The home front of the United States in World War I saw a systematic mobilization of its entire population and economy to produce the soldiers, food, munitions, and money needed to win the war. Although the U.S. entered the war in 1917, there had been very little planning or recognition of the problems other Allies had to solve on their home fronts. As a result, the level of confusion was high in the first 12 months until efficiency took control.

Instituting a Military Draft

The government under President Woodrow Wilson decided to rely primarily on conscription rather than voluntary enlistment to raise military manpower. The Selective Service Act of 1917 established a "liability for military service of all male citizens" and authorized a selective draft of men between 21 and 31 years of age. The law was carefully drawn to place each man in his proper niche in the national war effort, which included exemptions from military service for those who fell into categories such as having dependents, working in essential occupations, and religion. The act prohibited all forms of bounties, substitutions, or purchase of exemptions, all of which had been prevalent during the Civil War.

Oversight and administration of the draft was entrusted to local boards of civilians that issued draft calls, which were ordered by numbers drawn in a national lottery, and determined exemptions. In 1917 and 1918, approximately 24 million men were registered and nearly 3 million inducted into the armed forces.

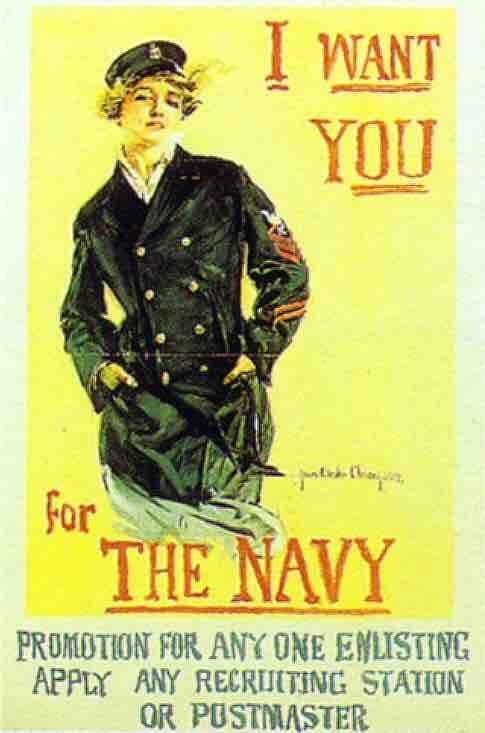

Recruiting Soldiers

As part of massive mobilization efforts, young American men volunteered or were conscripted into the armed forces.

Establishing Temporary Agencies

The war came in the midst of the Progressive Era, when efficiency and expertise were highly valued. The federal government established a multitude of temporary agencies to bring together the expertise necessary to redirect the economy into the production of munitions and food for the war, as well as new ideas to motivate the working populace.

Congress authorized President Wilson to create between 500,000 and 1 million new jobs in 5,000 new federal agencies. The War Labor Administration (WLA), headed by Wilson’s Secretary of Labor, Scottish-born former Congressman William B. Wilson, oversaw most of the wartime labor programs and included a War Labor Board to adjudicate disputes. The WLA also established the Women in Industry Service that eventually grew into a permanent Women’s Bureau in the Department of Labor, a Training and Dilution Service to help simplify skilled jobs, a Division of Negro Economics, Farm Service Division, Working Conditions Service, and Housing and Transportation Bureau that helped accommodate the living conditions of war workers.

The Department of Labor’s new Employment Service attracted workers from the South and Midwest to war industries in the East and was used by federal production offices to hire fresh employees. The service also brought 110,000 workers into the country from Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands, enrolled 1 million people in a reserve labor force, and in early 1918 began mobilizing 3 million workers for agriculture, ship building, and defense plant positions.

While Wilson’s policies created numerous jobs in these new agencies, he also had the less distinguished achievement of segregating the federal workforce. Upon taking office in 1913, Wilson placed many pro-segregation Southerners in positions throughout the government and ordered the reversal of post-Civil War Reconstruction policies that had integrated federal agencies and enabled African-Americans to work alongside white employees. This change reached throughout the civil service, including the expansive Postal Service, where African-American employees were downgraded and transferred out of jobs that interacted with the public. Segregationist policies continued into World War I. The War Department drafted hundreds of thousands of African-American men into the army with equal pay, but placed them in segregated units with black soldiers led by white officers. Largely kept out of combat, a group of black service members protested directly to Wilson but were met by his response, “Segregation is not a humiliation but a benefit, and ought to be so regarded by you gentlemen.”

Economic Confusion

The first 15 months of the war effort on the home front involved an amazing parade of mistakes, misguided enthusiasm and confusion. Most Americans were willing to pitch in but were not clear on their proper roles, while Washington was often unable to make clear decisions about actions, timing, or even who was in charge. The coal shortage that struck the nation in December 1917 exemplified the confusion.

Coal was the major source of energy and heat. Plenty of coal was mined, but a crisis developed when 44,000 loaded freight and coal cars were tied up in horrendous traffic jams in the rail yards of the East Coast, leaving 200 ships waiting in New York harbor for the delayed cargo. It was not until March 1918 that Washington took control, using measures such as nationalizing coal mines and railroads for the duration of the war, shutting factories one day each week to save fuel, and enforcing a strict priority system.

Labor Unions in World War I

Nearly all labor unions strongly supported the war effort and during the conflict the number of strikes were minimal, wages soared and full employment was reached. President Wilson appointed Samuel Gompers, head of the American Federation of Labor (AFL), to the powerful Council of National Defense. AFL membership soared to 2.4 million in 1917, and its unions strongly encouraged their young men to enlist in the military. They fiercely opposed efforts to reduce recruiting and slow war production by groups like the International Workers of the World (IWW), which was controlled by anti-war socialists and subsequently shut down by the federal government.

To keep factories running smoothly, the president established the National War Labor Board in 1918, which forced management to negotiate with existing unions. In 1919, the AFL tried to make its gains permanent and called a series of major strikes in meat, steel and other industries. The strikes ultimately failed, however, forcing unions back to positions similar to those around 1910.

Mobilizing Farming and Food

During World War I, food production fell dramatically, especially in Europe where agricultural labor had been recruited into military service and many farms were devastated by the conflict. Numerous efforts were made in the United States to bolster domestic morale in conjunction with keeping the agriculture sector afloat. The U.S. Food Administration under Herbert Hoover managed the nation's food distribution and prices, and launched a massive campaign to teach Americans to economize their food budgets. Apart from "Wheatless Wednesdays" and "Meatless Tuesdays" due to poor harvests in 1916 and 1917, there were "Fuelless Mondays" and "Gasless Sundays" to preserve coal and gasoline.

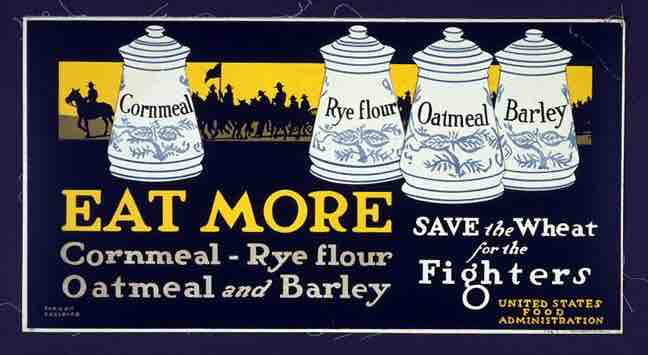

"Eat More"

The United States Food Administration urges Americans to eat non-traditional grains, saving wheat for fighting soldiers.

StartFragment

In March 1917, Charles Lathrop Pack organized the National War Garden Commission and launched the war garden campaign. Pack believed the supply of food could be greatly increased without the use of land and manpower already engaged in agriculture, and without the significant use of transportation facilities needed for the war. The campaign promoted the cultivation of available private and public lands, resulting in the production of foodstuff exceeding $1.2 billion by the end of the war. From 1914 to 1919, gross farm income increased more than 230 percent.

A poster campaign encouraged the planting of "victory gardens", emphasizing to home front urbanites and suburbanites that the produce from their gardens would help lower the price of vegetables needed by the U.S. War Department to feed the troops, thus saving money that could be spent elsewhere on the military. First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt directed the planting of a victory garden on the White House grounds to support the initiative.

Women War Gardeners, 1918

War gardeners in the Washington, D.C. vicinity, circa 1918. Home front efforts led by women, such as large war gardens and domestic "victory gardens," were an important part of U.S. entry into WWI.

Although government officials initially feared this movement would hurt the food industry, basic information about gardening appeared in public services booklets distributed by the Department of Agriculture and agribusiness corporations such as International Harvester and Beech-Nut. The Agriculture Department estimated that more than 20 million victory gardens were planted, with between nine and 10 million tons of fruit and vegetables harvested in these home and community plots, equaling all commercial production of fresh vegetables.

The Women's Land Army of America (WLAA) was created to replace male agricultural workers who were called up to the military. Modeled on the British Women’s Land Army, WLAA members were sometimes known as "farmerettes.” The WLAA operated from 1917 to 1921, employing between 15,000 and 20,000 urban women. Many were college educated, and units were associated with colleges. The WLAA was supported by Progressives like Theodore Roosevelt and was strongest in the West and Northeast, where it was associated with the suffrage movement. Opposition came from Nativists, President Wilson’s agitators, and others who questioned the women's strength and the effect of the work on their health. Yet the latter arguments were largely disproved, not only by the successful efforts of the WLAA, but by the widespread increase in women who joined the workforce to support the economy and the war effort.

Women Workers in World War I

As one of the first total wars, World War I mobilized women in unprecedented numbers on all sides. Some joined the military to take the jobs of men who had transferred to fighting units, serving as pilots to transport supplies, test planes and tow targets for artillery practice. The vast majority were drafted into the civilian workforce to replace conscripted men, taking traditionally male jobs working on factory assembly lines producing tanks, trucks and munitions. For the first time, department stores employed African-American women as elevator operators and cafeteria waitresses. This proved women were capable of a variety of work, which added to the voting rights controversy that came later.

As well as paid jobs, women were also expected to take on voluntary work such as packing coal into sacks for distribution wherever it was needed, or rolling bandages, knitting clothes and preparing hampers for soldiers on the front. Millions joined the Red Cross as volunteers to help soldiers and their families. Most important, the morale of women remained high and, with rare exceptions, women did not protest the draft.