Religion played a major role in the American Revolution by offering a moral sanction for opposition to the British—an assurance to the average American that revolution was justified in the sight of God. As a recent scholar has observed, "by turning colonial resistance into a righteous cause, and by crying the message to all ranks in all parts of the colonies, ministers did the work of secular radicalism and did it better."

"Obedience to God"

This is an interpretation of the proposed design for the first seal of the United States. Benjamin Franklin suggested it, but it was ultimately not used. The caption reads: "Rebellion to Tyrants is Obedience to God." Religious beliefs were often used to justify colonial rebellion.

Ministers served the American cause in many capacities during the Revolution—as military chaplains; as scribes for committees of correspondence; and as members of state legislatures, constitutional conventions, and the Continental Congress. Some even took up arms, leading Continental Army troops in battle. The Revolution split some denominations, notably the Church of England, whose ministers were bound by oath to support the king; and the Quakers, who were traditionally pacifists. Religious practice suffered in certain places because of the absence of ministers and the destruction of churches, but in other areas, religion flourished.

The Revolution strengthened millennialist strains in American theology. At the beginning of the war, some ministers were persuaded that, with God's help, America might become "the principal Seat of the glorious Kingdom which Christ shall erect upon Earth in the latter Days." Victory over the British was taken as a sign of God's partiality for America and stimulated an outpouring of millennialist expectations—the conviction that Christ would rule on earth for 1,000 years. This attitude, combined with a groundswell of secular optimism about the future of America, helped to create the buoyant mood of the new nation that became so evident after Jefferson assumed the presidency in 1801.

Church of England

The Revolution inflicted deeper wounds on the Church of England in America than on any other denomination. This was because the English monarch was the head of the church. As a result, Church of England priests swore allegiance to the British crown at their ordination. The Book of Common Prayer offered prayers for the monarch, beseeching God "to be his defender and keeper, giving him victory over all his enemies." In 1776, these enemies were American soldiers, as well as friends and neighbors of American parishioners of the Church of England. Furthermore, loyalty to the church and to its head could be construed as treason to the American cause.

Patriotic American members of the Church of England, loathing to discard so fundamental a component of their faith as The Book of Common Prayer, revised it to conform to the political realities of the time. After the Treaty of Paris (1783) documented British recognition of American independence, the church split. The Anglican Communion was created, allowing a separated Episcopal Church of the United States that would still be in communion with the Church of England.

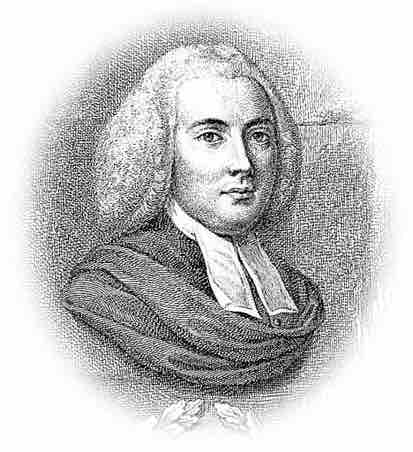

Jonathan Mayhew

Jonathan Mayhew was a noted American minister at Old West Church, Boston, Massachusetts. He is credited with coining the phrase, "No taxation without representation." Ministers were often supporters of the Patriot's cause during the Revolution.