U.S. War Propaganda During World War I

The Creel Committee

Hoping to influence public opinion favorably toward American participation in World War I, President Woodrow Wilson established the Committee on Public Information (CPI) through Executive Order 2594 on April 13, 1917. Tasked with creating a prolonged propaganda campaign, the group that became known as The Creel Committee consisted of politician and journalist George Creel, the committee chairman; Robert Lansing, Secretary of State; Newton D. Baker, Secretary of War; and Secretary of the Navy Josephus Daniels.

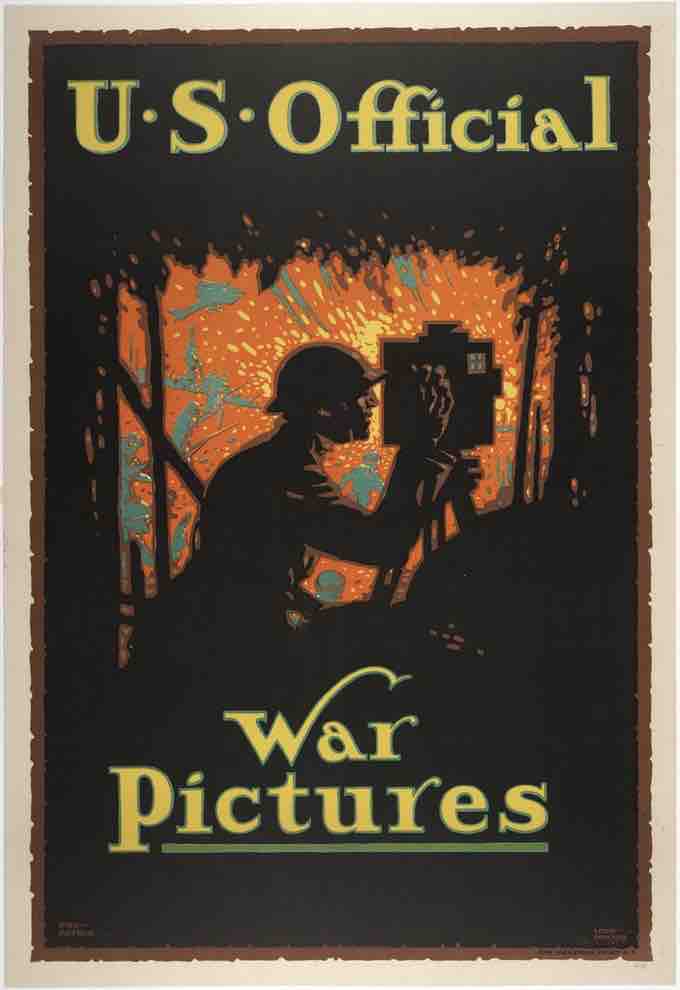

The CPI at first used factual information, but manipulated – or “spun” – the material to present an upbeat picture of the American war effort. The avenues of distribution for the message included all types of current media and communications: newsprint, posters, radio, telegraphs, and movies.

World War I Propaganda

The Creel Committee used all forms of media, such as this poster, to spread the US message during World War I.

The committee also used direct human media in the form of about 75,000 "Four Minute Men," volunteers who delivered positive public messages about the war. Using their own words and avoiding "hymns of hate" that seemed negative, the topics included the draft, rationing, war bond drives, victory gardens, and why America had joined the fight. These talks were kept to four minutes, often during the time when reels were changed in movie theaters, which was considered the ideal length of time the average human attention span could be effectively maintained. By the end of the war, the Four Minute Men had made more than 7.5 million speeches to 314 million people in 5,200 American communities.

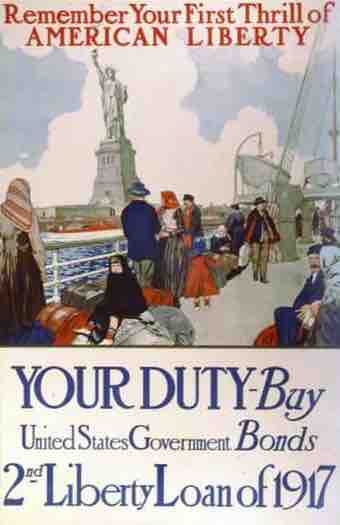

"Remember Your First Thrill of AMERICAN LIBERTY"

World War I propaganda poster urging Americans to buy Liberty Bonds (1917).

The CPI staged other personal events designed for specific ethnic and class groups. In one example, Irish-American tenor John McCormack sang at Mount Vernon before an audience representing Irish-American organizations. Endorsed by labor union leader Samuel Gompers, the committee also targeted American workers, filling factories and offices with posters designed to promote the critical role of American labor in a successful war effort.

The CPI was so thorough that some historians used a typical Midwestern farm family to explain the reach and impact of the committee’s activities:

"Every item of war news they saw—in the country weekly, in magazines, or in the city daily picked up occasionally in the general store—was not merely officially approved information but precisely the same kind that millions of their fellow citizens were getting at the same moment. Every war story had been censored somewhere along the line— at the source, in transit, or in the newspaper offices in accordance with ‘voluntary' rules established by the CPI. "

Hollywood and Propaganda

The nascent American film industry produced a variety of propaganda films. The most successful was 1918’s The Kaiser, the Beast of Berlin, a "sensational creation" designed to rouse the audience against the German ruler. There were also comedies including the animated Mutt and Jeff series, with hits such as At The Front. The greatest artistic success, also in 1918 and considered a landmark in film, was Charlie Chaplin's Shoulder Arms, which followed the star from his induction into the military, his accidental penetration of German lines, and his eventual return after capturing the Kaiser and German Crown Prince and winning over a pretty French girl.

Impact of WWI Propaganda

Over just 28 months, from April 1917 to August 1919, the CPI’s campaign produced intense anti-German hysteria among Americans, as well as leaving big business deeply impressed with large-scale propaganda’s obvious potential for controlling public opinions and tastes.

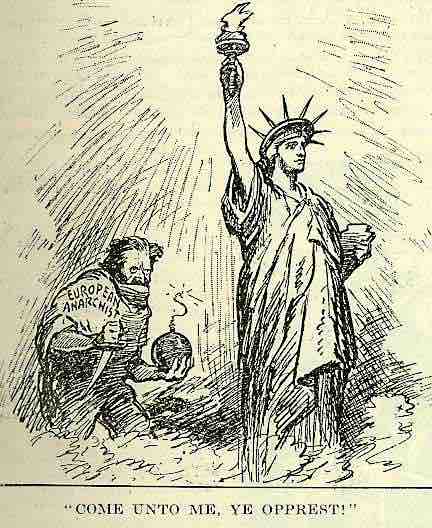

"Come unto me, ye opprest! "

First Red Scare depiction of a "European Anarchist" attempting to destroy the Statue of Liberty.

Following the war, however, propaganda and its obvious misleading nature gained a growing negative connotation. The Creel Committee became so unpopular that Congress ceased its activities without even providing funding to organize and archive its papers. The effectiveness of the committee’s techniques was not forgotten, though, as the onset of the world’s next great conflict in 1939 saw revived use of propaganda and information “spin” as a weapon of war, notoriously by Hitler's top polemicist, German Minister of Propaganda Joseph Goebbels, but also by the British Ministry of Information and again by the United States through the efforts of the Office of War Information.