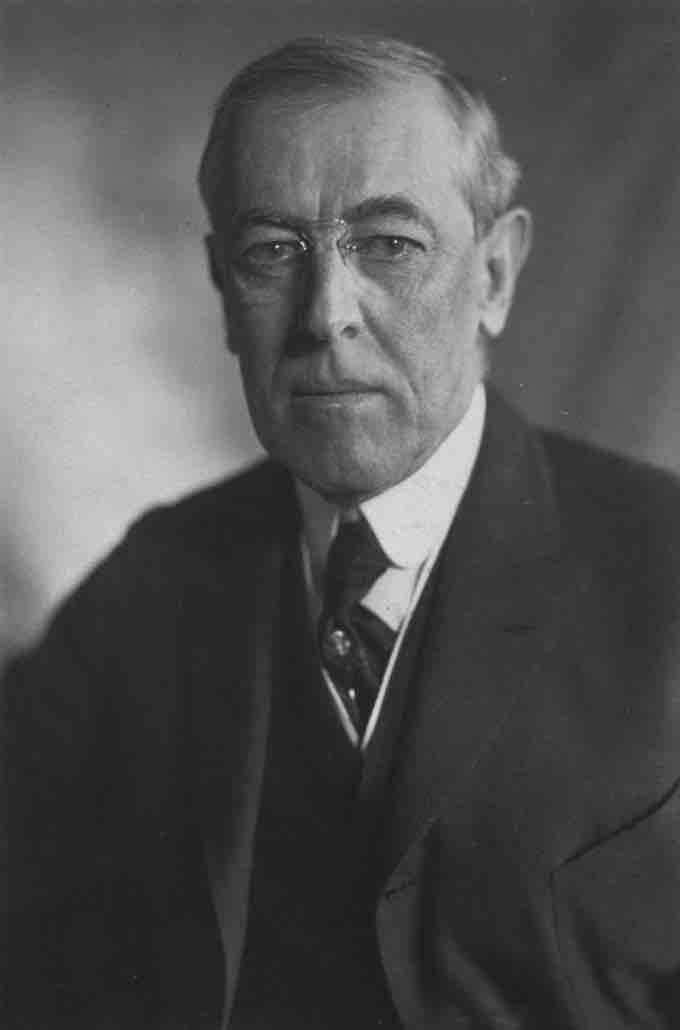

Woodrow Wilson: Introduction

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856 – February 3, 1924) was the twenty-eighth US president and a leader of the American Progressive Movement. Running against Progressive ("Bull Moose") Party candidate Theodore Roosevelt and Republican candidate William Howard Taft, Wilson was elected president as a Democrat with a wide margin of victory in 1912.

Election of 1912

During Taft's administration, a rift grew between Roosevelt and Taft as they became the leaders of the Republican Party's two wings: the progressives, led by Roosevelt, and the conservatives, led by Taft. The progressive Republicans favored restrictions on the employment of women and children, ecological conservation, and were more sympathetic toward labor unions.

The results of the 1910 elections made it clear to Taft that Roosevelt no longer supported his presidency, and that he might even contend for the party nomination in 1912. To the surprise of observers who thought Roosevelt had unstoppable momentum, Taft was determined to not step aside for the popular ex-President, despite this diminished support. Taft acknowledged this, saying, "the longer I am President, the less of a party man I seem to become." In February, 1912, Roosevelt declared his candidacy for the Republican nomination. In response, Taft soon decided that he would focus on canvassing for delegates and not attempt at the outset to confront Roosevelt. As Roosevelt became more radical in his progressivism, Taft was hardened in his resolve to achieve re-nomination; ultimately he outmaneuvered Roosevelt, regained control of the GOP convention, and won the nomination.

As a result of Taft's success in securing the nomination, Roosevelt and his group of disgruntled party members officially split from the party to create the Progressive Party (or "Bull Moose Party") ticket, splitting the Republican vote in the 1912 election. Taft thought that, despite probable defeat, the Republican party had been preserved as "the defender of conservative government and conservative institutions."

However Woodrow Wilson, the Democratic nominee, was elected with 41% of the popular vote, Roosevelt 27%, and Taft, 25%. Taft won a mere eight electoral votes (in Utah and Vermont) marking his defeat as the worst in American history of an incumbent President seeking re-election. In part, Taft's defeat resulted from his weakness as a campaigner. Furthermore, Taft's indifference towards the press (he once sought to legislatively abolish the press' reduced tariff rates on print paper and wood pulp) meant that he was an unpopular figure for political journalists and commentators, and the press seized the opportunity to lash out at Taft during the election.

The split in the Republican vote made it possible for Wilson to carry a number of states that had been reliably Republican for decades. For the first time since 1852, a majority of the New England states were carried by a Democrat. In fact, Wilson was the first Democratic presidential candidate ever to carry the state of Massachusetts (whereas Rhode Island and Maine had not been carried by a Democrat since 1852). On the West coast, Oregon had not been carried by a Democrat since 1868. The split in the Republican vote resulted in the weakest Republican effort in history.

First Term

In his inaugural address Wilson reiterated his agenda for lower tariffs and banking reform, as well as aggressive trust and labor legislation.

In his first term as President, Wilson persuaded a Democratic Congress to pass major progressive reforms: the Federal Reserve Act, Federal Trade Commission Act, the Clayton Antitrust Act, the Federal Farm Loan Act, and an income tax. He also had Congress pass the Adamson Act, which imposed an 8-hour workday for railroad workers.

Wilson, the only Democrat besides Grover Cleveland to be elected president since 1856 and the first Southerner since 1848, recognized his Party's need for high-level federal patronage. Wilson worked closely with Southern Democrats. In Wilson's first month in office, Postmaster General Albert S. Burleson brought up the issue of segregating workplaces in a cabinet meeting and urged the president to establish it across the government, in restrooms, cafeterias and work spaces. Treasury Secretary William G. McAdoo also permitted lower-level officials to racially segregate employees in the workplaces of those departments.

In an early foreign policy matter, Wilson responded to an angry protest by the Japanese when the state of California proposed legislation that excluded Japanese people from land ownership in the state. Wilson was reticent to assert federal supremacy over the state's legislation. There was talk of war and some argument within the cabinet for a show of naval force, which Wilson rejected; after diplomatic exchanges the scare subsided.

In implementing economic policy, Wilson had to transcend the sharply opposing policy views of the Southern and agrarian wing of the Democratic Party led by Bryan, and the pro-business and Northern wing led by urban political bosses—Tammany in New York, Sullivan in Chicago, and Smith and Nugent in Newark. In his Columbia University lectures of 1907, Wilson had said "the whole art of statesmanship is the art of bringing the several parts of government into effective cooperation for the accomplishment of particular common objects." As he took up the first item of his "New Freedom" agenda—lowering the tariffs—he quite adroitly applied this artistry. With large Democratic majorities in Congress and a healthy economy, Wilson seized the opportunity to achieve his agenda. Wilson also made quick work of realizing his pledges to beef up antitrust regulation and to bring reform to banking and currency matters.

Second Term

Narrowly re-elected in 1916, Wilson centered his second term on World War I and the subsequent peace treaty negotiations in Paris. He based his re-election campaign around the slogan, "He kept us out of war," but was soon forced to abandoned US neutrality. In early 1917, Germany began unrestricted submarine warfare against American ships. During the war, Wilson focused on diplomacy and financial considerations, leaving the waging of the war itself primarily in the hands of the Army. On the home front in 1917, he began the United States' first draft since the American Civil War, raised billions of dollars in war funding through Liberty Bonds, set up the War Industries Board, promoted labor union cooperation, supervised agriculture and food production through the Lever Act, took over control of the railroads, and suppressed anti-war movements.

In the late stages of the war, Wilson took personal control of negotiations with Germany, including the armistice. In 1918, he issued his Fourteen Points, his view of a post-war world that could avoid another terrible conflict. In 1919, he went to Paris to create the League of Nations and shape the Treaty of Versailles, with special attention on creating new nations out of defunct empires. In 1919, Wilson engaged in an intense fight with Henry Cabot Lodge and the Republican-controlled Senate over giving the League of Nations power to force the U.S. into a war. Wilson collapsed with a debilitating stroke that rendered him ineffective until he left office in March 1921. The Senate rejected the Treaty of Versailles, the US never joined the League, and the Republicans won a landslide in 1920 by denouncing Wilson's policies.

Wilson was also a highly effective partisan campaigner as well as legislative strategist. A Presbyterian of deep religious faith, Wilson appealed to a gospel of service and infused a profound sense of moralism into his idealistic internationalism, now referred to as "Wilsonian." Wilsonianism called for the United States to enter the world arena to fight for democracy and has remained a contentious position in American foreign policy. For his sponsorship of the League of Nations, Wilson was awarded the 1919 Nobel Peace Prize. However, Wilson remained opposed to African American Civil Rights and imposed a segregation policy in most Washington D.C. federal offices that was not overturned until President Harry S. Truman.

Woodrow Wilson

28th President of the United States