Early in the war, the Confederate economy relied mostly on tariffs on imports and taxes on exports. The Confederate economy also relied on voluntary donations of coins and bullion from private individuals in support of the Confederate cause; these were initially quite substantial, but became scarce by the end of 1861. A small "war-tax" was enacted in August 1861, but proved to be politically unpopular among Southern Democrats and difficult to collect.

The Confederate government desperately sought to secure international recognition of the Confederacy as a nation and gain European allies. The Confederate government hoped to force diplomatic recognition of the Confederacy by starving Europe of cotton. In 1861, Southern planters agreed to a self-imposed embargo on cotton exports. Cotton was stored in warehouses and used to prop up Confederate war bonds sold in Europe. Throughout the war, the South clung to the notion that the Confederacy would be able to capitalize on its cotton monopoly.

This embargo was effective at first, creating an immediate source of income from the valuable cotton-backed bonds, shutting down hundreds of textile factories, and putting thousands of people in Europe out of work. However, the embargo became a loss for the Confederacy when the British did not cave in to its demands, choosing instead to import cotton from Egypt and India in 1862.

The self-inflicted damage resulting from the embargo was exacerbated by the blockade of Southern ports by the Union Navy, beginning in 1861. The Union blockade greatly diminished the revenue from taxes on international trade, and Southern cotton exports fell by 95 percent. This powerful weapon eventually ruined the Southern economy. Ordinary freighters had no reasonable hope of evading the blockade and soon stopped calling at Southern ports. The blockade largely reduced imports of food, medicine, war materials, manufactured goods, and luxury items, resulting in severe shortages and inflation.

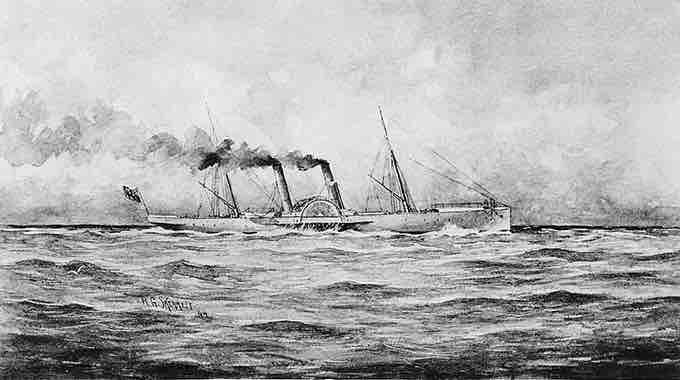

The blockade runner USS Banshee (1862), by R.G. Skerrett, 1899

The USS Banshee was among the blockade runners that attempted to evade the Union blockade of the Confederate coast.

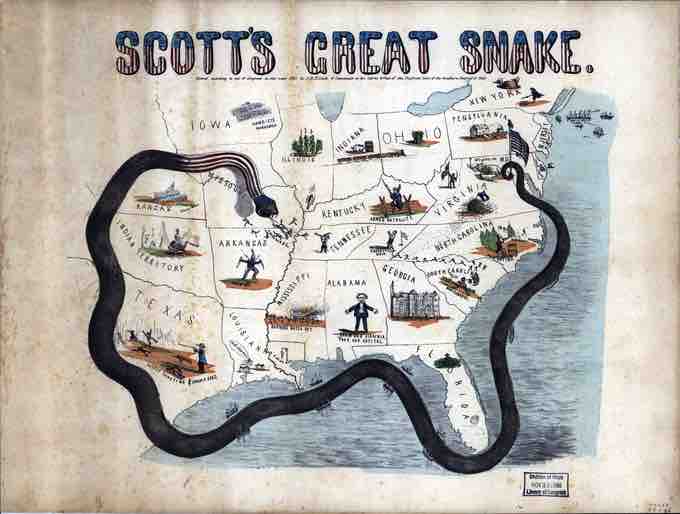

Cartoon map illustrating General Winfield Scott's plan to crush the Confederacy economically, 1861

This snake represents the Union blockade of Southern ports.

Hoping to avoid an unpopular tax increase, the Confederacy soon turned to issuing debt and printing Confederate money to finance the war. Many banks suspended specie payments at the end of 1860, and thereafter irresponsibly increased banknote issue and loans. These choices added to the general redundancy of the currency and stimulated speculation. During the course of the war, Confederate States of America dollars severely depreciated and eventually became worthless. The resulting inflation remained a problem for the Southern states throughout the remainder of the war, collapsing the South's financial infrastructure and forcing a move to a barter economy for civilians.

By 1863, the Southern economy, which was completely tied to the price of cotton, had crashed, crippling the South's ability to secure any kind of European alliance or purchase badly needed war supplies. With little revenue from taxation, and with the disastrous effects of the wholesale issue of paper money before it, the Confederate government made every effort to borrow money by issuing bonds. These bonds, however, depreciated rapidly as the economy collapsed. At the beginning of the war, the Confederate dollar was valued at 90¢ in Union dollars. By the war's end, its price had dropped to only .017¢.

Five-dollar and 100-dollar Confederate States of America banknotes

Confederate currency, widely distributed during the war, ultimately lost all value.