Civil Rights vs. "Law and Order"

The Nixon administration did not prioritize civil rights to the extent of the previous Kennedy and Johnson administrations. Public support for civil rights had peaked in the mid-1960's, galvanized by Martin Luther King's leadership and media coverage of overt repression in the South. However, violent urban protests, which first broke out in the summer of 1965 and recurred occasionally for the rest of the decade, sparked a conservative backlash in the public opinion of white citizens. A majority of fearful white Americans began to prioritize "law and order" over the advancements of civil rights. Nixon sought a politically viable stance on civil rights, promising a return to law and order while simultaneously offering improved educational and business opportunities to African Americans. Nixon's presidency thus saw the continuation of some of the civil rights progress set in motion by previous administrations, even as he courted conservative voters.

Public School Integration

The Nixon years witnessed the first large-scale integration of public schools in the South. Nixon sought a middle way between the segregationists (those supporting school segregation) and liberal Democrats who supported integration. He supported integration in principle, but he was opposed the use of busing (using bus systems to transport African American students to previously all-white school districts and vice versa) to force integration. Nixon's goals were partly political: he hoped to retain the support of southern conservatives, many of whom had voted Republican for the first time in the 1964 and 1968 elections. These southern voters had been alienated from the Democratic party by Kennedy and Johnson's civil rights legislation; to capitalize on this, Nixon tried to get the issue of desegregation out of the way with as little damage as possible.

Soon after Nixon's inauguration, he appointed Vice President Spiro Agnew to lead a task force to work with local leaders—both white and black—to form a plan for integrating local schools. Agnew had little interest in the work, so most of it was done by Labor Secretary George Shultz. The task force's plan made federal aid and official meetings with President Nixon available as rewards for school committees who complied with desegregation plans. By September of 1970, fewer than 10% of African American children were attending segregated schools. Many whites reacted angrily to busing and forced integration, sometimes protesting and rioting. Nixon opposed busing personally but enforced court orders requiring its use.

Affirmative Action

In addition to desegregating public schools, Nixon implemented the Philadelphia Plan in 1970—the first significant federal affirmative action program. The Philadelphia Plan was based on an earlier plan developed in 1967 by the Office of Federal Contract Compliance and the Philadelphia Federal Executive Board. Executive Order 11246 put the Philadelphia Plan into effect, and Department of Labor Assistant Secretary for Wage and Labor Standards Arthur Fletcher was in charge of implementing it.

The plan required government contractors in Philadelphia to hire minority workers, meeting certain hiring goals by specified dates. It was intended to combat institutionalized discrimination in specific skilled building trade unions that prevented equitable hiring of African Americans. The plan was quickly extended to other cities. The Philadelphia Plan was challenged in the lawsuit Contractors' Association of Eastern Pennsylvania v. Shultz, et al, but the court upheld the plan and the Supreme Court refused to hear an appeal.

Equal Rights Amendment

Nixon's civil rights efforts also included his endorsement of the Equal Rights Ammendment (ERA). The ERA was a proposed amendment to the United States Constitution which outlawed any form of legal discrimination based on sex. In 1972, it passed both houses of Congress and went to the state legislatures for ratification. The ERA failed to receive the requisite number of ratifications before the final deadline mandated by Congress of June 30, 1982 expired, so it was not adopted.

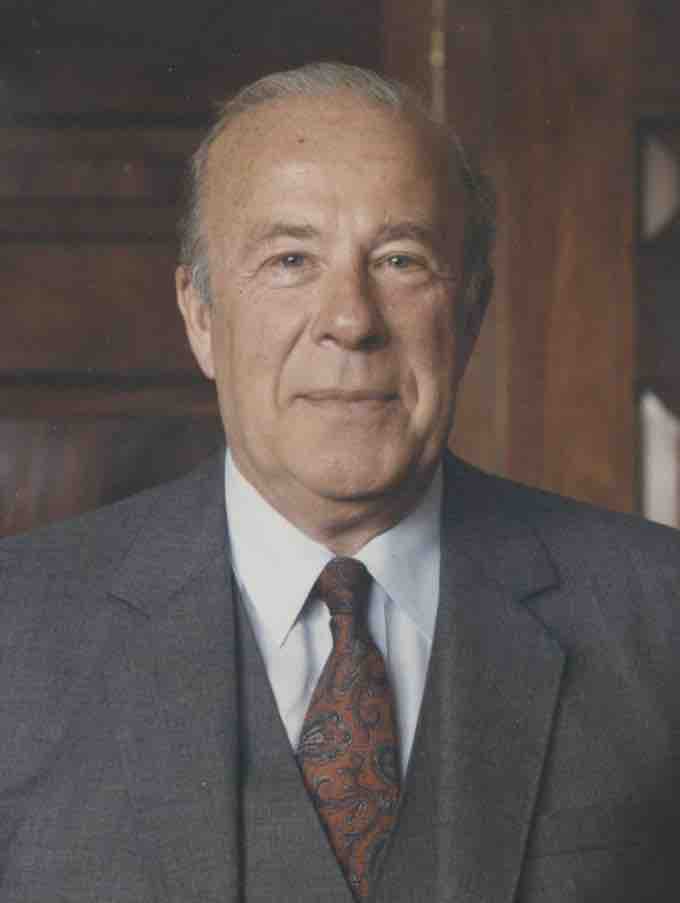

George Shultz, President Nixon's Secretary of Labor

Secretary Shultz was influential in Nixon's school integration and affirmative action policies. Shultz would later serve as Secretary of State under Ronald Reagan.