The industrial cities of the North and Midwest experienced severe labor shortages following World War I. Northern manufacturers recruited throughout the South, sparking an exodus of African-American workers that became known as the Great Migration. This resulted in postwar social tensions related to the demobilization of veterans of World War I, both black and white, and competition for jobs among ethnic whites and blacks. At the height of the tensions came the Red Summer of 1919, when whites carried out open acts of violence against blacks, who were forced to fight back. Beyond the problems that occurred due to ethnic tensions within America, there was also racial friction resulting in the great influx of European immigrants. This backlash by those born American against people who sought a new life in the United States was known as nativism.

Nativism in America

The movement gained its name from the term "Native American", not meaning indigenous or American Indian, but rather those descended from the inhabitants of the original Thirteen Colonies. Nativist movements included the Know Nothing or American Party of the 1850s, the Immigration Restriction League of the 1890s, the anti-Asian movements in the West, resulting in the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 and the "Gentlemen's Agreement of 1907," by which Japan's government stopped emigration to America. Labor unions were strong supporters of limits on immigration because of fears they would lower wages and make it harder to organize unions.

In the 1890-1920 era, nativists and labor unions campaigned for immigration restriction. A favorite plan was the literacy test to exclude workers who could not read or write English. Responding to these demands, opponents of the literacy test called for the establishment of an immigration commission to focus on immigration as a whole. The United States Immigration Commission, also known as the Dillingham Commission, was created and tasked with studying immigration and its effect on the United States. The findings of the commission further influenced immigration policy and upheld the concerns of the nativist movement.

Following World War I, nativists in the 1920s focused their attention on Catholics, Jews, and southeastern Europeans, and realigned their beliefs behind racial and religious nativism. The racial concern of the anti-immigration movement was linked closely to the eugenics movement that was sweeping the United States. Led by Madison Grant's book, The Passing of the Great Race, nativists grew more concerned with the racial purity of the United States. In his book, Grant argued that the American racial stock was being diluted by the influx of new immigrants from the Mediterranean, the Balkans, and the Polish ghettos. The Passing of the Great Race achieved wide popularity among Americans and influenced immigration policy. A wide national consensus sharply restricted the overall inflow of immigrants, especially those from southern and eastern Europe. The second Ku Klux Klan, which flourished in the U.S. in the 1920s, used strong nativist rhetoric, but the Catholics led a counterattack.

After intense lobbying from the nativist movement, the United States Congress passed the Emergency Quota Act in 1921. This bill was the first to place numerical quotas on immigration. It capped the inflow to 357,803 immigrants arriving from outside of the western hemisphere. However, this bill was only temporary, as Congress began debating a more permanent bill.

The Emergency Quota Act was followed with the Immigration Act of 1924, a more permanent resolution. This law reduced the number of immigrants able to arrive from 357,803 to 164,687. Though this bill did not fully restrict immigration, it considerably curbed the flow of immigration into the United States. During the late 1920s, an average of 270,000 immigrants were allowed to arrive, mainly because of the exemption of Canada and Latin American countries.

The Great Migration and Work Competition

Beginning about 1915 through the 1930s, in what became known as the Great Migration, more than 1.5 million blacks left the South and moved to Northern cities seeking better living conditions including more work and an escape from the common vigilante practice of lynching, which were extra-judicial killings of blacks for various reasons.

Segregation was still a reality, even in the North, with competition for jobs and housing as blacks entered cities, which also drew millions of immigrants from Eastern and Southern Europe. As more African-Americans moved northward, they encountered racism in which they had to battle over territory, often against ethnic Irish, who were defending their power bases. While they faced difficulties, the chances for African-Americans were still far better in the North.

African-Americans had to make great cultural changes, as most went from rural areas to major industrial cities and had to adjust from being rural laborers to urban workers. Black workers filled new positions in expanding industries, such as the railroads, as well as many jobs formerly held by whites. In some cities, they were hired as strike breakers, especially during the strikes of 1917. This increased resentment among many working class whites, immigrants, or first-generation Americans. Following the war, rapid demobilization of the military without a plan for absorbing veterans into the job market, and the removal of price controls, led to unemployment and inflation, which further increased competition for jobs.

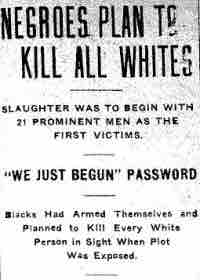

Newspaper headlines

This inflammatory newspaper headline appeared during the Elaine Race Riot of 1919. Racial tensions between whites and blacks increased during 1919.

The Red Summer of 1919

The Red Summer is a term for the race riots that occurred in more than three dozen cities in the United States during the summer and early autumn of 1919. In most instances, whites fell upon African-Americans in mass attacks that developed out of strikes and economic competition.

The Chicago Race Riot was the worst example of the mob violence that swept the country. On July 27, 1919, an African-American teenager drowned in Lake Michigan after being stoned by a group of whites for violating the unwritten segregation between whites and blacks on the city’s beaches. Police refusal to arrest the white man identified by witnesses as the instigator sparked rioting and open violence between black and white gangs, with most of the unrest occurring on the South Side near the city stockyards. When the rioting and fighting finally ended on the 3rd of August, 15 whites and 23 blacks were dead, another 500 were injured, and 1,000 black families lost their homes to fires set by rioters.

Chicago Race Riot

A white gang looking for African Americans during the Chicago Race Riot of 1919. A lack of plans for demobilization after World War I exacerbated racial and economic tensions in many cities across the U.S.

The Haynes Report

In the autumn of 1919, Dr. George Edmund Haynes, the director of Negro Economics for the U.S. Department of Labor, drafted a study of the violence-filled summer to be used by the U.S. Senate Committee on the Judiciary. The so-called Haynes Report identified 38 separate riots in widely scattered cities, in which whites attacked blacks. In addition, Haynes reported that between January and September 1919, white mobs lynched at least 43 African-Americans, with 16 hanged and others shot, while another eight men were burned at the stake.

Published in major newspapers, the Haynes Report was a call for national action. Haynes said the states had shown themselves "unable or unwilling" to put a stop to lynchings, and seldom prosecuted the murderers. The fact that white men had been lynched in the North as well, he argued, demonstrated the national nature of the overall problem: "It is idle to suppose that murder can be confined to one section of the country or to one race."

African-American Advocacy

Unlike earlier race riots in U.S. history, the 1919 events were among the first in which blacks widely resisted white attacks. In September 1919, in response to the Red Summer, the African Blood Brotherhood, a radical black liberation organization, formed in northern cities to serve as an "armed resistance" movement. Protests and appeals to the federal government continued for weeks. A letter in late November from the National Equal Rights League appealed to President Woodrow Wilson's international advocacy for human rights: "We appeal to you to have your country undertake for its racial minority that which you forced Poland and Austria to undertake for their racial minorities."

Government Activity

During the Chicago riot, U.S. Department of Justice officials reported to the press that supposed communist groups like the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) and Bolshevik supporters were "spreading propaganda to breed race hatred. FBI agents filed reports that leftist views were winning converts in the black community. One cited the work of the NAACP "urging the colored people to insist upon equality with white people and to resort to force, if necessary."

J. Edgar Hoover, at the start of his career in government, analyzed the riots for Attorney General A. Mitchell Palmer, blaming the events on "Negro agitation" and incitement by socialists. In November, Palmer reported to Congress on the threat that anarchists and Bolsheviks posed to the government. More than half the report documented radicalism in the black community and the "open defiance" black leaders advocated in response to racial violence and the summer's rioting.