Overview

In the 1960 election, the incumbent president, Republican Dwight D. Eisenhower, had already served two terms and thus was not eligible to run again. The Republican Party nominated Richard Nixon, Eisenhower's Vice-President, while the Democrats nominated John F. Kennedy, a Senator from Massachusetts. Kennedy was elected in the closest election based on the electoral college vote since 1916.

The Nominees

Democratic Nomination

Senator John F. Kennedy initially faced opposition from some Democratic Party elders who claimed Kennedy was too youthful and inexperienced to be president. However, JFK, as he came to be known, had an effective campaigning strategy even in the primaries.

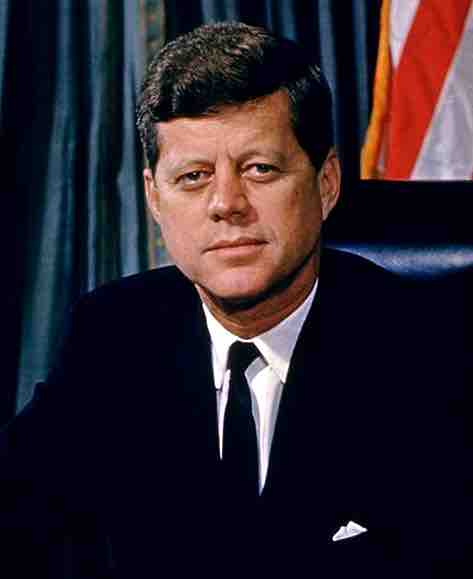

John F. Kennedy

Former President John F. Kennedy signed the Equal Pay Act into law in 1963.

In the week before the Democratic National Convention, two new candidates challenged Kennedy: Lyndon B. Johnson, the powerful Senate Majority Leader from Texas, and Adlai Stevenson, the party's nominee in 1952 and 1956. However, neither Johnson nor Stevenson were a match for the talented and highly efficient Kennedy campaign team, and Kennedy won the Democratic Party nomination. Kennedy asked Johnson to be his running mate.

Republican Nomination

Eisenhower's Vice President, Richard Nixon, was the obvious choice for the Republican nomination. Early on in the campaign season, in 1959, it looked as though Nixon might face a serious challenge for the GOP nomination from New York Governor Nelson Rockefeller. However, Rockefeller declined to run, and Nixon did not face any significant opposition for the Republican nomination.

Richard Nixon

Nixon was the Republican Party candidate in the 1960 election.

At the Republican National Convention, Nixon was the overwhelming choice of the delegates. Nixon chose United Nations Ambassador Henry Cabot Lodge, Jr. to be his running mate. Lodge's foreign-policy credentials fit into Nixon's strategy of campaigning more on foreign policy than domestic policy.

The Campaign

Nixon's "Bad Luck"

Both Kennedy and Nixon drew large and enthusiastic crowds throughout the campaign. In August of 1960, most polls gave Nixon a lead over Kennedy. However, Nixon was plagued by bad luck throughout the fall campaign. In August, President Eisenhower made televised comments that hurt Nixon. In addition, Nixon had to cease campaigning for two weeks early in the campaign to recover from a knee injury. Despite this delay in campaigning, he refused to abandon his pledge to visit all 50 states. Thus, he wound up wasting time visiting states that he had no chance of winning and states that had few electoral votes.

Kennedy benefited from his selection of Johnson as his running mate. Johnson vigorously campaigned for Kennedy and was instrumental in helping to carry several Southern states. On the other hand, Nixon's running mate ran a lethargic campaign and made additional mistakes which hurt Nixon.

The Debates

The key turning point of the campaign were the four Kennedy-Nixon debates. These were the first presidential debates held on television, and they attracted enormous publicity. In the first debate, Nixon looked pale, sickly, underweight, and tired as a result of his hospital stay. Kennedy, by contrast, appeared strong, confident, and relaxed during the debate.

Kennedy-Nixon Debate

The turning point in the 1960 campaign was the debates. Nixon's poor appearance in the first debate made many believe that Kennedy had won.

An estimated 70 million viewers watched the first debate. People who watched the debate on television overwhelmingly believed Kennedy had won, while radio listeners (a smaller audience) believed Nixon had won. After it had ended, polls showed Kennedy moving into a slight lead over Nixon. For the remaining three debates, Nixon appeared more forceful than his initial appearance. However, up to 20 million fewer viewers watched the three remaining debates.

Campaign Issues: Religion and Civil Rights

A key factor that hurt Kennedy in his campaign was the widespread prejudice against his Roman Catholic religion.The religious issue was so significant that Kennedy made a speech promising to respect the separation of church and state and to not allow Catholic officials to dictate public policy to him.

In the south, the central issue in the 1960 election was the pro-civil rights stances of both Kennedy and Nixon. Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr., the civil-rights leader, was arrested in Georgia while leading a civil rights march. While Nixon refused to become involved in the incident, Kennedy placed calls to local political authorities. As a result, Kennedy received favorable publicity in the black community.

Results of the Election

The election on November 8, 1960, remains one of the most famous election nights in American history. In the national popular vote, Kennedy beat Nixon by just one tenth of one percentage point (0.1%)—the closest popular-vote margin of the 20th century. In the Electoral College, Kennedy's victory was larger, as he took 303 electoral votes to Nixon's 219 (269 were needed to win).

Post-Election Controversy

Many Republicans, including Nixon and Eisenhower, believed that Kennedy had benefited from vote fraud, especially in the states of Texas, where Kennedy's running mate Johnson was Senator, and Illinois. Nixon's campaign staff urged him to pursue recounts and challenge the validity of Kennedy's victory in several states. However, in a speech three days after the election, Nixon stated that he would not contest the election.