Financial markets come in a variety of flavors to accommodate the wide array of financial instruments or securities that have been found beneficial to both borrowers and lenders over the years. Primary markets are where newly created (issued) instruments are sold for the first time. Most securities are negotiable. In other words, they can be sold to other investors at will in what are called secondary markets. Stock exchanges, or secondary markets for ownership stakes in corporations called stocks (aka shares or equities), are the most well-known type, but there are also secondary markets for debt, including bonds (evidences of sums owed, IOUs), mortgages, and derivativesDerivatives are complex financial instruments, the prices of which are based on the prices of underlying assets, variables, or indices. Some investors use them to hedge (reduce) risks, while others (speculators) use them to increase risks. and other instruments. Not all secondary markets are organized as exchanges, centralized locations, like the New York Stock Exchange or the Chicago Board of Trade, for the sale of securities. Some are over-the-counter (OTC) markets run by dealersBusinesses that buy and sell securities continuously at bid and ask prices, profiting from the difference or spread between the two prices. connected via various telecom devices (first by post and semaphore [flag signals], then by telegraph, then telephone, and now computer). Completely electronic markets have gained much ground in recent years and now dominate most trading.“Stock Exchanges: The Battle of the Bourses,” The Economist (31 May 2008), 77–79.

Money markets are used to trade instruments with less than a year to maturity (repayment of principal). Examples include the markets for T-bills (Treasury bills or short-term government bonds), commercial paper (short-term corporate bonds), banker’s acceptances (guaranteed bank funds, like a cashier’s check), negotiable certificates of deposit (large-denomination negotiable CDs, called NCDs), Fed funds (overnight loans of reserves between banks), call loans (overnight loans on the collateral of stock), repurchase agreements (short-term loans on the collateral of T-bills), and foreign exchange (currencies of other countries).

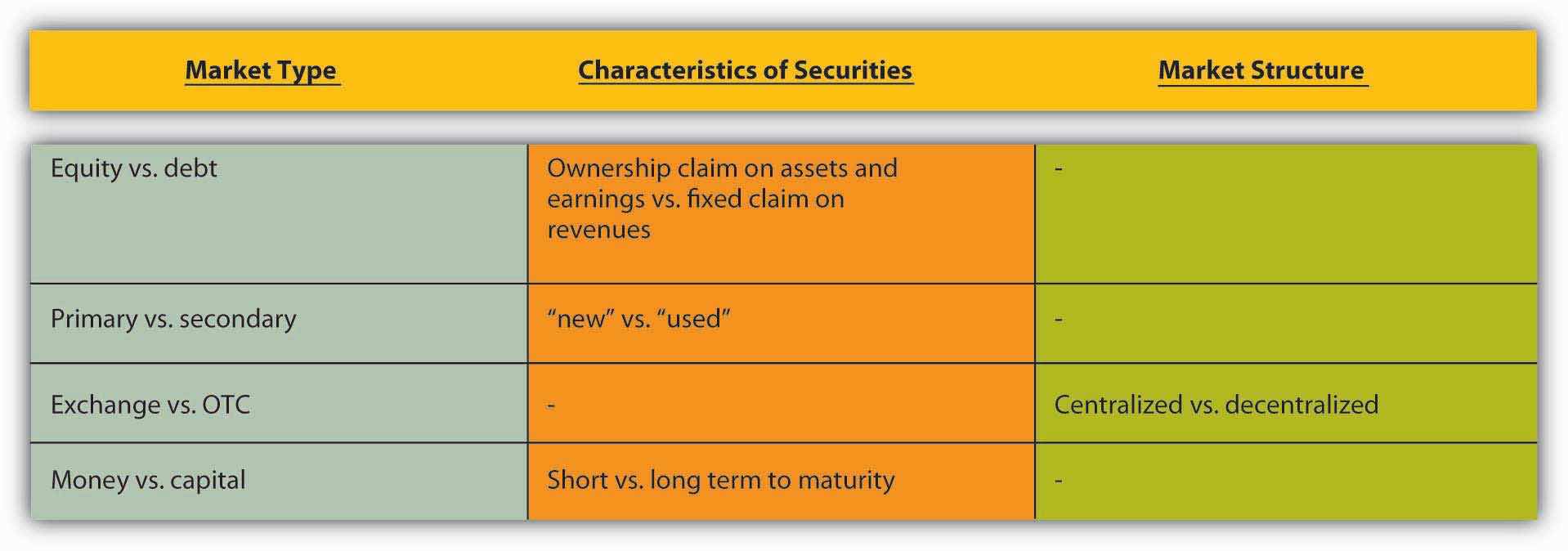

Securities with a year or more to maturity trade in capital markets. Some capital market instruments, called perpetuities, never mature or fall due. Equities (ownership claims on the assets and income of corporations) and perpetual interest-only loans are prime examples. (Some interest-only loans mature in fifteen or thirty years with a so-called balloon payment, in which the principal falls due all at once at the end of the loan.) Most capital market instruments, including mortgages (loans on real estate collateralProperty pledged as security for the repayment of a loan.), corporate bonds, government bonds, and commercial and consumer loans, have fixed maturities ranging from a year to several hundred years, though most capital market instruments issued today have maturities of thirty years or less. Figure 2.4 "Types of financial markets" briefly summarizes the differences between various types of financial markets.

Figure 2.4 Types of financial markets

Derivatives contracts trade in a third type of financial market. Derivatives allow investors to spread and share a wide variety of risks, from changes in interest rates and stock market indicesquote.yahoo.com/m1?u to undesirable weather conditionswww.cme.com/trading/prd/weather/index.html (too sunny for farmers, too rainy for amusement parks, too cold for orange growers, too hot for ski resorts). Financial derivatives are in some ways even more complicated than the derivatives in calculus, so they are discussed in detail in a separate chapter.

Some call financial markets “direct finance,” though most admit the term is a misnomer because the functioning of the markets is usually aided by one or more market facilitators, including brokers, dealers, brokerages, and investment banks. Brokers facilitate secondary markets by linking sellers to buyers of securities in exchange for a fee or a commission, a percentage of the sale price. Dealers “make a market” by continuously buying and selling securities, profiting from the spread, or the difference between the sale and purchase prices. (For example, a dealer might buy a certain type of bond at, say, $99 and resell it at $99.125, ten thousand times a day.) Brokerages engage in both brokering and dealing and usually also provide their clients with advice and information. Investment banks facilitate primary markets by underwriting (buying for resale to investors) stock and bond offerings, including initial public offerings (IPOs) of stocks, and by arranging direct placementA sale of financial securities, usually bonds, via direct negotiations with buyers, usually large institutional investors like insurance and investment companies. of bonds. Sometimes investment banks act merely as brokers, introducing securities issuers to investors, usually institutional investors like the financial intermediaries discussed below. Sometimes they act as dealers, buying the securities themselves for later (hopefully soon!) resale to investors. And sometimes they provide advice, usually regarding mergerA merger occurs when two or more extant business firms combine into one through a pooling of interests or through purchase. and acquisitionWhen one company takes a controlling interest in another; when one business buys another.. Investment banks took a beating during the financial crisis that began in 2007. Most of the major ones went bankrupt or merged with large commercial banks. Early reports of the death of investment banking turned out to be premature, but the sector is depressed at present; two large ones and numerous small ones, niche players called boutiques, remain.“American Finance: And Then There Were None. What the death of the investment bank means for Wall Street,” The Economist (27 September 2008), 85–86.

In eighteenth-century Pennsylvania and Maryland, people could buy real estate, especially in urban areas, on so-called ground rent, in which they obtained clear title and ownership of the land (and any buildings or other improvements on it) in exchange for the promise to pay some percentage (usually 6) of the purchase price forever. What portion of the financial system did ground rents (some of which are still being paid) inhabit? How else might ground rents be described?

Ground rents were a form of market or direct finance. They were financial instruments or, more specifically, perpetual mortgages akin to interest-only loans.

Financial markets are increasingly international in scope. Integration of transatlantic financial markets began early in the nineteenth century and accelerated after the mid-nineteenth-century introduction of the transoceanic telegraph systems. The process reversed early in the twentieth century due to both world wars and the Cold War; the demise of the gold standard;John H. Wood, “The Demise of the Gold Standard,” Economic Perspectives (Nov. 1981): 13-23. and the creation of Bretton Woods, a system of fixed exchange rates, discretionary monetary policy, and capital immobility.economics.about.com/od/foreigntrade/a/bretton_woods.htm (We’ll explore these topics and a related matter, the so-called trilemma, or impossible trinity, in another chapter.) With the end of the Bretton Woods arrangement in the early 1970s and the Cold War in the late 1980s/early 1990s, financial globalization reversed course once again. Today, governments, corporations, and other securities issuers (borrowers) can sell bonds, called foreign bonds, in a foreign country denominated in that foreign country’s currency. (For example, the Mexican government can sell dollar-denominated bonds in U.S. markets.) Issuers can also sell Eurobonds or Eurocurrencies, bonds issued (created and sold) in foreign countries but denominated in the home country’s currency. (For example, U.S. companies can sell dollar-denominated bonds in London and U.S. dollars can be deposited in non-U.S. banks. Note that the term Euro has nothing to do with the euro, the currency of the European Union, but rather means “outside.” A Euro loan, therefore, could be a loan denominated in euro but made in London, New York, Tokyo, or Perth.) It is now also quite easy to invest in foreign stock exchanges,www.foreign-trade.com/resources/financel.htm many of which have grown in size and importance in the last few years, even if they struggled through the panic of 2008.

To purchase the Louisiana Territory from Napoleon in 1803, the U.S. government sold long-term, dollar-denominated bonds in Europe. What portion of the financial system did those bonds inhabit? Be as specific as possible.

Those government bonds were Eurobonds because the U.S. government issued them overseas but denominated them in U.S. dollars.