Immigration in the Nineteenth Century

There was relatively little immigration into the United States from 1770 to 1830. Large-scale immigration resumed in the 1830s from Britain, Ireland, Germany, and other parts of western Europe, and the pace of immigration accelerated in the 1840s and 1850s. Most immigrants were attracted by the cheap farmland available in the United States; some immigrants were artisans and skilled factory workers attracted by the first stage of industrialization. Poor economic conditions in Europe drove many people to seek land, freedom, opportunity, and jobs in the new nation of America.

Immigration from Europe

Many new members of the working class came from the ranks of these immigrants, who brought new foods, customs, and religions. The Roman Catholic population of the United States, fairly small before this period, began to swell with the arrival of the Irish and the Germans. Many people immigrated from Ireland to work on infrastructure projects such as canals and railroads and settled in urban areas. Many Irish went to the emerging textile mill towns of the Northeast, while others became longshoremen in the growing Atlantic and Gulf port cities. About half of the immigrants from Germany headed to farms, especially in the Midwest and Texas, while the other half became craftsmen in urban areas.

Between 1841 and 1850, immigration nearly tripled, totaling 1,713,000 immigrants. The great potato famine in Ireland (1845–1849) drove the Irish to the United States in large numbers; they emigrated directly from their homeland to escape poverty and death. The failed Irish revolutions of 1848 brought many intellectuals and activists to exile in the United States.

The California Gold Rush

By 1848, thousands of California’s residents had gone north to the gold fields with visions of wealth, and in 1849, thousands of people from around the world followed them, marking the beginning of the gold rush. The California gold rush rapidly expanded the population of the new territory, attracting thousands of immigrants from Latin America, China, Australia, and Europe; it also prompted concerns about immigration, especially from China.

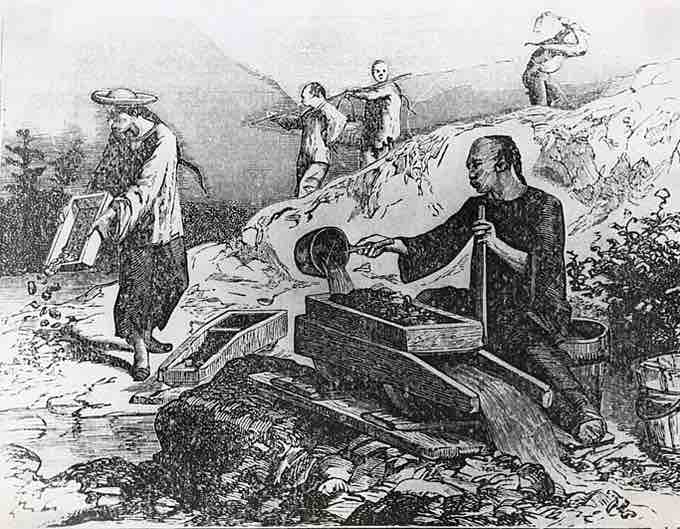

Foreigners were generally disliked, especially those from South America. The most discriminated against, however, were the thousands of Chinese immigrants. Eager to earn money to send to their families in Hong Kong and southern China, they quickly earned a reputation as frugal and hard workers who routinely took over diggings others had abandoned as worthless and worked them until every scrap of gold had been found. Many American miners, often spendthrifts, resented their presence and discriminated against them, believing the Chinese, who represented about 8 percent of the nearly 300,000 who arrived, were depriving them of the opportunity to make a living.

In 1850, California imposed a tax on foreign miners, and in 1858, it prohibited all immigration from China. Those Chinese who remained in the face of the growing hostility were often beaten and killed, and some Westerners made a sport of cutting off Chinese men’s queues, the long braids of hair worn down their backs. In 1882, Congress took up the power to restrict immigration by banning the further immigration of Chinese.

Chinese gold miners in California

One impetus for immigration was the gold rush of 1849, which brought to California thousands of immigrants from Latin America, China, Australia, and Europe.

Immigration and Worker Exploitation

As German and Irish immigrants poured into the United States in the decades preceding the Civil War, native-born laborers found themselves competing for jobs with new arrivals who were more likely to work longer hours for less pay. As a result, many wage workers in the North were largely hostile to immigration. In Lowell, Massachusetts, for example, the daughters of New England farmers encountered competition from the daughters of Irish farmers suffering the effects of the potato famine; these immigrant women were more likely to be exploited by employers, working for far less money and enduring worse conditions than native-born women. Male German and Irish immigrants also competed with native-born men. Germans, many of whom were skilled workers, took jobs in furniture making. The Irish provided a ready source of unskilled labor needed to lay railroad tracks and dig canals. American men with families to support grudgingly accepted low wages in order to keep their jobs. As work became increasingly deskilled, no worker was irreplaceable, and no one’s job was safe.