This is “International Monetary Regimes”, chapter 19 from the book Finance, Banking, and Money (v. 1.0).

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. You may also download a PDF copy of this book (8 MB) or just this chapter (334 KB), suitable for printing or most e-readers, or a .zip file containing this book's HTML files (for use in a web browser offline).

Chapter 19 International Monetary Regimes

Chapter Objectives

By the end of this chapter, students should be able to:

- Define the impossible trinity, or trilemma, and explain its importance.

- Identify the four major types of international monetary regimes and describe how they differ.

- Explain how central banks manage the foreign exchange (FX) rate.

- Explain the benefits of fixing the FX rate, or keeping it within a narrow band.

- Explain the costs of fixing the FX rate, or keeping it in a narrow band.

19.1 The Trilemma, or Impossible Trinity

Learning Objectives

- What is the impossible trinity, or trilemma, and why is it important?

- What are the four major types of international monetary regimes and how do they differ?

The foreign exchange (forex, or FXThe price of one currency in terms of another.) market described in Chapter 18 "Foreign Exchange" is called the free floating regime because monetary authorities allow world markets (via interest rates, and expectations about relative price, productivity, and trade levels) to determine the prices of different currencies in terms of one another. The free float, as we learned, was characterized by tremendous exchange rate volatility and unfettered international capital mobility. As we learned in Chapter 13 "Central Bank Form and Function" through Chapter 17 "Monetary Policy Targets and Goals", it is also characterized by national central banks with tremendous discretion over domestic monetary policy. The free float is not, however, the only possible international monetary regime. In fact, it has pervaded the world economy only since the early 1970s, and many nations even today do not embrace it. Between World War II and the early 1970s, much of the world (the so-called first, or free, world) was on a managed, fixed-FX regime called the Bretton Woods SystemA system of fixed exchange rates based on gold and the USD used by most of the world’s free (noncommunist) countries in the quarter century after World War II. (BWS). Before that, many nations were on the gold standardA fixed exchange rate regime based on gold. (GS), as summarized in Figure 19.1 "The trilemma, or impossible trinity, of international monetary regimes".

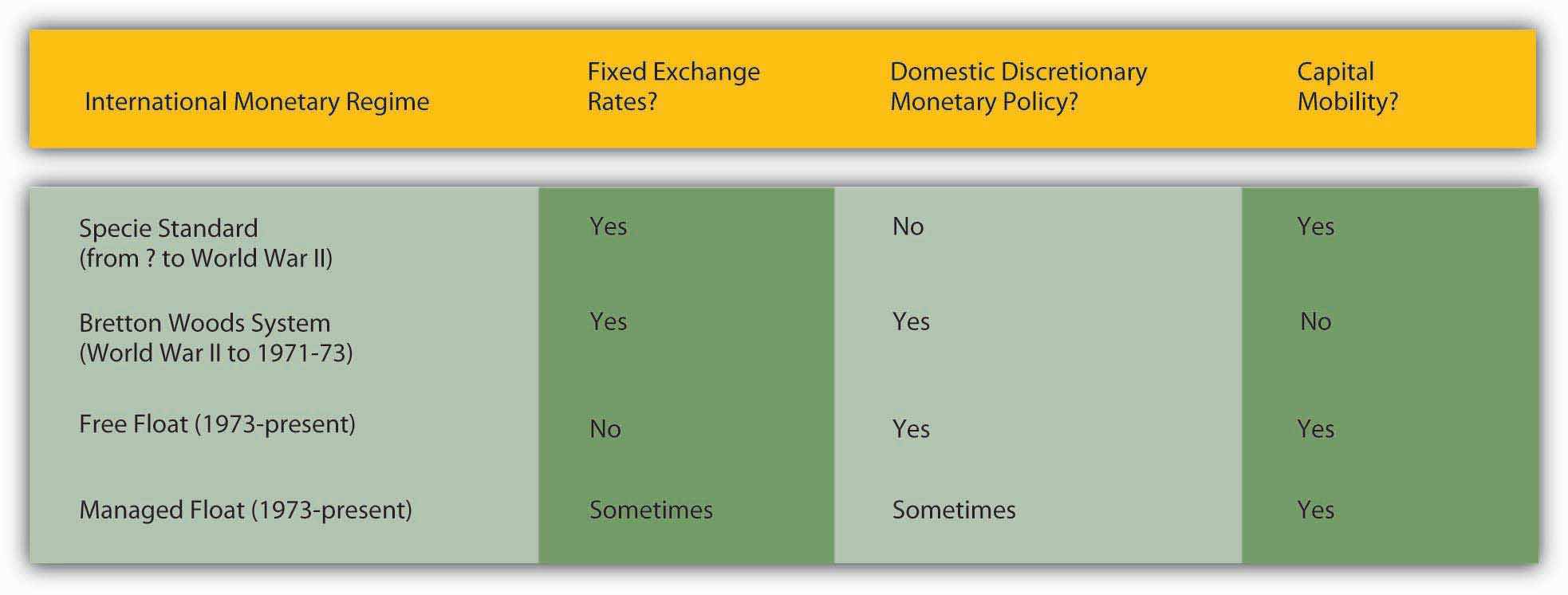

Figure 19.1 The trilemma, or impossible trinity, of international monetary regimes

Note that those were the prevailing regimes. Because nations determine their monetary relationship with the rest of the world individually, some countries have always remained outside the prevailing system, often for strategic reasons. In the nineteenth century, for example, some countries chose a silver rather than a gold standard. Some allowed their currencies to float in wartime. Today, some countries maintain fixed exchange rates (usually against USD) or manage their currencies so their exchange rates stay within a band or range. But just as no country can do away with scarcity or asymmetric information, none can escape the trilemma (a dilemma with three components), also known as the impossible trinity.

Figure 19.2 Strengths and weaknesses of international monetary regimes

As Figure 19.1 "The trilemma, or impossible trinity, of international monetary regimes" shows, only two of the three holy grails of international monetary policy, fixed exchanged rates, international financial capital mobility, and domestic monetary policy discretion, can be satisfied at once. Countries can adroitly change regimes when it suits them, but they cannot enjoy capital mobility, fixed exchange rates, and discretionary monetary policy all at once. That is because, to maintain a fixed exchange rate, a monetary authority (like a central bank) has to make that rate its sole consideration (thus giving up on domestic goals like inflation or employment/gross domestic product [GDP]), or it has to seal off the nation from the international financial system by cutting off capital flows. Each component of the trilemma comes laden with costs and benefits, so each major international policy regime has strengths and weaknesses, as outlined in Figure 19.2 "Strengths and weaknesses of international monetary regimes".

Stop and Think Box

From 1797 until 1820 or so, Great Britain abandoned the specie standardA fixed exchange rate regime based on specie, i.e., gold and/or silver. it had maintained for as long as anyone could remember and allowed the pound sterling to float quite freely. That was a period of almost nonstop warfare known as the Napoleonic Wars. The United States also abandoned its specie standard from 1775 until 1781, from 1814 until 1817, and from 1862 until essentially 1873. Why?

Those were also periods of warfare and their immediate aftermath in the United States—the Revolution, War of 1812, and Civil War, respectively. Apparently during wartime, both countries found the specie standard costly and preferred instead to float with free mobility of financial capital. That allowed them to borrow abroad while simultaneously gaining discretion over domestic monetary policy, essentially allowing them to fund part of the cost of the wars with a currency tax, which is to say, inflation.

Key Takeaways

- The impossible trinity, or trilemma, is one of those aspects of the nature of things, like scarcity and asymmetric information, that makes life difficult.

- Specifically, the trilemma means that a country can follow only two of three policies at once: international capital mobility, fixed exchange rates, and discretionary domestic monetary policy.

- To keep exchange rates fixed, the central bank must either restrict capital flows or give up its control over the domestic money supply, interest rates, and price level.

- This means that a country must make difficult decisions about which variables it wants to control and which it wants to give up to outside forces.

- The four major types of international monetary regime are specie standard, managed fixed exchange rate, free float, and managed float.

- They differ in their solution, so to speak, of the impossible trinity.

- Specie standards, like the classical GS, maintained fixed exchange rates and allowed the free flow of financial capital internationally, rendering it impossible to alter domestic money supplies, interest rates, or inflation rates.

- Managed fixed exchange rate regimes like BWS allowed central banks discretion and fixed exchange rates at the cost of restricting international capital flows.

- Under a free float, free capital flows are again allowed, as is domestic discretionary monetary policy, but at the expense of the security and stability of fixed exchange rates.

- With a managed float, that same solution prevails until the FX rate moves to the top or bottom of the desired band, at which point the central bank gives up its domestic discretion so it can concentrate on appreciating or depreciating its currency.

19.2 Two Systems of Fixed Exchange Rates

Learning Objective

- What were the two major types of fixed exchange rate regimes and how did they differ?

Under the gold standard, nations defined their respective domestic units of account in terms of so much gold (by weight and fineness or purity) and allowed gold and international checks (known as bills of exchange) to flow between nations unfettered. Thanks to arbitrageurs, the spot exchange rate, the market price of bills of exchange, could not stray very far from the exchange rate implied by the definition of each nation’s unit of account. For example, the United States and Great Britain defined their units of account roughly as follows: 1 oz. gold = $20.00; 1 oz. gold = £4. Thus, the implied exchange rate was roughly $5 = £1 (or £.20 = $1). It was not costless to send gold across the Atlantic, so Americans who had payments to make in Britain were willing to buy sterling-denominated bills of exchange for something more than $5 per pound and Americans who owned sterling bills would accept something less than $5 per pound, as the supply and demand conditions in the sterling bills market dictated. If the dollar depreciated too far, however, people would stop buying bills of exchange and would ship gold to Britain instead. That would decrease the U.S. money supply and appreciate the dollar. If the dollar appreciated too much, people would stop selling bills of exchange and would order gold shipped from Britain instead. That increased the U.S. money supply and depreciated the dollar. The GS system was self-equilibrating, functioning without government intervention (after their initial definition of the domestic unit of account).

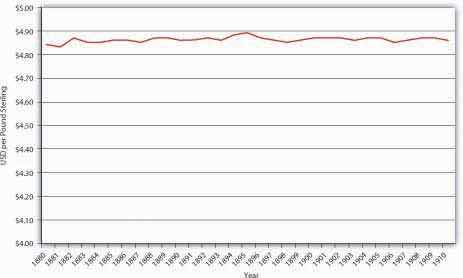

Figure 19.3 Dollar-sterling exchange during the classical gold standard

As noted in Figure 19.2 "Strengths and weaknesses of international monetary regimes" and shown in Figure 19.3 "Dollar-sterling exchange during the classical gold standard", the great strength of the GS was exchange rate stability. One weakness of the system was that the United States had so little control of its domestic monetary policy that it did not need, or indeed have, a central bank. Other GS countries, too, suffered from their inability to adjust to domestic shocks. Another weakness of the GS was the annoying fact that gold supplies were rarely in synch with the world economy, sometimes lagging it, thereby causing deflation, and sometimes exceeding it, hence inducing inflation.

Stop and Think Box

Why did the United States find it prudent to have a central bank (the B.U.S. [1791–1811] and the S.B.U.S. [1816–1836]) during the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries, when it was on a specie standard, but not later in the nineteenth century? (Hint: Transatlantic transportation technology improved dramatically beginning in the 1810s.)

As discussed in earlier chapters, the B.U.S. and S.B.U.S. had some control over the domestic money supply by regulating commercial bank reserves via the alacrity of its note and deposit redemption policy. Although the United States was on a de facto specie standard (legally bimetallic but de facto silver, then gold) at the time, the exchange rate bands were quite wide because transportation costs (insurance, freight, interest lost in transit) were so large compared to later in the century that the U.S. monetary regime was more akin to a modern managed float. In other words, the central bank had discretion to change the money supply and exchange rates within the wide band that the costly state of technology created.

The Bretton Woods System adopted by the first world countries in the final stages of World War II was designed to overcome the flaws of the GS while maintaining the stability of fixed exchange rates. By making the dollar the free world’s reserve currency (basically substituting USD for gold), it ensured a more elastic supply of international reserves and also allowed the United States to earn seigniorage to help offset the costs it incurred fighting World War II, the Korean War, and the cold war. The U.S. government promised to convert USD into gold at a fixed rate ($35 per oz.), essentially rendering the United States the banker to more than half of the world’s economy. The other countries in the system maintained fixed exchange rates with the dollar and allowed for domestic monetary policy discretion, so the BWS had to restrict international capital flows. Little wonder that the period after World War II witnessed a massive shrinkage of the international financial system.

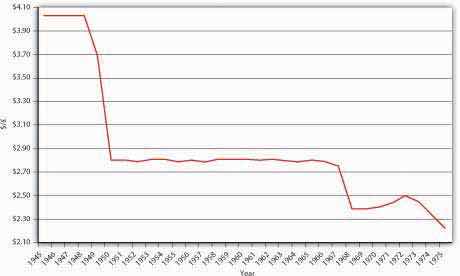

Under the BWS, if a country could no longer defend its fixed rate with the dollar, it was allowed to devalue its currency, or in other words, to set a newer, weaker exchange rate. As Figure 19.4 "Dollar–sterling exchange under BWS" reveals, Great Britain devalued several times, as did other members of the BWS. But what ultimately destroyed the system was the fact that the banker, the United States, kept issuing more USD without increasing its reserve of gold. The international equivalent of a bank run ensued because major countries, led by France, exchanged their USD for gold. Attempts to maintain the BWS in the early 1970s failed. Thereafter, Europe created its own fixed exchange rate system called the exchange rate mechanism (ERM), with the German mark as the reserve currency. That system morphed into the European currency union and adopted a common currency called the euro.

Figure 19.4 Dollar–sterling exchange under BWS

Most countries today allow their currencies to float freely or employ a managed float strategy. With international capital mobility restored in many places after the demise of the BWS, the international financial system has waxed ever stronger since the early 1970s.

Key Takeaways

- The two major types of fixed exchange rate regimes were the gold standard and Bretton Woods.

- The gold standard relied on retail convertibility of gold, while the BWS relied on central bank management where the USD stood as a sort of substitute for gold.

19.3 The Managed or Dirty Float

Learning Objective

- How can central banks manage the FX rate?

The so-called managed float (aka dirty float) is perhaps the most interesting attempt to, if not eliminate the impossible trinity, at least to blunt its most pernicious characteristic, that of locking countries into the disadvantages outlined in Figure 19.2 "Strengths and weaknesses of international monetary regimes". Under a managed float, the central bank allows market forces to determine second-to-second (day-to-day) fluctuations in exchange rates but intervenes if the currency grows too weak or too strong. In other words, it tries to keep the exchange rate range bound. Those ranges or bands can vary in size from very wide to very narrow and can change levels over time.

Central banks intervene in the foreign exchange markets by exchanging international reserves, assets denominated in foreign currencies, gold, and special drawing rights (SDRsLiabilities of the International Monetary Fund (IMF), an institution established as part of the BWS., for domestic currency). Consider the case of Central Bank selling $10 billion of international reserves, thereby soaking up $10 billion of MB (the monetary base, or currency in circulation and/or reserves). The T-account would be:

| Central Bank | |

|---|---|

| Assets | Liabilities |

| International reserves −$10 billion | Currency in circulation or reserves −$10 billion |

If it were to buy $100 million of international reserves, both MB and its holdings of foreign assets would increase:

| Central Bank | |

|---|---|

| Assets | Liabilities |

| International reserves +$100 million | Monetary base +$100 million |

Such transactions are known in the biz as unsterilized foreign exchange interventions and they influence the FX rate via changes in MB. Recall from Chapter 18 "Foreign Exchange" that increasing the money supply (MS) causes the domestic currency to depreciate, while decreasing the MS causes it to appreciate. It does so by influencing both the domestic interest rate (nominal) and expectations about Eef, the future exchange rate, via price level (inflation) expectations. (There is also a direct effect on the MS, but it is too small in most instances to be detectable and so it can be safely ignored. Intuitively, however, increasing the money supply leaves each unit of currency less valuable, while decreasing it renders each unit more valuable.)

Central banks also sometimes engage in so-called sterilized foreign exchange interventions when they offset the purchase or sale of international reserves with a domestic sale or purchase. For example, a central bank might offset or sterilize the purchase of $100 million of international reserves by selling $100 million of domestic government bonds, or vice versa. In terms of a T-account:

| Central Bank | |

|---|---|

| Assets | Liabilities |

| International reserves +$100 million | Government bonds −$100 million |

| Monetary base +$100 million | Monetary base −$100 million |

Because there is no net change in MB, a sterilized intervention should have no long-term impact on the exchange rate. Apparently, central bankers engage in sterilized interventions as a short-term ruse (where central banks are not transparent, considerable asymmetric information exists between them and the markets) or to signal their desire to the market. Neither go very far, so for the most part central banks that wish to manage their nation’s exchange rate must do so via unsterilized interventions, buying international reserves with domestic currency when they want to depreciate the domestic currency, and selling international reserves for domestic currency when they want the domestic currency to appreciate.

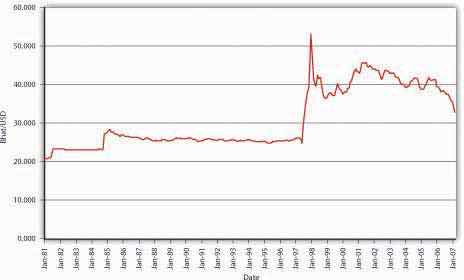

The degree of float management can range from a hard peg, where a country tries to keep its currency fixed to another, so-called anchor currency, to such wide bands that intervention is rarely undertaken. Figure 19.5 "Thai bhat–USD exchange rate, 1981–2007" clearly shows that Thailand used to maintain a hard peg against the dollar but gave it up during the Southeast Asian financial crisis of 1997. That big spike was not pleasant for Thailand, especially for economic agents within it that had debts denominated in foreign currencies, which suddenly became much more difficult to repay. (In June 1997, it took only about 25 baht to purchase a dollar. By the end of that year, it took over 50 baht to do so.) Clearly, a major downside of maintaining a hard peg or even a tight band is that it simply is not always possible for the central bank to maintain or defend the peg or band. It can run out of international reserves in a fruitless attempt to prevent a depreciation (cause an appreciation). Or maintenance of the peg might require increasing or decreasing the MB counter to the needs of the domestic economy.

Figure 19.5 Thai bhat–USD exchange rate, 1981–2007

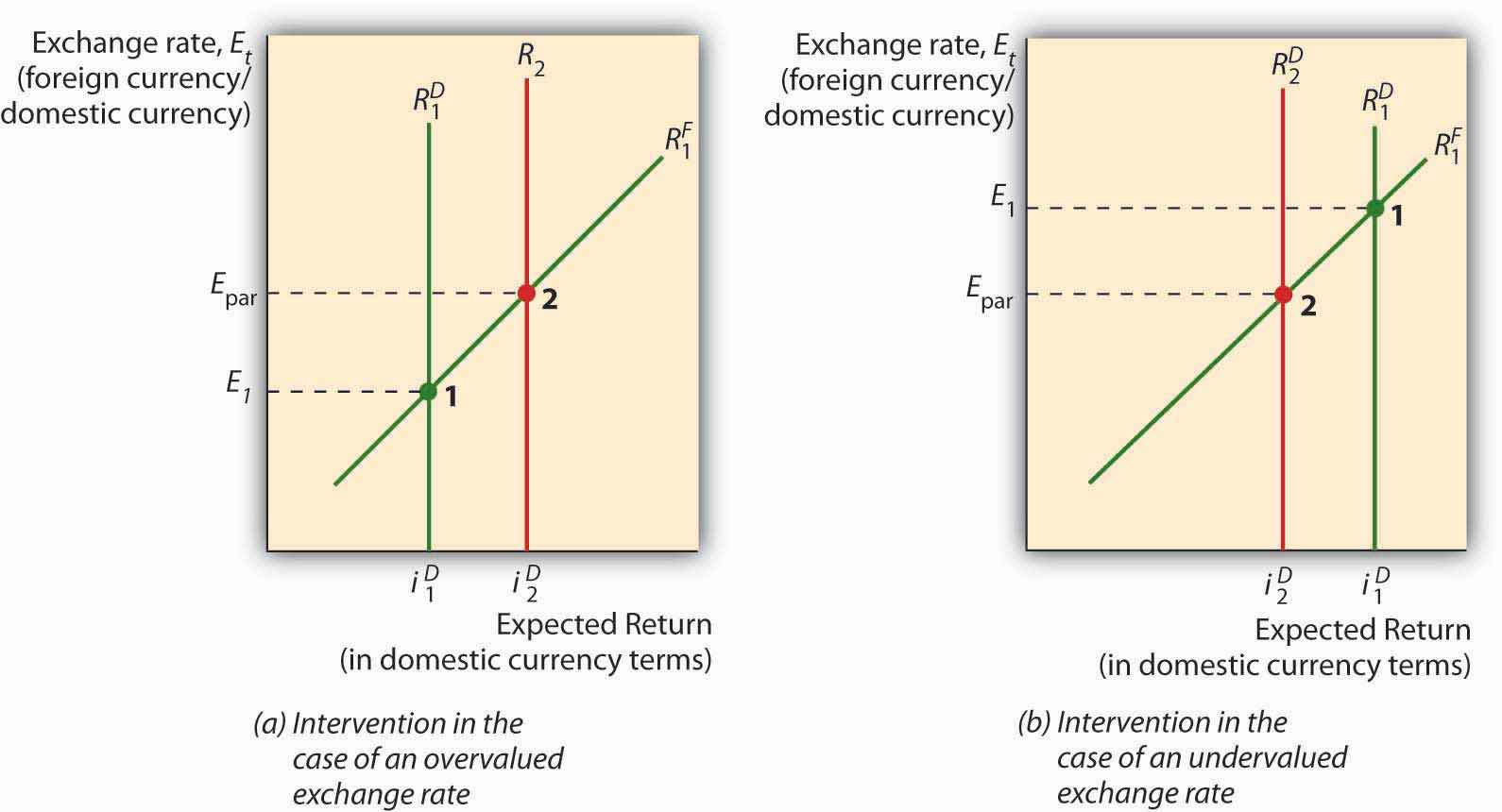

Figure 19.6 Intervening in the FX market under a fixed exchange rate regime

A graph, like the one in Figure 19.6 "Intervening in the FX market under a fixed exchange rate regime", might be useful here. When the market exchange rate (E*) is equal to the fixed, pegged, or desired central bank rate (Epeg) everything is hunky dory. When a currency is overvalued (by the central bank), which is to say that E* is less than Epeg (measuring E as foreign currency/domestic currency), the central bank must soak up domestic currency by selling international reserves (foreign assets). When a currency is undervalued (by the central bank), which is to say that when E* is higher than Epeg, the central bank must sell domestic currency, thereby gaining international reserves.

Stop and Think Box

In 1990, interest rates rose in Germany due to West Germany’s reunification with formerly communist East Germany. (Recall from Chapter 18 "Foreign Exchange" that when exchange rates are fixed, the interest parity condition collapses to iD = iF because Eef = Et.) Therefore, interest rates also rose in the other countries in the ERM, including France, leading to a slowing of economic growth there. The same problem could recur in the new European currency union or euro zone if part of the zone needs a high interest rate to stave off inflation while another needs a low interest rate to stoke employment and growth. What does this analysis mean for the likelihood of creating a single world currency?

It means that the creation of a world currency is not likely anytime soon. As the European Union has discovered, a common currency has certain advantages, like the savings from not having to convert one currency into another or worry about the current or future exchange rate (because there is none). At the same time, however, the currency union has reminded the world that there is no such thing as a free lunch, that every benefit comes with a cost. The cost in this case is that the larger the common currency area becomes, the more difficult it is for the central bank to implement policies beneficial to the entire currency union. It was for that very reason that Great Britain opted out of the euro.

Key takeaways

- Central banks influence the FX rate via unsterilized foreign exchange interventions or, more specifically, by buying or selling international reserves (foreign assets) with domestic currency.

- When central banks buy international reserves, they increase MB and hence depreciate their respective currencies by increasing inflation expectations.

- When central banks sell international reserves, they decrease MB and hence appreciate their respective currencies by decreasing inflation expectations.

19.4 The Choice of International Policy Regime

Learning Objective

- What are the costs and benefits of fixing the FX rate or keeping it within a narrow band?

Problems ensue when the central bank runs out of reserves, as it did in Thailand in 1997. The International Monetary Fund (IMF) often provides loans to countries attempting to defend the value of their currencies. It doesn’t really act as an international lender of last resort, however, because it doesn’t follow Hamilton’s née Bagehot’s Law. It simply has no mechanism for adding liquidity quickly, and the longer one waits, the bigger the eventual bill. Moreover, the IMF often forces borrowers to undergo fiscal austerity programs (high government taxes, decreased expenditures, high domestic interest rates, and so forth) that can create as much economic pain as a rapid depreciation would. Finally, it has created a major moral hazard problem, repeatedly lending to the same few countries, which quickly learned that they need not engage in responsible policies in the long run because the IMF would be sure to help out if they got into trouble. Sometimes the medicine is indeed worse than the disease!

Trouble can also arise when a central bank no longer wants to accumulate international reserves (or indeed any assets) because it wants to squelch domestic inflation, as it did in Germany in 1990–1992. Many fear that China, which currently owns over $1 trillion in international reserves (mostly USD), will find itself in this conundrum soon. The Chinese government accumulated such a huge amount of reserves by fixing its currency (which confusingly goes by two names, the yuan and the renminbi, but one symbol, CNY) at the rate of CNY8.28 per USD. Due to the growth of the Chinese economy relative to the U.S. economy, E* exceeded Epeg, inducing the Chinese, per the analysis above, to sell CNY for international reserves to keep the yuan permanently weak, or undervalued relative to the value the market would have assigned it.

You should recall from Chapter 18 "Foreign Exchange" that undervaluing the yuan helps Chinese exports by making them appear cheap to foreigners. (If you don’t believe me, walk into any Wal-Mart, Target, or other discount store.) Many people think that China’s peg is unfair, a monetary form of dirty pool. Such folks need to realize that there is no such thing as a free lunch. To maintain its peg, the Chinese government has severely restricted international capital mobility via currency controls, thereby injuring the efficiency of Chinese financial markets, limiting foreign direct investment, and encouraging mass loophole mining. It is also stuck with a trillion bucks of relatively low-yielding international reserves that will decline in value when the yuan floats (and probably appreciates strongly), as it eventually must. In other words, China is setting itself up for the exact opposite of the Southeast Asian Crisis of 1997–1998, where the value of its assets will plummet instead of the value of its liabilities skyrocketing.

In China’s defense, many developing countries find it advantageous to peg their exchange rates to the dollar, the yen, the euro, the pound sterling, or a basket of such important currencies. The peg, which can be thought of as a monetary policy target similar to an inflation or money supply target, allows the developing nation’s central bank to figure out whether to increase or decrease MB and by how much. A hard peg or narrow band effectively ties the domestic inflation rate to that of the anchor country, As noted in Chapter 18 "Foreign Exchange", however, not all goods and services are traded internationally, so the rates will not be exactly equal. instilling confidence in the developing country’s macroeconomic performance.

Indeed, in extreme cases, some countries have given up their central bank altogether and have dollarized, adopting USD or other currencies (though the process is still called dollarization) as their own. No international law prevents this, and indeed the country whose currency is adopted earns seigniorage and hence has little grounds for complaint. Countries that want to completely outsource their monetary policy but maintain seigniorage revenue (the profits from the issuance of money) adopt a currency board that issues domestic currency but backs it 100 percent with assets denominated in the anchor currency. (The board invests the reserves in interest-bearing assets, the source of the seigniorage.) Argentina benefited from just such a board during the 1990s, when it pegged its peso one-to-one with the dollar, because it finally got inflation, which often ran over 100 percent per year, under control.

Fixed exchange rates not based on commodities like gold or silver are notoriously fragile, however, because relative macroeconomic changes in interest rates, trade, and productivity can create persistent imbalances over time between the developing and the anchor currencies. Moreover, speculators can force countries to devalue (move Epeg down) or revalue (move Epeg up) when they hit the bottom or top of a band. They do so by using the derivatives markets to place big bets on the future exchange rate. Unlike most bets, these are one-sided because the speculators lose little money if the central bank successfully defends the peg, but they win a lot if it fails to. Speculator George Soros, for example, is reported to have made $1 billion speculating against the pound sterling during the ERM balance of payments crisis in September 1992. Such crises can cause tremendous economic pain, as when Argentina found it necessary to abandon its currency board and one-to-one peg with the dollar in 2001–2002 due to speculative pressures and fundamental macroeconomic misalignment between the Argentine and U.S. economies. (Basically, the United States was booming and Argentina was in a recession. The former needed higher interest rates/slower money growth and the latter needed lower interest rates/higher money growth.)

Developing countries may be best off maintaining what is called a crawling target or crawling peg. Generally, this entails the developing country’s central bank allowing its domestic currency to depreciate or appreciate over time, as general macroeconomic conditions (the variables discussed in Chapter 18 "Foreign Exchange") dictate. A similar strategy is to recognize imbalances as they occur and change the peg on an ad hoc basis accordingly, perhaps first by allowing the band to widen before permanently moving it. In those ways, developing countries can maintain some FX rate stability, keep inflation in check (though perhaps higher than in the anchor country), and hopefully avoid exchange rate crises.

Stop and Think Box

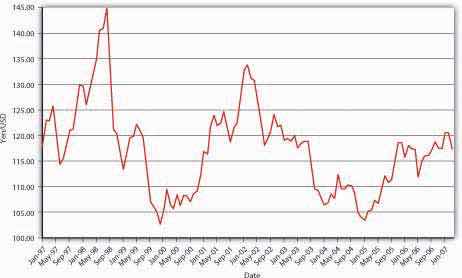

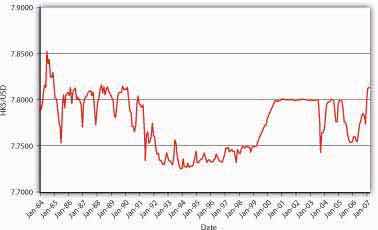

What sort of international monetary regimes are consistent with Figure 19.7 "Dollar-yen exchange rate, 1997–2007" and Figure 19.8 "Hong Kong–USD exchange rate, 1984–2007"?

Figure 19.7 Dollar-yen exchange rate, 1997–2007

Figure 19.8 Hong Kong–USD exchange rate, 1984–2007

Figure 19.7 "Dollar-yen exchange rate, 1997–2007" certainly is not a fixed exchange rate regime, or a managed float with a tight band. It could be consistent with a fully free float, but it might also represent a managed float with wide bands between about ¥100 to ¥145 per dollar.

It appears highly likely from Figure 19.8 "Hong Kong–USD exchange rate, 1984–2007" that Hong Kong’s monetary authority for most of the period from 1984 to 2007 engaged in a managed float within fairly tight bands bounded by about HK7.725 and HK7.80 to the dollar. Also, for three years early in the new millennium, it pegged the dollar at HK7.80 before returning to a looser but still tight band in 2004.

Key Takeaways

- A country with weak institutions (e.g., a dependent central bank that allows rampant inflation) can essentially free-ride on the monetary policy of a developed country by fixing or pegging its currency to the dollar, euro, yen, pound sterling, or other anchoring currency to a greater or lesser degree.

- In fact, in the limit, a country can simply adopt another country’s currency as its own in a process called dollarization.

- If it wants to continue earning seigniorage (profits from the issuance of money), it can create a currency board, the function of which is to maintain 100 percent reserves and full convertibility between the domestic currency and the anchor currency.

- At the other extreme, it can create a crawling peg with wide bands, allowing its currency to appreciate or depreciate day to day according to the interaction of supply and demand, slowly adjusting the band and peg in the long term as macroeconomic conditions dictate.

- When a currency is overvalued, which is to say, when the central bank sets Epeg higher than E* (when E is expressed as foreign currency/domestic currency), the central bank must appreciate the currency by selling international reserves for its domestic currency.

- It may run out of reserves before doing so, however, sparking a rapid depreciation that could trigger a financial crisis by rapidly increasing the real value of debts owed by domestic residents but denominated in foreign currencies.

- When a currency is undervalued, which is to say, when the central bank sets Epeg below E*, the central bank must depreciate its domestic currency by exchanging it for international reserves. It may accumulate too many such reserves, which often have low yields and which could quickly lose value if the domestic currency suddenly appreciates, perhaps with the aid of a good push by currency speculators making big one-sided bets.

19.5 Suggested Reading

Bordon, Michael, and Barry Eichengreen. A Retrospective on the Bretton Woods Systemml: Lessons for International Monetary Reform. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1993.

Eichengreen, Barry. Globalizing Capital: A History of the International Monetary System. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2008.

Gallorotti, Giulio. The Anatomy of an International Monetary Regime: The Classical Gold Standard, 1880–1914. New York: Oxford University Press, 1995.

Moosa, Imad. Exchange Rate Regimes: Fixed, Flexible or Something in Between. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2005.

Rosenberg, Michael. Exchange Rate Determination: Models and Strategies for Exchange Rate Forecasting. New York: McGraw-Hill, 2003.