This is “A Short History of Interest Rates”, section 6.1 from the book Finance, Banking, and Money (v. 1.0).

For more information on the source of this book, or why it is available for free, please see the project's home page. You can browse or download additional books there. You may also download a PDF copy of this book (8 MB) or just this chapter (475 KB), suitable for printing or most e-readers, or a .zip file containing this book's HTML files (for use in a web browser offline).

6.1 A Short History of Interest Rates

Learning Objective

- How and why has the interest rate changed in the United States over time?

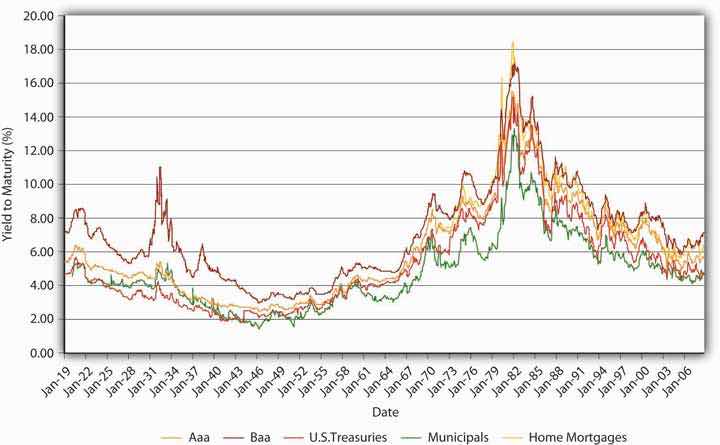

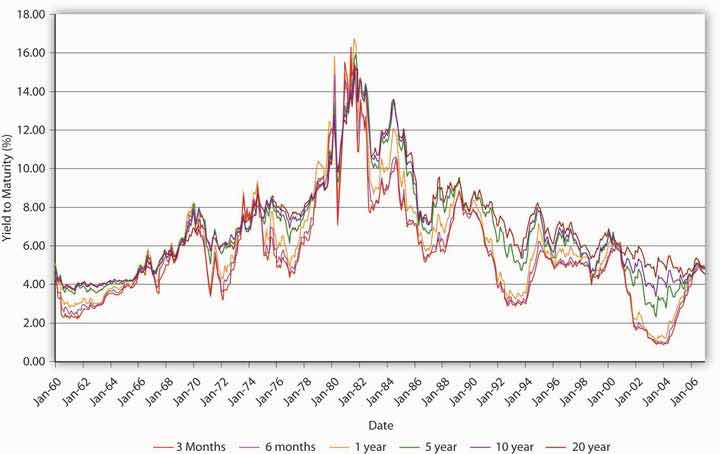

In Chapter 5 "The Economics of Interest-Rate Fluctuations" you learned about the factors that influence “the” interest rate, or in other words the general level of interest rates. For the sake of clarity, we ignored the fact that different types of financial instruments have different interest rates. We were able to do so because interest rate movements are highly correlated. In other words, they track each other closely, as Figure 6.1 "The risk structure of interest rates in the United States, 1919–2008" and Figure 6.2 "The term structure of interest rates in the United States, 1960–2006" show.

Figure 6.1 The risk structure of interest rates in the United States, 1919–2008

Figure 6.2 The term structure of interest rates in the United States, 1960–2006

The graphs reveal that interest rates generally trended downward from 1920 to 1945, then generally rose until the early 1980s, when they began trending downward again through 2005. Given what you learned in Chapter 5 "The Economics of Interest-Rate Fluctuations", you should be able to understand the basic causes underlying those general trends. During the 1920s, general business conditions were favorable (President Calvin Coolidge summed this up when he said, “The business of America is business”), so the demand for bonds increased (the demand curve shifted right), pushing prices higher and yields lower. The 1930s witnessed the Great Depression, an economic recession of unprecedented magnitude that dried up profit opportunities for businesses and hence shifted the supply curve of bonds hard left, further increasing bond prices and depressing yields. (If the federal government had not run budget deficits some years during the depression, the interest rate would have dropped even further.) During World War II, the government used monetary policy to keep interest rates low (as we’ll see in Chapter 16 "Monetary Policy Tools"). After the war, that policy came home to roost as inflation began, for the first time in American history, to become a perennial fact of life. Contemporaries called it creeping inflation. A higher price level, of course, put upward pressure on the interest rate (think Fisher Equation and Keynes’s real nominal balances). The unprecedented increase in prices during the 1970s (what some have called creepy inflation and others the Great Inflation) drove nominal interest rates higher still. Only in the early 1980s, after the Federal Reserve mended its ways (a topic to which we will return) and brought inflation under control, did the interest rate begin to fall. Positive geopolitical events in the late 1980s and early 1990s, namely, the end of the cold war and the birth of what we today call globalization, also helped to reduce interest rates by rendering the general business climate more favorable (thus pushing the demand curve for bonds to the right, bond prices upward, and yields downward). Pretty darn neat, eh?

Key Takeaways

- When general business conditions were favorable, demand for bonds increased (the demand curve shifted right), pushing prices higher and yields lower.

- When general business conditions were unfavorable, profit opportunities for businesses dried up, shifting the supply curve of bonds left, further increasing bond prices and depressing yields.

- During inflationary periods, interest rates rose per the Fisher Equation and Keynes’s real nominal balances.

- The end of the cold war and the birth of globalization helped to reduce interest rates by rendering the general business climate more favorable (thus pushing the demand curve for bonds to the right, bond prices upward, and yields downward).