Background

During Reconstruction, high tariffs were the norm as the Republican Party maintained power and the Southern Democrats were restricted from office. The Republican high-tariff advocates appealed to farmers with the theme that high-wage factory workers would pay premium prices for foodstuffs. This was the "home market" idea, and it won over most farmers in the Northeast. However, it had little relevance to the southern and western farmers who exported most of their cotton, tobacco, and wheat.

Thanks to such tariffs, American industry and agriculture—apart from wool—had become the most efficient in the world by the 1880s as they took the lead in the Industrial Revolution. Hence, throughout the early twentieth century, most American manufacturers and union workers demanded the high tariff be maintained.

Tariffs remained a significant political issue during presidential elections and were often a source of contention between Democrats and Republicans. Democrats campaigned energetically against tariffs, especially the high McKinley Tariff of 1890. In 1892, Democrat Grover Cleveland was elected to the presidency, and much of his campaign platform focused on lowering the tariff. While in office, Cleveland attempted to follow through with his campaign promise with limited success. For instance, the Wilson-Gorman Tariff Act of 1894 did lower overall rates, but contained so many concessions to protectionism that Cleveland refused to sign it. In 1896, Republican McKinley campaigned heavily on the tariff issue, claiming that it was a positive solution to economic recession. Promising protection and prosperity to every economic sector, McKinley won, and the Republicans rushed through the Dingley Act in 1897, boosting rates again, while Democrats continued to argue that high rates enabled trusts to operate and led to higher consumer prices.

Taft and Tariff Reform

During Taft's election campaign in 1908, Republicans promised to lower unpopular tariffs on U.S. imports. Industries and businesses supported this high tariff, because it enabled them to compete in the world market. However, small farmers, laborers, and manufacturers resented the tariff, because it affected their exports to foreign countries. Once elected, Taft called a special session of Congress in 1909 to discuss lowering the tariff. Senator Payne proposed a bill that lowered the tariff on many imported goods. However, Congress accepted an alternative bill, proposed by Nelson Aldrich, which lowered the tariff on only a few imported items and increased it on many other products. This met with severe opposition from a faction of Republicans in the Senate. In the end, Congress adopted the Payne-Aldrich Tariff Act, which lowered 650 tariffs, raised 220 tariffs, and left 1,150 tariffs untouched. The act was signed enthusiastically by Taft in 1909, who believed that the compromise would preserve party unity.

Although the Payne-Aldrich Tariff Act did very little to affect the current status of tariffs, it angered many Democrats, Progressives, and Progressive Republicans because it did not solve the tariff issue. Taft's public support of the bill, instead of preserving party unity, further split the Republicans. Roosevelt in particular criticized Taft over the Payne-Aldrich Tariff Act, and led a faction of Progressive Republicans away from Taft's conservative Republicans. This group of Progressive Republicans eventually formed the Bull Moose Party, which selected Roosevelt as its presidential nominee in the 1912 election. Meanwhile, unified in their commitment to lowering the tariff, Democrats enjoyed rising public popularity during Taft's presidency.

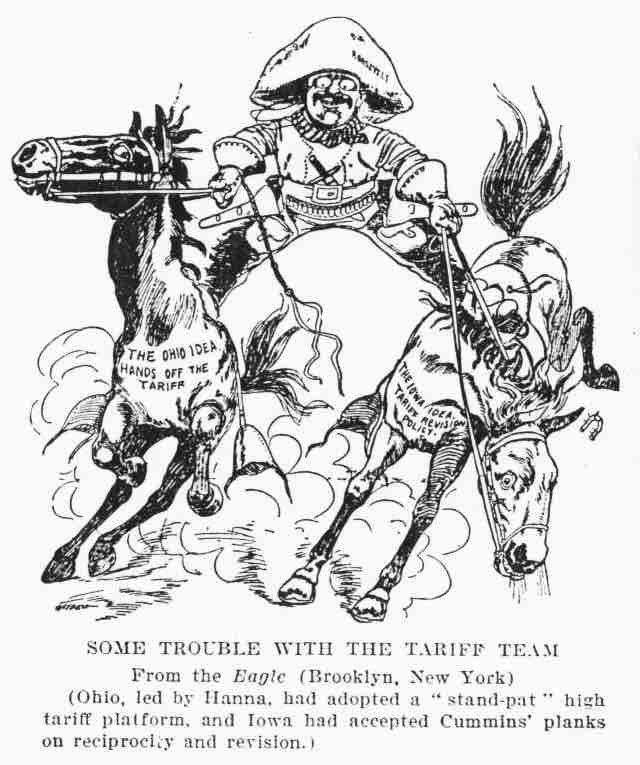

"Some Trouble with the Tariff Team"

In this 1901 editorial cartoon, President Teddy Roosevelt watches the GOP team pull apart on tariff issue.