Timber Architecture

Background

Timber architecture can be used to describe a period of medieval art in which two distinctive wood building traditions found their confluence in Norwegian architecture. One was the practice of log building with horizontal logs notched at the corners, a technique thought to have been imported east of Scandinavia. The other influence was the stave building tradition, which possibly evolved from improvements on the prehistoric long houses that had roof-bearing posts dug into the ground.

Although scant evidence exists, archaeological findings of actual buildings from the earliest permanent structures, the discovery of Viking ships (i.e. the Oseberg), and stave churches suggest a significant mastery of woodworking and engineering in Viking culture. Not counting the 28 remaining stave churches, at least 250 wooden houses predating the Black Death of 1350 are preserved more or less intact in Norway. Most of these are long houses, some with added stave-built galleries or porches. As political power in Norway was consolidated and had to contend with external threats, larger and more durable structures than the timber examples were built in accordance with military technology at the time. Hence, fortresses, bridges, and ultimately churches and manors were built with stone and masonry.

Long Houses

Very little archaeological evidence of actual buildings from the earliest permanent structures in the Viking era have survived. However, in the Lofoten archipelago in Northern Norway, a Viking chieftain's holding has been reconstructed at the Lofotr Viking Museum. In 1983, archaeologists uncovered the Chieftain House at Borg, a large Viking Era building believed to have been already established around the year 500 CE. Excavations later in the 1980s revealed the largest building ever to be found from the Viking period in Norway. The foundation of the Chieftain House at Borg measured 272 feet long and 30 feet high. After the excavation ended, the remains of what had once been the long house remained visible.

Viking long house

Reconstructed long house in the Vikingmuseum in Borg, Vestvågøy/Lofoten, Norway.

Typically load-bearing with post-and-lintel entrances, long houses had sharply pitched roofs that bore a curve similar to that of a ship. In fact, the roofs of many reconstructed long houses resemble inverted boats that have been placed atop the exterior walls. This shape was likely due to the climate, as pitched roofs allow snow to fall to the ground without causing the roof to collapse. Also known as mead halls, long houses typically housed the high-ranking members of Viking society, particularly royalty and aristocracy. From around the year 500 up until the Christianization of Scandinavia (by the thirteenth century), these large halls were vital parts of the political center. They were later superseded by medieval banquet halls.

Stave Churches

The most commonly cited examples of timber architecture are the Norwegian stave churches. Until the beginning of the nineteenth century, as many as 150 stave churches still existed. Many were destroyed as part of a religious movement that favored simple, puritan lines, and today only 28 remain (although a large number were documented and recorded by measured drawings before they were demolished).

A stave church is a medieval wooden church with a post and beam construction related to timber framing. The wall frames are filled with vertical planks. The load-bearing posts (stafr in Old Norse, stav in Norwegian) have lent their name to the building technique. The stave churches owe their longevity to architectural innovations that protected these large, complex wooden structures against water rot, precipitation, wind, and extreme temperatures. Most important was the introduction of massive sills underneath the staves (posts) to prevent them from rotting. Over the two centuries of stave church construction, this building type evolved to an advanced art and science.

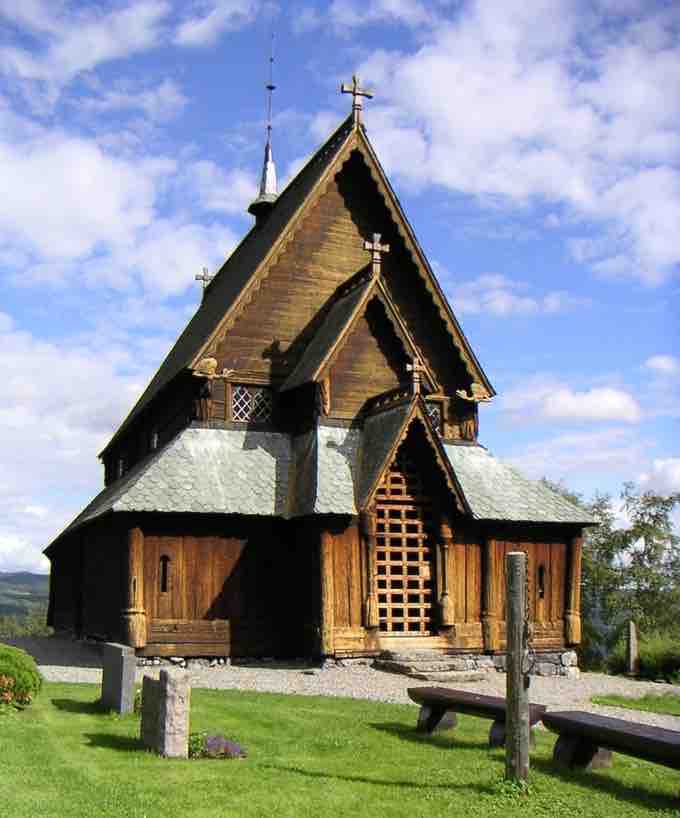

Stave Church

Example of a Norwegian wooden stave church: Stave church in Lom.

Forms of Church Construction

Archaeological excavations have shown that stave churches descend from palisade constructions and later churches with earth-bound posts. Similar palisade constructions are known from the buildings of the Viking era. Logs were split in two halves, rammed into the ground, and given a roof. This was a simple form of construction but very strong. The wall could last for decades if set in gravel—even centuries. Remains of buildings of this type are found over much of Europe. It is now common to group the churches into two categories. Type A had no free-standing posts and a single nave, as seen in the Renli Stave Church. Type B had a raised roof and free-standing internal posts, as in the Lomen Stave Church.

Type A Reinli Stave Church

Reinli stave church with the old pillory and a single nave: Sør-Aurdal.

Type B Lomen Stave Church Interior

Interior from Lomen stave church depicting a raised roof and cross braces between upper and lower string beams and posts. Intermediate posts have been omitted.

Type B churches were often further divided into two subgroups. The first was the Kaupanger group that had a complete arcade row of posts and intermediate posts along the sides and details that mimic stone capitals. These churches gave an impression of a basilica. The other subgroup was the Borgund group. These churches had cross braces joining upper and lower string beams and posts that formed a very rigid interconnection, resembling the triforium of stone basilicas. Many stave churches had or still have outer galleries running around the entire perimeter, loosely connected to the plank walls. They probably served to protect the church from the harsh climate.

After the Protestant Reformation, no stave churches were built. Instead, new churches were mainly composed of stone or horizontal log buildings with notched corners. Most old stave churches disappeared because of redundancy, neglect, deterioration, or because they were too small to accommodate larger congregations and too impractical according to newer architectural standards.

Ornamentation of Stave Churches

Even though the wooden churches had structural differences, they give a recognizable general impression. Formal differences might hide common features of their planning, while apparently similar buildings might have structural elements that are organized completely differently. Despite this, certain basic principles must have been common to all types of building.

Basic geometric figures, simple numbers, one or just a few length units and simple ratios, and perhaps also proportions were among the theoretical aids all builders inherited. The specialist knew a particular type of building so well that he could systematize its elements in a slightly different way from previous building designs, thus carrying developments a stage further. Ornamentation included intricate interlace patterns, stylized human figures, and mythological animals.

Hedal stave church portal

Drawing by G. A. Bull of the main portal in Hedalen stave church (c. 1853).