Prior to the Civil War, Abraham Lincoln attempted to abstain from the debate over slavery, arguing that he had no constitutional authority to intervene. As the war progressed, emancipation remained a risky political act that had little public support. Lincoln faced strong opposition from Copperhead Democrats, who demanded an immediate peace settlement with the Confederacy. Many recent immigrants in the North also opposed emancipation, viewing freed slaves as competition for scarce jobs. Within the Republican Party, however, the Radical Republicans, led by House Republican leader Thaddeus Stevens, put strong pressure on Lincoln to end slavery quickly. One of the Radicals Republicans' most persuasive arguments was that the rebel economy would be destroyed were it to lose slave labor.

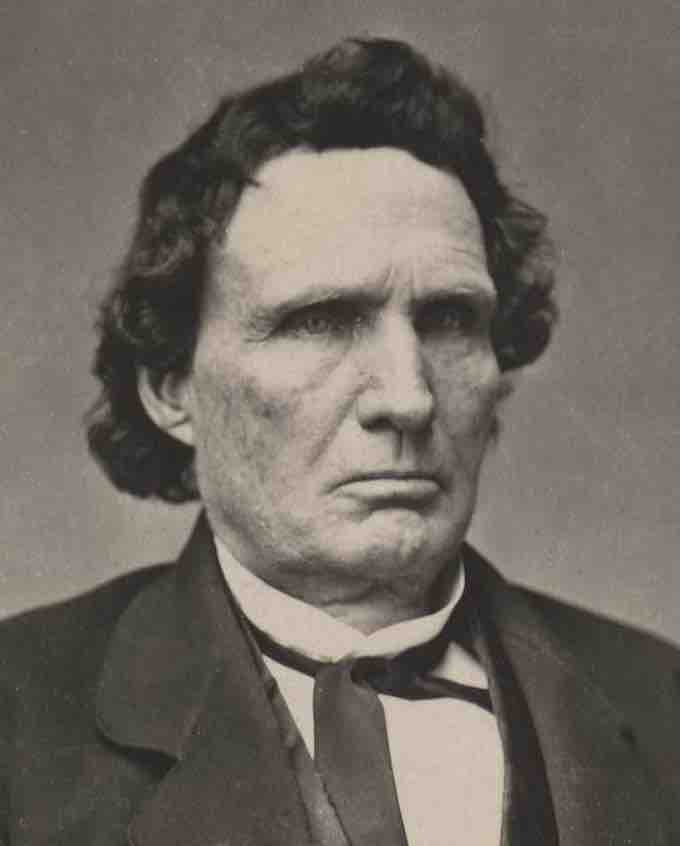

Thaddeus Stevens, ca. 1863

Stevens was a leader among the Radical Republicans, supporters of emancipation.

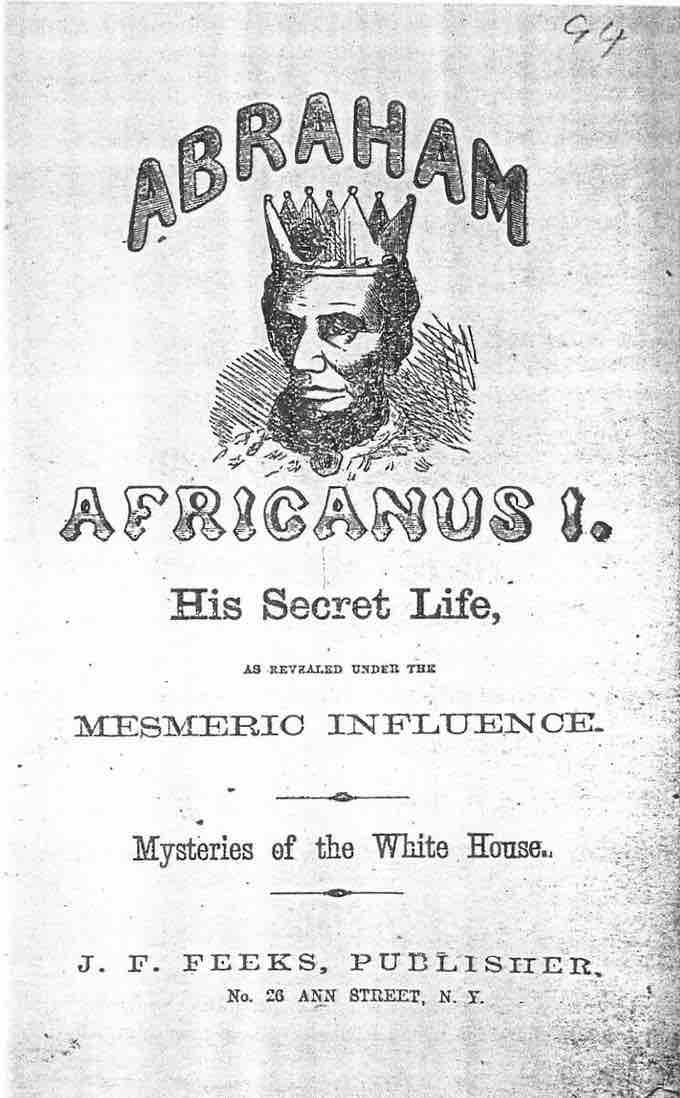

Copperhead pamphlet from 1864 mocking President Abraham Lincoln

The Copperhead Democrats strongly opposed emancipation and pressured Lincoln to make peace with the Confederacy.

Congress passed several laws between 1861 and 1863 that aided the growing movement toward emancipation. Despite his concerns that premature attempts at emancipation would weaken his support and entail the loss of crucial border states, Lincoln signed these acts into law. The first of these laws to be implemented was the First Confiscation Act of August 1861, which authorized the confiscation of any Confederate property, including slaves, by Union forces. In March 1862, Congress approved a Law Enacting an Additional Article of War, which forbade Union Army officers from returning fugitive slaves to their owners. The following month, Congress declared that the federal government would compensate slave owners who freed their slaves. Moderate Republicans accepted Lincoln's plan for gradual, compensated emancipation, which was put into effect in the District of Columbia.

In June 1862, Congress passed a Law Enacting Emancipation in the Federal Territories, and in July, passed the Second Confiscation Act, which contained provisions intended to liberate slaves held by rebels. The latter act also declared that any Confederate official, military or civilian, who did not surrender within 60 days of the act's passage would have his slaves freed.

In order to increase public support for emancipation, Lincoln strategically chose to associate the Emancipation Proclamation with the Union victory at the Battle of Antietam in September 1862. On September 22 of that year, Lincoln issued a preliminary proclamation that he would order the emancipation of all slaves within all Confederate states that did not return to Union control by January 1, 1863. When none of the states returned to the Union by that date, Lincoln honored his proclamation, and the order immediately took effect.

Predictably, the Confederates were initially outraged by the Emancipation Proclamation and used it as further justification for their rebellion. The Proclamation was also immediately denounced by Copperhead Democrats, a more extreme wing of the Northern Democratic faction of the Democratic Party that opposed the war and hoped to restore the Union peacefully via federal acceptance of the institution of slavery. Additionally, these Democrats viewed the Proclamation as an unconstitutional abuse of Presidential power. Controversy surrounding the Emancipation Proclamation, as well as military defeats suffered by the Union, caused many moderate Democrats to abandon Lincoln and join the more extreme Copperheads in the 1862 elections. Democrats gained 28 seats in the House in the 1862 election cycle, as well as the governorship of New York.

Some Copperheads advocated violent resistance to the wartime effort, which greatly increased tensions between pro-war and anti-war factions. Though no organized attacks ever materialized, sensationalist politics did give rise to the Charleston Riot in Illinois during March 1864. Many Copperhead leaders were arrested and held in military prisons without trial, sometimes for months at a time. For example, Ambrose Burnside in 1863 issued General Order Number 38 in Ohio, which made it an offense to criticize the war in any way. The order was then used to arrest a congressman from Ohio, Clement Vallandigham, when he criticized the order itself. Additionally, a number of Copperheads were accused of treason by Republicans in a series of trials that took place during 1864.

A faction within the Republican Party, called the "Radical Republicans," also opposed the war. Unlike the Copperheads, Radical Republicans were strongly against the institution of slavery and pushed for uncompensated abolition of the slaves as opposed to Lincoln’s plan to pay individuals who freed their slaves and were also loyal to the Union. For a brief time in 1864, Radical Republicans formed a new political party called the "Radical Democracy Party" with John Frémont as their presidential candidate, but the party dissolved when Frémont withdrew his candidacy. Radical Republicans were generally critical of President Lincoln, but he still appointed members of all political factions to his cabinet.