In 1918, an influenza pandemic that became known as "Spanish Flu" or "Spanish Influenza" spread across the globe. Unusually severe and deadly, the majority of victims were healthy, young adults, in contrast to typical influenza outbreaks that predominantly affect infants, elderly, or already weakened patients. An estimated 50 million people died, 34 million more than the number of lives lost in World War I. The virus struck a fifth of the entire world’s population, making it one of the deadliest natural disasters in human history.

Bringing out the Dead

With masks over their faces, members of the American Red Cross remove a victim of the Spanish flu from a house at Etzel and Page Avenues, St. Louis, Missouri.

Masked Typist

This woman wears a mask to help protect against contagion during the Spanish influenza epidemic.

Breakout and Transmission

The Spanish Flu was a H1N1 influenza virus, which is a subtype of Influenza A with strains that can appear in humans and animals. It first appeared in the late spring of 1918 and, in its first phase, was known as the “three-day fever.” It struck without any warning signs and then dissipated, with victims recovering within days and only a few deaths being reported. Yet the flu returned with a vengeance as the year progressed. Health officials were taken off guard by the swiftness and severity of its spread and did not know how to treat or control the sickness. Some patients died within hours while others held on for a few days, succumbing after their lungs filled with fluid and resulted in suffocation.

In the United States, the disease was first observed in Haskell County, Kansas, in January 1918, prompting a local doctor to warn the U.S. Public Health Service's academic journal. On March 4, 1918, cook Albert Gitchell reported feeling sick at Fort Riley, Kansas. By noon on March 11, 1918, over 100 soldiers were hospitalized and within days, 522 men at the camp had reported sick. By March 11, 1918 the virus had spread to Queens, New York. Eventually more than 25 percent of the American population was stricken by the flu, causing such fear that within a single year U.S. life expectancy figures were lowered by 12 years.

While World War I did not cause the flu, the close quarters in which soldiers were housed increased transmission of the pandemic and amplified its mutation into an increasingly deadly form. Some speculate the immune systems of soldiers were weakened by malnourishment, while the stress of combat and chemical attacks increased their susceptibility.

Another large factor in the worldwide occurrence of the spread of the flu was increased travel. Modern transportation systems made it easier for soldiers, sailors, and civilian travelers to spread the disease, especially with the increase of troop movements during the war.

In August 1918, a more virulent strain appeared simultaneously in Brest, France, Freetown, Sierra Leone in West Africa, and Boston, Massachusetts in the United States. Allied troops came to call it the "Spanish Flu," primarily because the pandemic received greater press attention after it moved from France to Spain in November 1918. Spain was not involved in the war and had not imposed wartime censorship.

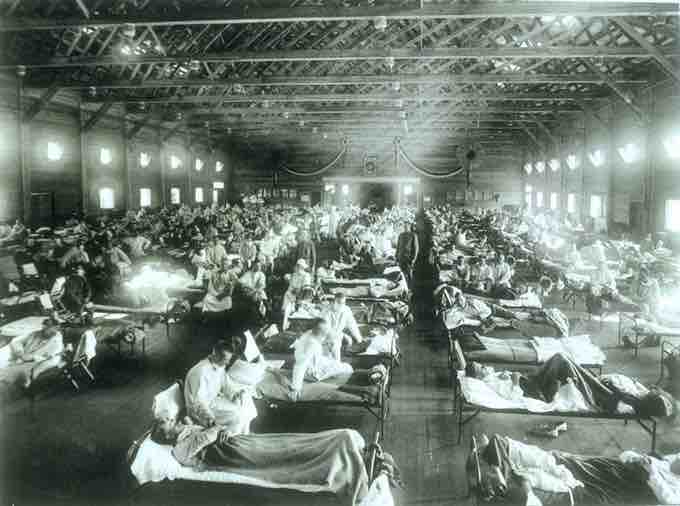

Spanish Influenza Ward

Soldiers from Fort Riley, Kansas are ill with Spanish influenza at a hospital ward at Camp Funston in 1918, where the worldwide pandemic is hypothesized by some to have begun.

Deadly Second Wave

The second wave of the pandemic struck in the autumn of 1918 and was much deadlier than the first. The first wave resembled typical flu epidemics in which those most at risk are the sick and elderly, while younger, healthier people recovered easily. But in August 1918, when the second wave began in France, Sierra Leone and the United States, the virus had mutated into a much deadlier form.

This mutation has been attributed to the circumstances of the First World War. In civilian life, evolutionary pressures favor a mild strain of flue: those who get very sick stay home, and those mildly ill continue with their lives, thereby spreading the mild strain. In the trenches, however, the evolutionary pressures were reversed: soldiers with a mild strain remained where they were, while the severely ill were sent on packed trains to overcrowded field hospitals, spreading the deadlier virus.

The second wave began and the flu quickly spread around the world again. It was the same flu as the first wave, but it was now far more deadly. Most of those who recovered from first-wave infections were immune, but mutation caused the infection to attack those who, like the soldiers in the trenches, were otherwise young, healthy adults. Consequently, during modern pandemics, health officials pay attention when a virus reaches places with social upheaval, looking for deadlier strains of the virus to develop. This effect was most dramatically illustrated in Copenhagen, which escaped with a combined mortality rate of just 0.29 percent (0.02 percent in first wave and 0.27 percent in second wave) because of exposure to the less-lethal first wave.

End of the Pandemic

After the deadly second wave, new cases dropped abruptly to almost nothing after its original peak. In Philadelphia, 4,597 people died in the week ending October 16, but by November 11, influenza had almost disappeared from the city. One explanation for the rapid decline of the disease is that doctors simply became more knowledgeable and skilled at preventing and treating the pneumonia that developed after the victims contracted the virus.