From 1863 until his death, President Abraham Lincoln took a moderate position on Reconstruction of the South and proposed plans to bring the South back into the Union as quickly and easily as possible. During this time, the Radical Republicans used Congress to block Lincoln's moderate approach. They sought to impose harsh terms on the South, thinking Lincoln's approach too lenient, as well as to upgrade the rights of freedmen (former slaves). The moderate position, held both by Lincoln and Vice President Andrew Johnson (who took over the presidency after Lincoln's death), prevailed until the election of 1866, at which point the Radicals were able to take control of policy, remove former Confederates from power, and enfranchise the freedmen. A Republican coalition came to power in nearly all of the Southern states and set out to transform the society by setting up a free-labor economy, with support from the army and the Freedmen's Bureau.

Lincoln's Plan for Reconstruction

During the American Civil War in December 1863, Abraham Lincoln offered a model for reinstatement of Southern states called the "10 Percent Plan." It decreed that a state could be reintegrated into the Union when 10 percent of the 1860 vote count from that state had taken an oath of allegiance to the United States and pledged to abide by emancipation. Voters then could elect delegates to draft revised state constitutions and establish new state governments. All Southerners, except for high-ranking Confederate Army officers and government officials, would be granted a full pardon. Lincoln guaranteed Southerners that he would protect their private property, though not their slaves. By 1864, Louisiana, Tennessee, and Arkansas had established fully functioning Unionist governments.

This policy was meant to shorten the war by offering a moderate peace plan. It was also intended to further Lincoln's emancipation policy by insisting that the new governments abolish slavery. Lincoln's reconstructive policy toward the South was lenient because he wanted to popularize his Emancipation Proclamation. Lincoln feared that compelling enforcement of the proclamation could lead to the defeat of the Republican Party in the election of 1864, and that popular Democrats could overturn his proclamation. Lincoln's plan successfully began the Reconstruction process of ratifying the Thirteenth Amendment in all states.

Congress Responds

Congress reacted sharply to this proclamation of Lincoln's plan. Most moderate Republicans in Congress supported the president's proposal for Reconstruction because they wanted to bring a swift end to the war, but other Republicans feared that the planter aristocracy would be restored and the blacks would be forced back into slavery.

The Radical Republicans opposed Lincoln's plan because they thought it too lenient toward the South. Radical Republicans believed that Lincoln's plan for Reconstruction was not harsh enough because, from their point of view, the South was guilty of starting the war and deserved to be punished as such. Radical Republicans hoped to control the Reconstruction process, transform Southern society, disband the planter aristocracy, redistribute land, develop industry, and guarantee civil liberties for former slaves.

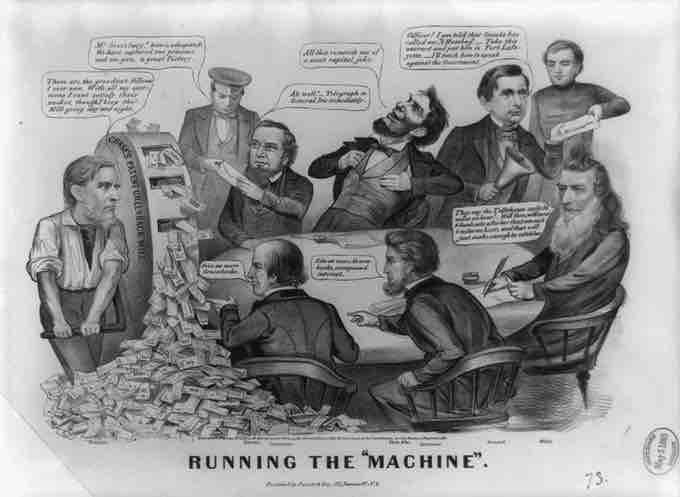

"Running the 'Machine.'"

An 1864 political cartoon—featuring William Fessenden, Edwin Stanton, William Seward, Gideon Welles, Lincoln, and others—takes a swing at Lincoln's administration.

Although the Radical Republicans were the minority party in Congress, they managed to sway many moderates in the postwar years and came to dominate Congress in later sessions. In the summer of 1864, the Radical Republicans passed a new bill to counter the plan, known as the "Wade-Davis Bill." As opposed to Lincoln's plan, this new bill would make readmission into the Union more difficult. The bill stated that for a state to be readmitted, the majority of the state would have to take a loyalty oath, not just ten percent. Lincoln later pocket vetoed this new bill.

Freedmen's Bureau

In March 1865, Congress created a new agency, the Freedmen's Bureau. This agency provided food, shelter, medical aid, employment aid, education, and other needs for blacks and poor whites. It also attempted to oversee new relations between freedmen and their former masters in a free-labor market. The Freedmen's Bureau was the largest federal aid relief plan at the time, and it was the first large scale governmental welfare program.

With the help of the bureau, the recently freed slaves began voting, forming political parties, and assuming the control of labor in many areas. The Freedmen's Bureau helped to start a change of power in the South that drew national attention from the Republicans in the North to the conservative Democrats in the South.

Congress's Reconstruction Bills

Andrew Johnson, Lincoln's vice president who took over the presidency after Lincoln's assassination, attempted to continue Lincoln's vision for Reconstruction. However, Congress continued to pass more radical legislation. The Radical Republican vision for Reconstruction, also called "Radical Reconstruction," was further bolstered in the 1866 election, when more Republicans took office in Congress. During this era, Congress passed three important Reconstruction amendments.

The Thirteenth Amendment abolishing slavery was ratified in 1865. The Fourteenth Amendment, proposed in 1866 and ratified in 1868, guaranteed U.S. citizenship to all persons born or naturalized in the United States and granted them federal civil rights. The Fifteenth Amendment, proposed in late February 1869 and passed in early February 1870, decreed that the right to vote could not be denied because of "race, color, or previous condition of servitude."

Congress also passed the Reconstruction Acts. These initially were vetoed by President Johnson, but later were overridden by Congress. The first Reconstruction Act placed 10 Confederate states under military control, grouping them into five military districts that would serve as the acting government for the region. One major purpose was to recognize and protect the right of African Americans to vote. Under a system of martial law in the South, the military closely supervised local government, elections, and the administration of justice, and tried to protect office holders and freedmen from violence. Blacks were enrolled as voters and former Confederate leaders were excluded for a limited period.

The Reconstruction Acts denied the right to vote for men who had sworn to uphold the Constitution and then rebelled against the federal government. As a result, in some states the black population was a minority, while the number of blacks who were registered to vote nearly matched the number of white registered voters. In addition, Congress required that each state draft a new state constitution—which would have to be approved by Congress—and that each state ratify the Fourteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution and grant voting rights to black men.

Conclusion

Lincoln is typically portrayed as taking the moderate position and fighting the Radical positions. There is considerable debate about how well Lincoln, had he lived, would have handled Congress during the Reconstruction process that took place after the Civil War ended. One historical camp argues that Lincoln's flexibility, pragmatism, and superior political skills with Congress would have solved Reconstruction with far less difficulty. The other camp believes that the Radicals would have attempted to impeach Lincoln, just as they did his successor, Andrew Johnson, in 1868.