Overview

The Atlantic Charter was a pivotal policy statement issued on 14 August 1941, that defined the Allied goals for the post-war world. The leaders of the United Kingdom and the United States drafted the work and all the Allies of World War II later confirmed it. The Charter stated the ideal goals of the war. The eight principal points of the Charter were:

- no territorial gains were to be sought by the United States or the United Kingdom;

- territorial adjustments must be in accord with the wishes of the peoples concerned;

- all people had a right to self-determination;

- trade barriers were to be lowered;

- there was to be global economic cooperation and advancement of social welfare;

- the participants would work for a world free of want and fear;

- the participants would work for freedom of the seas;

- there was to be disarmament of aggressor nations, and a post-war common disarmament.

Adherents of the Atlantic Charter signed the Declaration by United Nations on the 1 January 1942, which became the basis for the modern United Nations.

The Atlantic Charter made clear that America was supporting Britain in the war. Both America and Britain wanted to present their unity, regarding their mutual principles and hopes for the post-war world and the policies they agreed to follow once the Nazis had been defeated. A fundamental aim was to focus on the peace that would follow, and not specific American involvement and war strategy, although American involvement appeared increasingly likely.

The Atlantic Charter set goals for the post-war world and inspired many of the international agreements that shaped the world thereafter. The General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), the post-war independence of European colonies, and much more are derived from the Atlantic Charter.

Impact and Response

Public opinion in Britain and the Commonwealth was delighted with the principles of the meetings but disappointed that the U.S. was not entering the war. Churchill admitted that he had hoped the U.S. would finally decide to commit itself.

The acknowledgement that all peoples had a right to self-determination gave hope to independence leaders in British colonies.

The Americans were insistent that the charter was to acknowledge that the war was being fought to ensure self-determination. The British were forced to agree to these aims but in a September 1941 speech, Churchill stated that the Charter was only meant to apply to states under German occupation, and certainly not to the peoples who formed part of the British Empire.

Churchill rejected its universal applicability when it came to the self-determination of subject nations such as British India. Mohandas Gandhi in 1942 wrote to President Roosevelt: "I venture to think that the Allied declaration that the Allies are fighting to make the world safe for the freedom of the individual and for democracy sounds hollow so long as India and for that matter Africa are exploited by Great Britain..." Roosevelt repeatedly brought the need for Indian independence to Churchill's attention, but was repeatedly rebuffed. However Gandhi refused to help either the British or the American war effort against Germany and Japan in any way, and Roosevelt chose to back Churchill. India was already contributing significantly to the war effort, sending over 2.5 million men (the largest volunteer force in the world at the time) to fight for the Allies, mostly in West Asia and North Africa.

The Axis powers interpreted these diplomatic agreements as a potential alliance against them. In Tokyo, the Atlantic Charter rallied support for the militarists in the Japanese government, who pushed for a more aggressive approach against the U.S. and Britain.

The British dropped millions of flysheets over Germany to allay fears of a punitive peace that would destroy the German state. The text cited the Charter as the authoritative statement of the joint commitment of Great Britain and the U.S. "not to admit any economical discrimination of those defeated" and promised that "Germany and the other states can again achieve enduring peace and prosperity."

The most striking feature of the discussion was that an agreement had been made between a range of countries that held diverse opinions, who were accepting that internal policies were relevant to the international problem. The agreement proved to be one of the first steps towards the formation of the United Nations.

Atlantic Charter

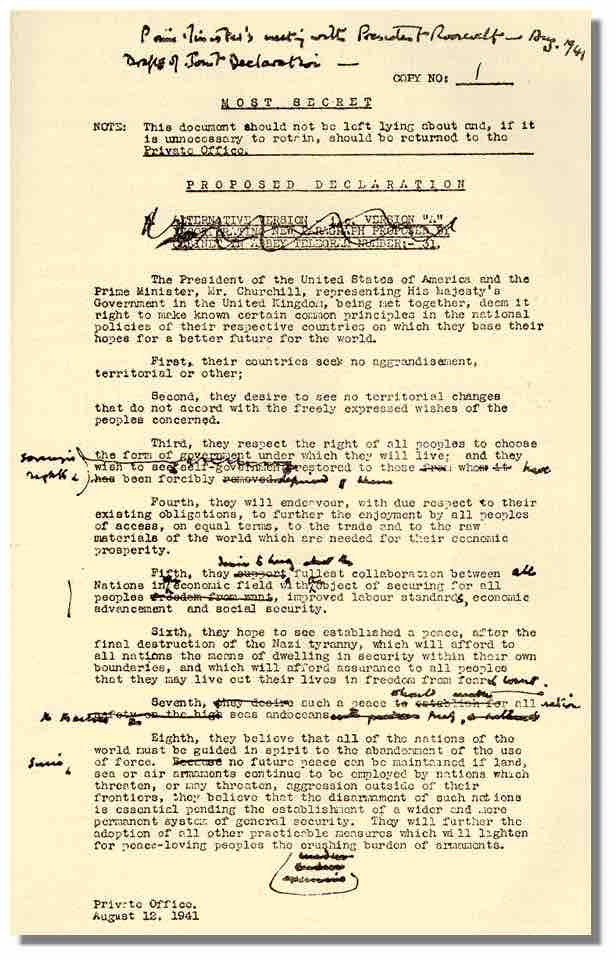

Winston Churchill's edited copy of the final draft of the Atlantic Charter.