This is “The Balance Sheet”, section 9.1 from the book Finance, Banking, and Money (v. 1.0).

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. You may also download a PDF copy of this book (8 MB) or just this chapter (304 KB), suitable for printing or most e-readers, or a .zip file containing this book's HTML files (for use in a web browser offline).

9.1 The Balance Sheet

Learning Objective

- What is a balance sheet and what are the major types of bank assets and liabilities?

Thus far, we’ve studied financial markets and institutions from 30,000 feet. We’re finally ready to “dive down to the deck” and learn how banks and other financial intermediaries are actually managed. We start with the balance sheet, a financial statement that takes a snapshot of what a company owns (assets) and owes (liabilities) at a given moment. The key equation here is a simple one:

ASSETS (aka uses of funds) = LIABILITIES (aka sources of funds) + EQUITY (aka net worth or capital).

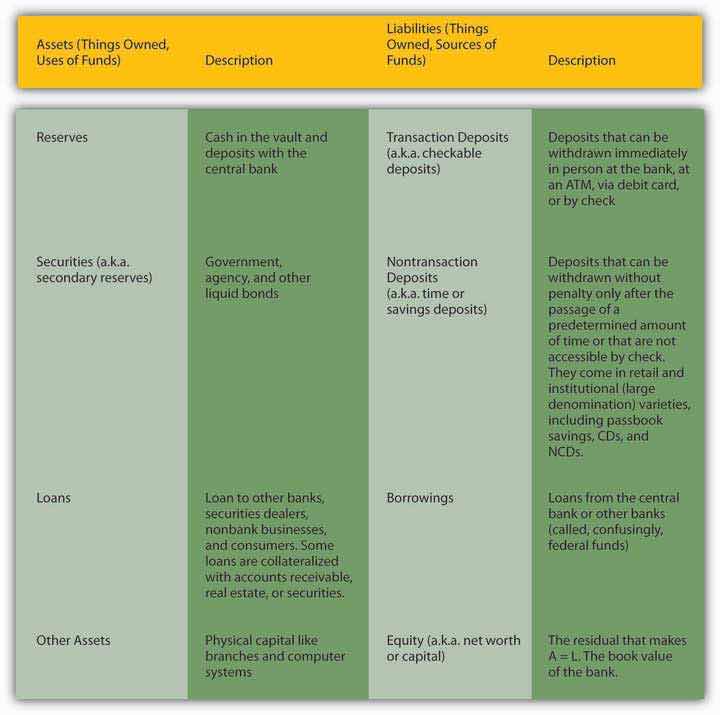

Figure 9.1 Bank assets and liabilities

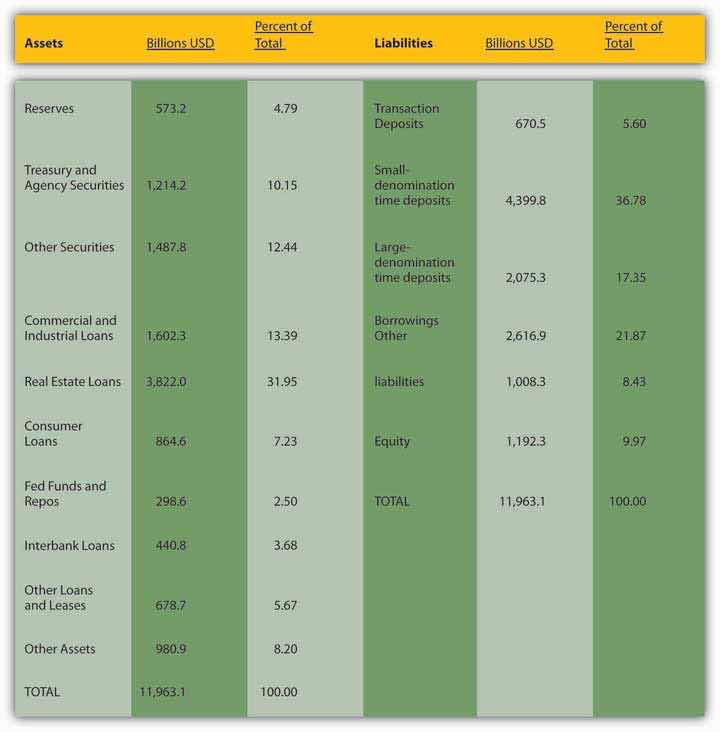

Figure 9.2 Assets and liabilities of U.S. commercial banks, March 7, 2007

Figure 9.1 "Bank assets and liabilities" lists and describes the major types of bank assets and liabilities, and Figure 9.2 "Assets and liabilities of U.S. commercial banks, March 7, 2007" shows the combined balance sheet of all U.S. commercial banks on March 7, 2007.

Stop and Think Box

In the first half of the nineteenth century, bank reservesIn this context, cash funds that bankers maintain to meet deposit outflows and other payments. in the United States consisted solely of full-bodied specie (gold or silver) coins. Banks pledged to pay specie for both their notes and deposits immediately upon demand. The government did not mandate minimum reserve ratios. What level of reserves do you think those banks kept? (Higher or lower than today’s required reservesA minimum amount of cash funds that banks are required by regulators to hold.?) Why?

With some notorious exceptions known as wildcat banks, which were basically financial scams, banks kept reserves in the range of 20 to 30 percent, much higher than today’s required reserves. They did so for several reasons. First, unlike today, there was no fast, easy, cheap way for banks to borrow from the government or other banks. They occasionally did so, but getting what was needed in time was far from assured. So basically borrowing was closed to them. Banks in major cities like Boston, New York, and Philadelphia could keep secondary reservesNoncash, liquid assets, like government bonds, that bankers can quickly sell to obtain cash., but before the advent of the telegraph, banks in the hinterland could not be certain that they could sell the volume of bonds they needed to into thin local markets. In those areas, which included most banks (by number), secondary reserves were of little use. And the potential for large net outflows was higher than it is today because early bankers sometimes collected the liabilities of rival banks, then presented them all at once in the hopes of catching the other guy with inadequate specie reserves. Also, runs by depositors were much more frequent then. There was only one thing for a prudent early banker to do: keep his or her vaults brimming with coins.

Key Takeaways

- A balance sheet is a financial statement that lists what a company owns (its assets or uses of funds) and what it owes (its liabilities or sources of funds).

- Major bank assets include reserves, secondary reserves, loans, and other assets.

- Major bank liabilities include deposits, borrowings, and shareholder equity.