After World War I, manufacturing companies faced hard times as they attempted to convert from wartime production of weapons and planes to peacetime manufacturing of goods. However, the pro-business policies put in place by President Warren G. Harding and Vice President Calvin Coolidge, who became president following Harding’s death in 1923, fostered the growth of U.S. companies. These businesses soon flourished in part due to a raise in tariff rates from 27% to 41% under the Underwood-Simmons Tariff. In addition to employing pro-business acts and policies, Coolidge went against his own beliefs about staying out of international relations and signed an international treaty intended to avoid war in order to promote a peace that would aid American business ventures.

Setting Up Shop Abroad

As they had before the war, many major American companies in the 1920s set up shop in various foreign countries based on the available resources need to produce their wares. American meat packers moved to Argentina; fruit growers established themselves in Costa Rica, Honduras and Guatemala; sugar plantation owners went to Cuba; rubber plantation owners to the Philippines, Sumatra, and Malaya; copper corporations to Chile; and oil companies to Mexico and Venezuela.

Unfortunately, economic inequalities within the world's economic system encouraged policies that served to exploit, rather than improve, these regions for the growth and success of American companies. Thus began an era of economic neo-colonialism in which natural resources were heavily extracted from developing countries in the Global South to bolster the prosperity of wealthy countries in the Global North.

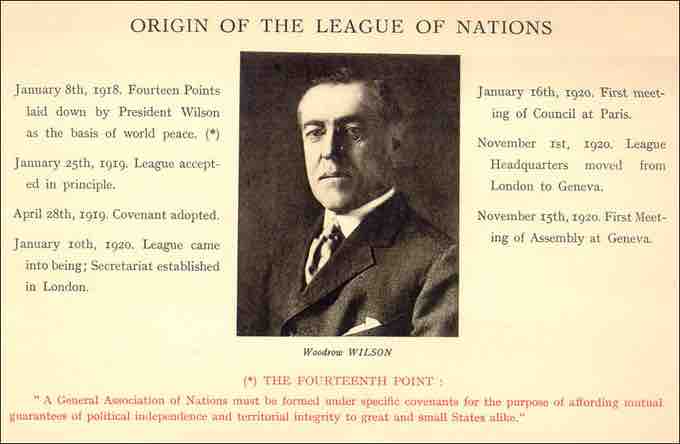

League of Nations and World Court

Although not an isolationist, President Coolidge was reluctant to enter into foreign alliances after America suffered dramatically to help win what was essentially a European war. Coolidge saw the landslide Republican victory in the presidential election of 1920 as a rejection of the Democratic Wilsonian push for the United States to join the League of Nations. While not completely opposed to the idea himself, Coolidge believed the league, as then constituted, did not serve American interests and he would not advocate U.S. membership. Coolidge also refused to recognize the Soviet Union, continuing the policy of the previous administration.

Coolidge spoke publicly in favor of America joining the Permanent Court of International Justice, also known as the World Court, but insisted the United States should not be bound by advisory decisions handed down by foreign powers. The U.S. Senate eventually approved a measure to join the court, with reservations, in 1926. While the League of Nations accepted the reservations, it suggested some modifications upon which the Senate failed to act and the U.S. ultimately never joined the World Court.

Detail from a League of Nations poster, circa 1920

President Calvin Coolidge did not advocate U.S. membership in the League of Nations.

Foreign Policy in the Americas

Coolidge continued American support for the elected government of Mexico against opposition rebels, lifting the arms embargo on that country and sending his close friend Dwight Morrow to Mexico as the American ambassador. Coolidge represented the United States at the Pan American Conference in Havana, Cuba, making him the only sitting president to visit the country. The American occupation of Nicaragua and Haiti continued under his administration, although Coolidge withdrew American troops from the Dominican Republic in 1924.

Kellog-Briand Pact

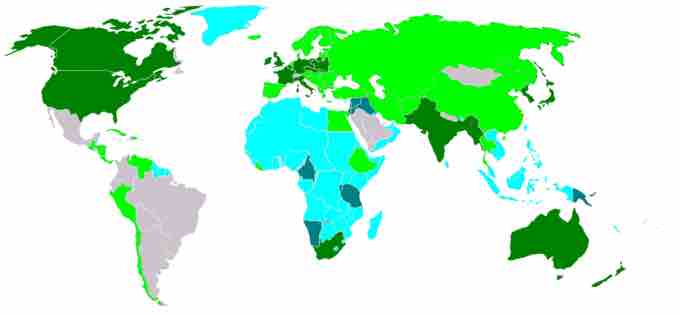

Coolidge's best-known foreign policy initiative was the Kellogg–Briand Pact of 1928, named for Coolidge's Secretary of State, Frank B. Kellogg, and French Foreign Minister Aristide Briand. The treaty, ratified in 1929, committed signatories including the United States, the United Kingdom, France, Germany, Italy, and Japan to "renounce war, as an instrument of national policy in their relations with one another." Although the treaty failed to prevent an even greater global conflict involving all of the major signatories beginning just 1o years later, it nonetheless provided the founding principle for international law after the end of World War II.

Parties to the Kellogg-Briand Pact

This map indicates the nations that were party to the Kellog-Briand Pact of 1928 and their degree of involvement in the treaty. Dark Green = original signatories; Green = subsequent adherents; Light Blue = territories of parties; Dark Blue = League of Nations mandates administered by parties.