Background

The Pinchot-Ballinger Controversy, also known as the "Ballinger Affair," was a dispute between U.S. Forest Service Chief Gifford Pinchot and U.S. Secretary of the Interior Richard Achilles Ballinger. The dispute contributed to the split of the Republican Party before the 1912 presidential election and helped to define the U.S. conservation movement in the early twentieth century.

Theodore Roosevelt was an ardent conservationist, assisted in this by like-minded appointees, including Interior Secretary James R. Garfield and Chief Forester Gifford Pinchot. Taft agreed on the need for conservation, but felt it should be accomplished by legislation rather than by executive order. He did not retain Garfield, an Ohioan, as secretary, choosing instead a westerner, former Seattle mayor Richard A. Ballinger. Roosevelt was surprised at the replacement, believing that Taft had promised to keep Garfield, and this change was one of the events that caused Roosevelt to realize that Taft would choose different policies. Ballinger's appointment was a disappointment to conservationists, who interpreted the replacement of Garfield as a break with the conservationist policies of the Roosevelt administration. Indeed, within weeks of taking office, Ballinger reversed some of Garfield's policies, restoring 3 million acres to private use.

Allegations by Pinchot and Glavis

By July 1909, Gifford Pinchot, who had been appointed by William McKinley to head the USDA Division of Forestry in 1898, was convinced that Ballinger intended to, "stop the conservation movement" started under President Roosevelt. In August, speaking at the annual meeting of the National Irrigation Congress, Pinchot accused Ballinger of siding with private trusts in water-power issues. Pinchot arranged a meeting between Taft and Louis Glavis, chief of the Portland, Oregon, Field Division of the General Land Office (GLO). Glavis met with the president at Taft's summer retreat in Beverly, Massachusetts, and presented him with a 50-page report accusing Ballinger of an improper interest in his handling of coalfield claims in Alaska.

Glavis claimed that Ballinger, first as commissioner of the General Land Office, and then as secretary of the Interior, had interfered with investigations of coal claim purchases made by Clarence Cunningham of Idaho. In 1907, Cunningham had partnered with the Morgan-Guggenheim "Alaska Syndicate" to develop coal interests in Alaska. The GLO had launched an antitrust investigation, headed by Glavis. Ballinger, then head of the GLO, rejected Glavis's findings and removed him from the investigation. In 1908, Ballinger stepped down from the GLO, and took up a private law practice in Seattle. Cunningham became a client.

Convinced that Ballinger, now head of the U.S. Department of Interior, had a personal interest in obstructing an investigation of the Cunningham case, Glavis had sought support from the U.S. Forest Service, whose jurisdiction over the Chugach National Forest included several of the Cunningham claims. He received a sympathetic response from Alexander Shaw, Overton Price, and Pinchot, who had helped Glavis prepare the presentation for Taft.

Consequences

Taft consulted with Attorney General George Wickersham before issuing a public letter in September, exonerating Ballinger and authorizing the dismissal of Glavis on grounds of insubordination. At the same time, Taft tried to amicably resolve the problem with Pinchot and affirm his administration's pro-conservation stance. In response, Glavis took his case to the press. In November, Collier's Weekly published an article that elaborated on his allegations, titled "The Whitewashing of Ballinger: Are the Guggenheims in Charge of the Department of the Interior?" In January 1910, Pinchot sent an open letter to Senator Jonathan Dolliver, who read it into the congressional record. In this letter, Pinchot praised Glavis as a "patriot," openly rebuked Taft, and asked for congressional hearings into the propriety of Ballinger's dealings. Pinchot was promptly fired, but from January to May, the U.S. House of Representatives held hearings on Ballinger. After this congressional investigation, Ballinger was cleared of any wrongdoing, but some continued to criticize him for favoring private enterprise and exploitation over conservationism.

During Taft's administration, a rift grew between Roosevelt and Taft as they became the leaders of the Republican Party's two wings: the Progressives, led by Roosevelt, and the Conservatives, led by Taft. By 1910, the split between the two wings of the Republican Party was deep, and this, in turn, caused Roosevelt and Taft to turn against each other, despite their personal friendship. The Ballinger-Pinchot Controversy caused Progressives and Roosevelt loyalists to feel that Taft had turned his back on Roosevelt's agenda. Pinchot's dismissal alienated many Progressives within the Republican Party and drove a wedge between Taft and Roosevelt, which eventually led to the split of the Republican Party in the 1912 presidential election.

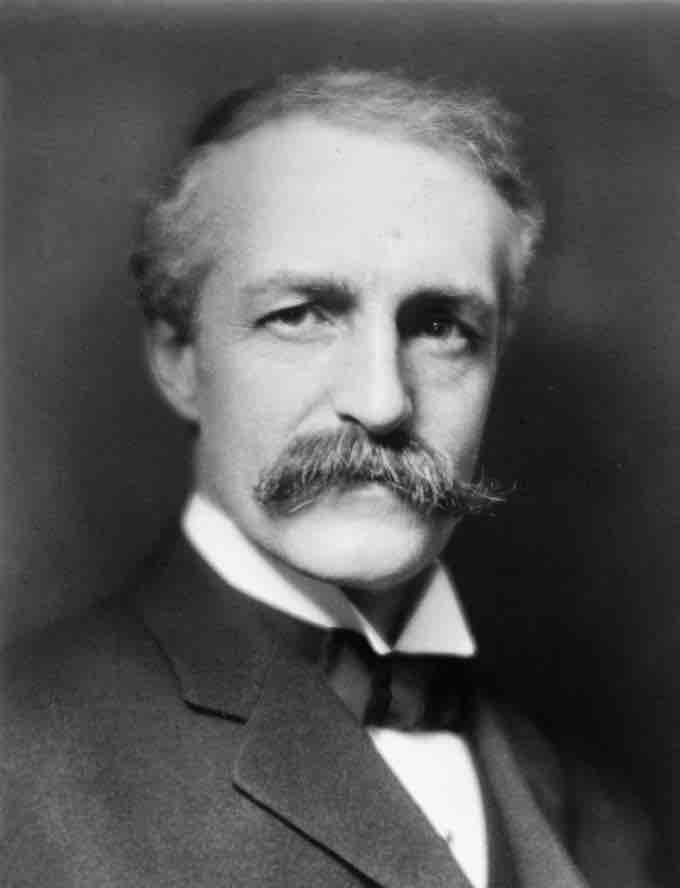

Gifford Pinchot

The firing of Pinchot—a close friend of Teddy Roosevelt's—alienated many Progressives within the Republican Party and drove a wedge between Taft and Roosevelt, leading to the split of the Republican Party in the 1912 presidential election.

"For Auld Lang Syne"

This cartoon shows Taft and Roosevelt, who were political enemies in 1912.