Patriot Women

In the Revolutionary Era, women were responsible for managing the domain of the household. Nonimportation and non-consumption became major weapons in the arsenal of the American resistance movement against British taxation without representation. Women played a major role in this method of defiance by denouncing silks, satins, and other imported luxuries in favor of homespun clothing, generally made in spinning and quilting bees. This sent a strong message of unity against British oppression. As a result of nonimportation, many rural communities that were previously only peripherally involved in the political movements of the day were brought "into the growing community of resistance" because of the appeal "to the traditional values" of rural life. In 1769, Christopher Gadsden made a direct appeal to colonial women, saying, "our political salvation, at this crisis, depends altogether upon the strictest economy, that the women could, with propriety, have the principal management thereof."

Housewives routinely used their purchasing power to support the patriot cause by refusing to purchase British manufactured goods for use in their homes. The tea boycott, for example, was a relatively mild way for a woman to identify herself and her household as part of the patriot war effort. While the Boston Tea Party of 1773 is the most widely recognized manifestation of this boycott, it is important to note that for years previous to that explosive action, as a political statement, patriot women had refused to consume the very same British product. The Edenton Tea Party represented one of the first coordinated and publicized political actions by women in the colonies. A total of 51 women in Edenton, North Carolina, signed an agreement officially agreeing to boycott tea and other English products and sent it to British newspapers. Similar boycotts extended to a variety of British goods with women opting to purchase or make "American" goods instead. Even though these "non-consumption boycotts" depended on national policy (formulated by men), it was women who enacted them in households.

Colonial era spinning

Many women supported the war effort by producing homespun clothing.

The Homespun Movement

In addition to boycotts of British goods, Patriot women participated in the "Homespun Movement." Instead of wearing or purchasing clothing made of imported British materials, these women continued a long tradition of weaving and spun their own cloth to make clothing for their families. In the atmosphere preceding the American Revolution, this was a politically charged action. The practices of the Homespun Movement extended beyond cloth goods. For example, Benjamin Franklin's youngest sister, Jane Mecom, was called on for her soap recipe and instructions on how to build soap-making forms. While male suppliers of such services were exempted from military service in exchange for their goods, there was no such recompense for women who did the same thing. Spinning, weaving, and sewing were seen as part of the female province; as patriots, they were expected to utilize their skills to assist the revolutionary cause without further compensation.

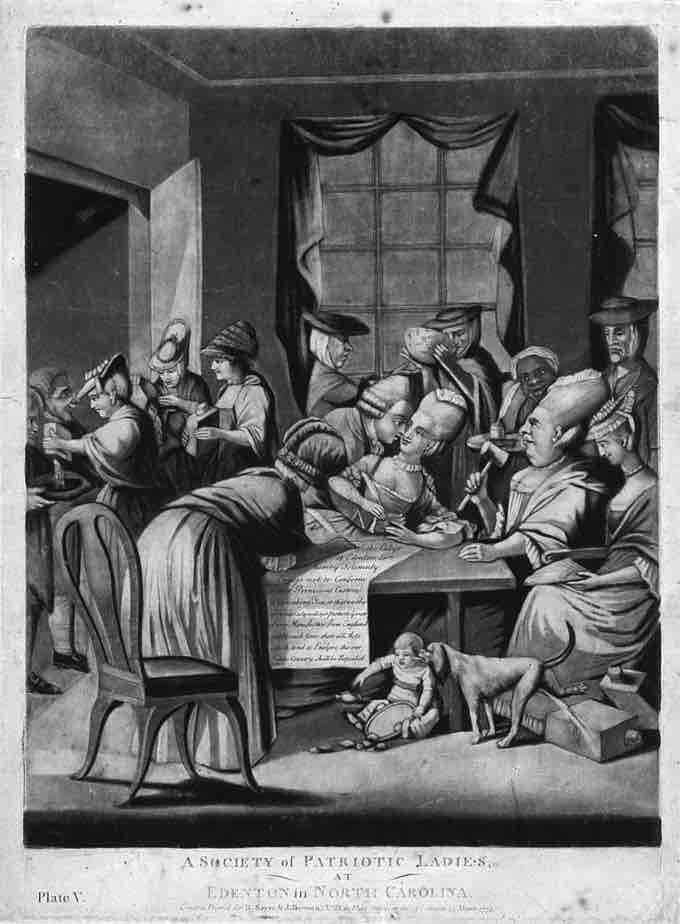

Edenton boycott

A British cartoon satirizing the Edenton Tea Party participants. The Edenton Tea Party was a women-led boycott of British products. Because women ran the household, their purchasing power was vital; boycotts such as this supported the war effort.

Women actively engaged in the economy in other ways as well. In 1778, a group of women marched down to a warehouse where it was rumored that a merchant was hoarding coffee. The women opened the warehouse, lifted out the coffee, and "confiscated" it. During the revolution, buying American products became a patriotic gesture. In addition, frugality (a lauded feminine virtue before the years of the revolution) became a political statement as households were asked to contribute to the wartime efforts. The call for women to support the war effort extended beyond contributions from the family economy of which they were in charge; women were also asked to put their homes into public service for the quartering of American soldiers and legislators as the republic took shape.

The Republican Motherhood

During the Revolutionary Era, women were increasingly placed in positions to educate future generations in the ways of republicanism. The “Republican Motherhood” came to encompass the concept that women played a role in instilling civil values and morality in their husbands and children. In many ways, the concept borrowed from Christian teachings that women should pass down religious values and morality to their children. In this way, the Republican Motherhood, though still relegating women’s contributions to the domestic sphere, raised the importance of women’s civic contributions on a national level and allowed them greater influence in the public sphere. The belief also encouraged increasing access to education for women in order ensure their abilities to instruct their children. In the longer term, the Republican Motherhood contributed to women’s involvement in abolitionism and women’s rights.

Women's Organizations

Women further helped the patriot cause through organizations such as the Ladies Association in Philadelphia, which recognized the capacity of every woman to contribute to the war effort. The women of Philadelphia collected funds to assist in the war effort, which Martha Washington then took directly to her husband, General George Washington. Other states subsequently followed the example set by founders Esther Deberdt Reed (wife of the Pennsylvania governor) and Sarah Franklin Bache (daughter of Benjamin Franklin). In 1780, in the midst of the war, the colonies raised over $340,000 through these female-run organizations.

Women in the Army

A handful of women felt so strongly about the revolutionary cause that they hid their gender and enlisted in the Continental Army. These women included Hannah Snell, Sally St. Claire, and Deborah Sampson, who was discovered after 17 months of service and honorably discharged. Some years later, Sampson was awarded a veteran’s pension for her service. Other women involved themselves in military activities by concealing and delivering dispatches and letters through enemy territory for the Continental Army. Notable patriots who served in this manner include Deborah Champion, Sara Decker Haligowski, Harriet Prudence Patterson Hall, and Lydia Darraugh. Regardless of how they served, women who fought or otherwise involved themselves in military activities were met with a range of responses, from admiration, to ambivalence, to contempt.

Loyalist Women

Many Loyalist women actually left the country during the Revolutionary War rather than stay to live among those they viewed as their enemies. For some women, this was a personal choice and done in defiance of their husbands or other male family members. For others who remained loyal to their husbands or families and their political allegiances, there was a constant risk of falling victim to mobs or vigilante groups that deemed them guilty of treason by association. Of those women who left their communities, many did so without any of their personal or family possessions.

Others actively contributed to the Loyalist cause by engaging in acts of resistance. Many were vocal about their refusal to swear loyalty to the new colonial government and encouraged others to resist as well. Some of these women also aided Loyalist soldiers or hid their male family members from authorities seeking traitors. Others hid important papers, supplies, and even money from the authorities.

American Indian Women

The revolutionary period was an intensely disruptive one for indigenous women. In many indigenous societies in North America, women were responsible for farming and trading, making wartime destruction particularly devastating for them and their ways of life. Following the Revolutionary War, the American government took an active role in prescribing new roles for American Indian men and women, encouraging women to work in textiles and forcing men to engage in agricultural tasks and trade. The disruption of gender roles caused severe problems within American Indian communities and marked a major break with their previous cultural mores.