Overview: The Civil Rights Movement

The Civil Rights Movement (1955–1968) refers to the social movements led by African Americans in the United States aimed at exposing rampant (and often legalized) racial discrimination and achieving equal rights and liberation for African Americans. The emergence of the Black Power Movement, which lasted roughly from 1966 to 1975, enlarged the aims of the Civil Rights Movement to include racial dignity, economic and political self-sufficiency, and freedom from oppression by white Americans.

Most of the credit for progress toward racial equality in the Unites States lies with grassroots activists. Indeed, it was campaigns and demonstrations by ordinary people that spurred the federal government to eventually take legislative action. While Congress played a role by passing the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the Voting Rights Act of 1965, and the Civil Rights Act of 1968, the actions of civil rights groups such as CORE, the SCLC, and SNCC were instrumental in forging new paths, pioneering new techniques and strategies, and achieving breakthrough successes.

Increasing Political Resistance

The key civil rights events of the 1950s (Brown v. Board of Education in 1954; Rosa Parks and the Montgomery Bus Boycott from 1955-1956; and the desegregation of Little Rock in 1957) expanded into other forms of protest in the 1960s. For many people inspired by the victories of Brown v. Board of Education and the Montgomery Bus Boycott, the glacial pace of progress throughout the country was frustrating if not intolerable. In some places, such as Greensboro, North Carolina, local NAACP chapters had been influenced by whites who provided financing for the organization. This aid, together with the belief that more forceful efforts at reform would only increase white resistance, had persuaded some African American organizations to pursue a “politics of moderation” instead of attempting to radically alter the status quo. Martin Luther King Jr.’s inspirational appeal for peaceful change in the city of Greensboro in 1958, however, planted the seed for a more assertive civil rights movement.

Martin Luther King, Jr

Martin Luther King, Jr. was an American clergyman and activist who championed racial equality through nonviolence yet fierce resistance.

The movement was characterized by major campaigns of civil resistance. During the 1960s, acts of nonviolent protest and civil disobedience produced crisis situations between activists and government authorities. Federal, state, and local governments, not to mention local businesses and communities, often responded immediately and violently to these situations in ways that highlighted the inequities faced by African Americans.

SNCC and Participatory Democracy

The 1960s brought sit-ins to Greensboro and Nashville, while Freedom Riders challenged segregation in interstate travel all over the South. Grassroots civil rights activist Ella Baker pushed for a “participatory Democracy” that built on the grassroots campaigns of active citizens instead of deferring to the leadership of educated elites and experts. As a result of her actions, in April 1960, the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) formed to carry the battle forward. Within a year, more than one hundred cities had desegregated at least some public accommodations in response to student-led demonstrations. The sit-ins inspired other forms of nonviolent protest intended to desegregate public spaces. “Sleep-ins” occupied motel lobbies, “read-ins” filled public libraries, and churches became the sites of “pray-ins.” SNCC spearheaded voter registration campaigns all over the South, particularly Mississippi in 1964.

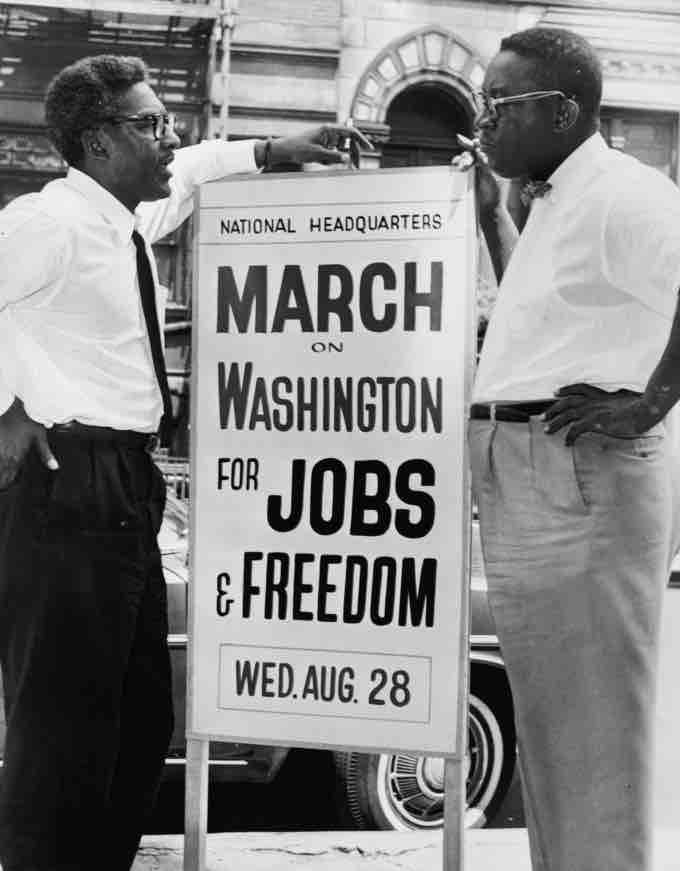

March on Washington

The organizers of the march on August 7, 1963.

Exposing State Violence

Other gatherings of civil rights activists ended tragically, and some demonstrations were intended to reveal the all-too-often hostile response from whites and the inhumanity of the Jim Crow laws and their supporters. In 1963, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) led by King mounted protests in some 186 cities throughout the South. The campaign in Birmingham that began in April and extended into the fall of 1963 attracted the most notice, however, when a peaceful protest was met with violence by police, who attacked demonstrators, including children, with fire hoses and dogs. The world looked on in horror as innocent people were assaulted and thousands arrested. King himself was jailed on Easter Sunday, 1963, and, in response to the pleas of white clergymen for peace and patience, he penned one of the most significant documents of the struggle—“Letter from a Birmingham Jail.” In the letter, King argued that African Americans had waited patiently for more than three hundred years to be given the rights that all human beings deserved; the time for waiting was over.

The March on Washington

Perhaps the most famous of the civil rights-era demonstrations was the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, held in August 1963, on the 100th anniversary of Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation. Its purpose was to pressure President Kennedy to act on his promises regarding civil rights. The date was also the 8th anniversary of the brutal racist murder of fourteen-year-old Emmett Till in Money, Mississippi. As the enormous crowd gathered outside the Lincoln Memorial and spilled across the National Mall, Martin Luther King, Jr. delivered his most famous speech. In “I Have a Dream,” King called for an end to racial injustice in the United States and envisioned a harmonious, integrated society. The speech marked a high point of the civil rights movement and established the legitimacy of its goals. However, it did not prevent white terrorism or dismantle white supremacy, nor did it permanently sustain the tactics of nonviolent civil disobedience.

New Legislation

The passage of Civil Rights Act of 1964 banned discrimination based on "race, color, religion, or national origin" in employment practices and public accommodations. The Voting Rights Act of 1965 restored and protected voting rights for African Americans that had been imposed upon since the Civil War, and the Immigration and Nationality Services Act of 1965 dramatically opened up entry into the U.S. for immigrants outside of traditional European groups. The Fair Housing Act of 1968 banned discrimination in the sale or rental of housing. African Americans re-entered politics in the South, and across the country young people were inspired to action.

Fair Housing Protest

Seattle, Washington, 1964; two African Americans and one white ally hold signs and confront police and racial discrimination in housing sales.

King's Assassination

The vision of whites and African Americans working together peacefully to end racial injustice suffered a severe blow with the death of Martin Luther King, Jr. in Memphis, Tennessee, in April 1968. King had gone there to support sanitation workers trying to unionize. In the city, he found a divided civil rights movement: older activists who supported his policy of nonviolence and younger African Americans who advocated a more militant approach. On April 4, King was shot and killed by James Earl Ray, a white man from Illinois, while standing on the balcony of his motel. Within hours, the nation’s cities exploded with violence as groups of angry activists, shocked by his murder, retaliated by burning local inner-city businesses that were not owned by blacks and often targeted African American customers with hostility and discrimination. After Martin Luther King, Jr.'s assassination, nonviolence gave way to more militant approaches by SNCC and the Black Power Movement (with its subgroup, the Black Panther Party).

Far-Reaching Effects

The growing African-American civil rights movement also spawned civil rights movements for other marginalized groups during the 1960s. Each of these movements could hardly be considered self-contained; rather, they emerged from and encouraged one another. These other movements included a new wave of feminism and a sexual revolution, as well as calls for Native American, Latino, and gay and lesbian rights.