British Patriotism, British Identity

The Glorious Revolution

In the aftermath of the Glorious Revolution, many British intellectuals reevaluated the identity of Britain as a nation and empire. When James II attempted to impose taxes without parliamentary approval and converted to Catholicism, Parliament offered the crown to Mary and William of Orange, which affirmed the supremacy of Parliament and Protestantism over Monarchy and Catholicism, and was perceived as authoritarian. For many British subjects, the aftermath of the Glorious Revolution ushered in a period of pride and reevaluation of national identity.

Enlightenment Thinkers

The events of the Glorious Revolution reaffirmed that Parliament was the highest authority in the nation, and more significantly, that the monarch could not rule without parliamentary consent and approval. Furthermore, as emphasized by 17th-century Enlightenment thinkers, Parliament was considered the least corrupt form of government because governments derived existence from the consent of the governed, and the elected representative body was answerable to its constituents.

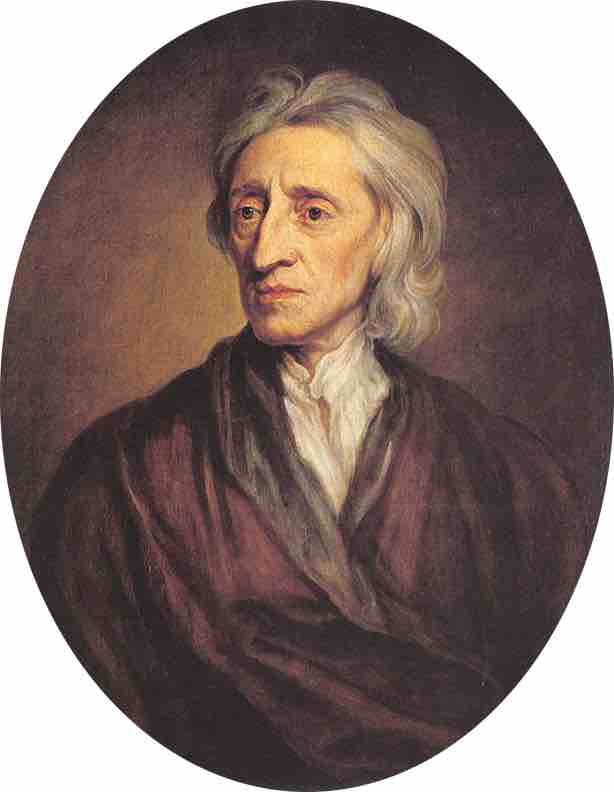

The highly intellectual Enlightenment was dominated by philosophers who opposed the absolute rule of the monarchs of their day and instead emphasized the equality of all individuals and the idea that governments derived their existence from the consent of the governed. For instance, in 1690, John Locke (one of the fathers of the English Enlightenment) wrote that all people have fundamental natural rights to "life, liberty, and property" and that governments were created in order to protect these rights. If they did not, according to Locke, the people had a right to alter or abolish their government.

John Locke

John Locke is often credited for the creation of liberalism as a philosophical tradition.

The Rights of Englishmen

The ensuing language of the "rights of Englishmen" that dominated 17th- and 18th-century discourse in Britain and the North American colonies thus gave rise to a sense of national identity that revolved around the belief that (white) men held certain "inalienable" rights of liberty and property that could not be violated by any political power. For instance, even though most British males did not meet the property ownership requirements for suffrage, the representative traits of Parliament were praised by many intellectual contemporaries who believed that such a political system best embodied the "social contract" that men used to create civilization and political authority.

Anglo-American Colonial Identity and Civic Duty

While British intellectuals and leaders formulated a concept of "British identity" in the 17th and 18th centuries, Anglo-American colonists in North America also developed an identity that drew heavily on both British liberalism and the colonial American experience. Unlike the colonial mother state of Britain, Anglo-American colonial representative government was an intensely localized process where elections and participation in assemblies and court trials were a fundamental aspect of proper civic life. For instance, public colonial elections were events in which all free white males were expected to participate in order to demonstrate proper civic pride. Public office attracted many talented young men of ambition to civil service, and colonial North American suffrage was one of the most widespread in the world at that time, with every man who owned a certain amount of property allowed to vote. The widespread availability of property in the 13 colonies provided most white males with the opportunity to own some amount of property; therefore, while fewer than 1% of British men could vote, a majority of white American men were eligible to vote and run for office.

Participation in public and political life was remarkably widespread, at least for white men and especially when compared with the more rigid, elitist systems in Europe. American colonial politics revolved around the notion of public civic life and responsibility, an ideology that included:

- Civic duty: Citizens have the responsibility to understand and support the government, participate in elections, pay taxes, and perform military service.

- United opposition to political corruption.

- Democracy: The government is answerable to citizens, who may change the representatives through elections.

- Equality before the law: The laws should attach no special privilege to any citizen, and government officials and wealthier citizens are also subject to the law. This markedly only applied to equality for white men and excluded slaves, American Indians, and women.

- Freedom of religion: The government can neither support nor suppress religion.

- Freedom of speech: The government cannot restrict the citizen's right to criticize authority or voice opposition to the government.

Most of these principles evolved out of centuries-long colonial tradition (beginning with the Pilgrims fleeing religious restriction in England) rather than any collective, intended ambition to create a democratic society. By the mid-18th century, these civic ideals had been enshrined in the American colonial political system as a fundamental foundation of political rights and liberties. While inspired by inspired by British values, the political system was also distinct from them. With the building conflict with Britain in the 1760s and 1770s, these principles (particularly that the government is answerable to citizens and political representation is a requisite for implementing new taxes) were often invoked by colonists as justification for boycotting British goods and other forms of resistance that led to the American Revolution.