Early Irish Immigrants

Protestant Irish immigrants from Ulster had been coming to British North America since the 1700s, and many had settled in the upland areas of the American interior. They participated in the American Revolution in large numbers and were a well-established community by the 1840s, when a second wave of Irish immigration began. At that time, descendants of the first wave of Irish immigration began to refer to themselves as "Scotch-Irish" to distinguish themselves from the newly arrived immigrants.

The Potato Famine

The Irish potato famine (1845–1849) destroyed much of the potato crop in Ireland and sent the entire country into starvation. Many emigrated to America in order to escape poverty and death. These new Irish immigrants were primarily Catholic, and most became unskilled workers who settled in urban areas in the Northeast and Midwest such as Boston, New York, and Chicago. Many Irish went to the emerging textile-mill towns of the Northeast; some also migrated to the interior of America to work on large-scale infrastructure projects such as canals and railroads.

Emigrants leaving Ireland

Irish immigration begin in the mid-eighteenth century and intensified during the great potato famine of 1845–1849.

By 1840, emigration had become a massive, relentless, and efficiently managed national enterprise. Including those who moved to Britain, between 9 and 10 million Irish people emigrated after 1700. The total flow was more than the population at its historical peak in the 1830s of 8.5 million. From 1830 to 1914, almost 5 million Irish traveled to the United States alone. In 1890, two of every five Irish-born people were living abroad. By the 2000s, an estimated 80 million people worldwide claimed some Irish descent; among them are 50 million Americans who claim "Irish" as their primary ethnicity.

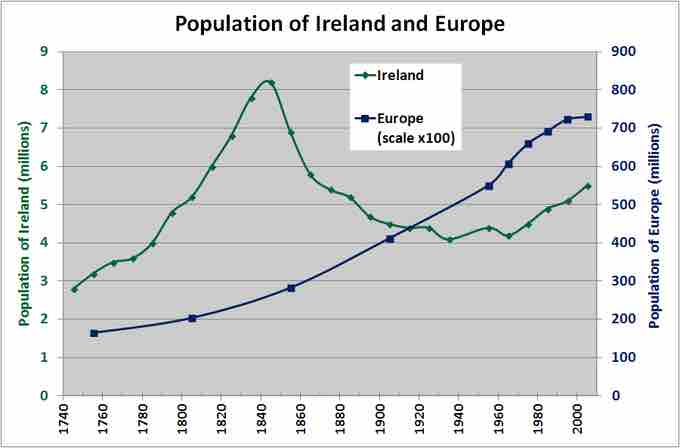

Graph of total population of Ireland

This graph shows the sharp decline in population in Ireland beginning in 1840. By 1855, almost 2 million Irish had emigrated.

Discrimination and Assimilation

As Irish immigrants poured into the United States in the decades preceding the Civil War, native-born laborers found themselves competing for jobs with new arrivals who were more likely to work longer hours for less pay. In Lowell, Massachusetts, for example, the daughters of New England farmers encountered competition from the daughters of Irish farmers suffering the effects of the potato famine; these immigrant women were more easily exploited by employers, working for far less money and enduring worse conditions than native-born women. Male Irish immigrants also competed with native-born men. The Irish provided a ready source of unskilled labor needed to lay railroad tracks and dig canals. American men with families to support grudgingly accepted low wages in order to keep their jobs.

As work became increasingly deskilled, no worker was irreplaceable, and no one’s job was safe. The resulting job competition caused a general hostility toward Irish immigrants. Nineteenth-century Protestant American "nativist" discrimination against Irish Catholics reached a peak in the mid-1850s, when the Know-Nothing Party tried to oust Catholics from public office. Much of the opposition came from Irish Protestants, as in the 1831 riots in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. During the 1830s, riots for control of job sites broke out in rural areas between Irish and local American work teams competing for construction jobs. After 1860, many Irish sang songs about "NINA signs" reading, "Help wanted—no Irish need apply."

Effects on American Culture

The Irish had a huge impact on America as a whole. Even today, many major cities in the United States retain a substantial Irish American community. Massachusetts mill towns such as Lawrence, Lowell, and Pawtucket attracted many Irish women in particular. The anthracite-coal region of northeastern Pennsylvania saw a massive influx of Irish during this time period; conditions in the mines eventually gave rise to groups and secret societies such as the Molly Maguires. As they assimilated, Irish Americans contributed to U.S. culture in a wide variety of fields, such as the fine and performing arts, film, literature, politics, sports, and religion.