covered in marble polychromatic panels, and the upper walls and the domes are decorated with twelfth- and thirteenth-century mosaics. The central dome depicts an image of Christ Pantocrator, and the overall decorative program depicts scenes from the life of Christ and images of salvation from both the Old and New Testament.

Interior of St. Mark's Basilic, Venice, Italy

A view of the interior of St. Mark's Basilica from the clerestory-level walkway shows its richly decorated mosaics and marble polychrome panels.