Financing the American Revolution

Congress and the individual American colonies encountered difficulties when financing the Revolutionary War. In 1775, there was at most $12 million in gold in the colonies, not nearly enough to cover current transactions, let alone a major war. At the start of the war, neither the colonies nor the Continental Congress had an established method of raising revenue through taxation. The British made the situation worse by imposing a tight blockade on every American port, which cut off almost all imports and exports. As a result, the Continental government had to devise a number of means for financing the war.

During the Revolution

The 13 American states flourished economically at the beginning of the war. The colonies could trade freely with the West Indies and other European nations instead of just Britain. Due to the abolition of the British Navigation Acts, American merchants could now transport their goods in European and American ships rather than only British ships. British taxes on expensive wares such as tea, glass, lead, and paper were forfeited, and other taxes became cheaper. Plus, American privateering raids on British merchant ships provided more wealth for the Continental Army.

As the war went on, however, America's economic prosperity began to falter. British warships began to prey on American shipping and the increasing upkeep costs of the Continental Army meant that wealth from merchant ships decreased. The government began to rely on volunteer support from militiamen and donations from patriotic citizens. The Continental Congress also delayed payments, paid soldiers and suppliers in depreciated currency, and promised to make good on payments in arrears after the war. Indeed, in 1783, soldiers and officers were given land grants to cover the wages they had earned but had not been paid during the war.

As cash flow continued to decline, the United States had to rely on European loans to maintain the war effort; France, Spain, and the Netherlands lent the U.S. over $10 million during the war, causing major debt problems for the fledgling nation. Coin circulation also began to wane. Because of this, the U.S. began to print paper money and bills of credit to raise income. This proved unsuccessful—inflation skyrocketed and the new paper money's value diminished.

The declining value of Continental currencies hit soldiers, the poor, and individuals on fixed incomes the hardest because their wages bought less. Soldiers, for example, were already being paid in arrears due to the difficulty Congress was having financing the war, and their wages were rapidly declining in value every month. This contributed to the hardships experienced by soldiers’ families and weakened morale. Ninety percent of Americans, however, were farmers and not directly affected by inflation. Debtors also benefited from the economic situation since they were able to pay off their debts with the depreciated paper money, amounting to a discount on their previous balances.

Starting in 1776, Congress sought to raise money with loans from wealthy individuals, promising to redeem the bonds after the war. The bonds were in fact redeemed in 1791 at face value, but the scheme raised little money because Americans had little specie, and many rich merchants were supporters of the Crown. Starting in 1776, the French secretly supplied the Americans with money, gunpowder, and munitions in order to weaken their common enemy, Great Britain. When France officially entered the war in 1778, the subsidies continued, and the French government, as well as bankers in Paris and Amsterdam, loaned large sums to the American war effort. These loans were repaid in full in the 1790s.

Beginning in 1777, Congress repeatedly asked the states to provide money. But the states had no system of taxation and were of little help. By 1780, Congress was making requisitions for specific supplies of corn, beef, pork, and other necessities—an inefficient system that barely kept the army alive.

Post-Revolution

The national debt after the American Revolution fell into three categories. The first was the $12 million owed to foreigners—mostly money borrowed from France. There was general agreement to pay the foreign debts at full value. The national government owed $40 million and state governments owed $25 million to Americans who had sold food, horses, and supplies to the revolutionary forces. There were also other debts that consisted of promissory notes issued during the Revolutionary War to soldiers, merchants, and farmers who accepted these payments on the premise that the new Constitution would create a government that would pay these debts eventually.

By 1780, the United States Congress had issued over $400 million in paper money to troops. Eventually, Congress tried to stop the inflation by imposing economic reforms. These failed and only further devalued the American currency. Late in the war, Congress asked individual colonies to equip their own troops and pay upkeep for their own soldiers in the Continental Army. When the war ended, the United States had spent $37 million at the national level and $114 million at the state level.

Not until 1781, when Robert Morris was named U.S. superintendent of finance, did the national government have a strong leader in financial matters. Morris used a French loan in 1782 to set up the private Bank of North America to finance the cost of the war. Seeking greater efficiency, Morris reduced the civil list, saved money by using competitive bidding for contracts, tightened accounting procedures, and demanded the federal government's full share of money and supplies from the states. The U.S. finally solved its debt problems in the 1790s, when Alexander Hamilton established the First Bank of the United States.

Alexander Hamilton

Portrait of Alexander Hamilton, who was a key player at the Constitutional Convention and established the First Bank of the United States in the 1790s.

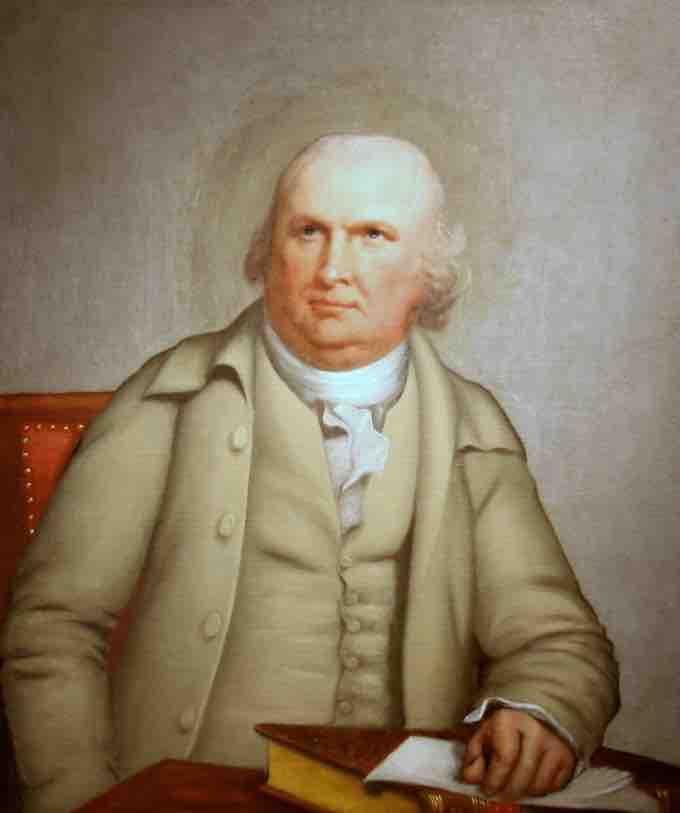

Robert Morris

Portrait of Robert Morris, who in 1781 was named superintendent of finance of the United States, giving the national government a strong leader in financial matters.