WARREN COURT

The Warren Court refers to the Supreme Court of the United States between 1953 and 1969, when Earl Warren served as Chief Justice. Warren led a liberal majority that used judicial power in dramatic fashion, to the consternation of conservative opponents. The Warren Court expanded civil rights, civil liberties, judicial power, and federal power .

The court was both applauded and criticized for bringing an end to racial segregation in the United States, incorporating the Bill of Rights (i.e. applying it to states), and ending officially sanctioned voluntary prayer in public schools. The period is recognized as a high point in judicial power that has receded ever since, but with a substantial continuing impact. Prominent members of the Court during the Warren era besides the Chief Justice included Justices William J. Brennan, Jr., William O. Douglas, Hugo Black, Felix Frankfurter, and John Marshall Harlan II.

Warren took his seat January 11, 1954, on a recess appointment by President Eisenhower. The Senate confirmed him six weeks later. When Warren joined the Court, all the justices had been appointed by Franklin D. Roosevelt or Truman, and all were committed New Deal liberals. However, they disagreed about the role that the courts should play in achieving liberal goals. The Court was split between two warring factions. Felix Frankfurter and Robert H. Jackson led one faction, which insisted upon judicial self-restraint and insisted courts should defer to the policy making prerogatives of the White House and Congress. Hugo Black and William O. Douglas led the opposing faction that agreed the court should defer to Congress in matters of economic policy, but felt the judicial agenda had been transformed from questions of property rights to those of individual liberties, and in this area courts should play a more central role. Warren's belief that the judiciary must seek to do justice, placed him with the latter group, although he did not have a solid majority until after Frankfurter's retirement in 1962. When Frankfurter retired, President John F. Kennedy named labor lawyer Arthur Goldberg to replace him and Warren finally had the fifth liberal vote for his majority.

1953 Supreme Court

The Supreme Court in 1953, with Chief Justice Earl Warren sitting center. Warren made the Supreme Court a power center on a more even basis with Congress and the Presidency, especially through four landmark decisions: Brown v. Board of Education (1954), Gideon v. Wainwright (1963), Reynolds v. Sims (1964), and Miranda v. Arizona (1966).

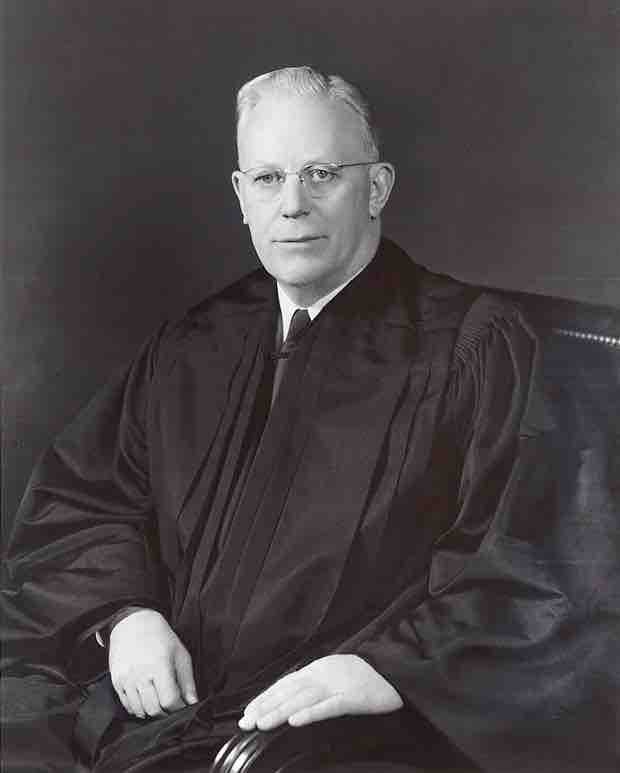

CHIEF JUSTICE EARL WARREN

Warren boasted a strong political background, having served three terms as Governor of California, and was the Republican candidate for vice president in 1948. He brought a strong belief in the remedial power of law. Warren's and his view of the law was pragmatic, seeing it as an instrument for obtaining equity and fairness. He also focused on broad ethical principles, rather than narrower interpretative structures or strict precedent. Warren often used this worldview in deciding groundbreaking cases such as Brown v. Board of Education, Reynolds v. Sims and Miranda v. Arizona, where such traditional sources of precedent were stacked against him.

Chief Justice Earl Warren

Warren is best known for the liberal decisions of the so-called Warren Court, which outlawed segregation in public schools and transformed many areas of American law, especially regarding the rights of the accused, ending public school-sponsored prayers, and requiring "one man–one vote" rules of apportionment of election districts.

LEADERSHIP

Warren's court was characterized by remarkable consensus, particularly in some of the most controversial cases. Brown v. Board of Education, Gideon v. Wainwright, and Cooper v. Aaron were unanimously decided. In an unusual action, the decision in Cooper (which held that the states are bound by the Court's decisions and must enforce them even if the states disagreed with them) was personally signed by all nine justices, with the three new members of the Court adding that they supported and would have joined the Court's decision in Brown v. Board. Warren's greatest asset—what made him in the eyes of many of his admirers "Super Chief"—was his political skill in manipulating the other justices. Over the years his ability to lead the Court, to forge majorities in support of major decisions, and to inspire liberal forces around the nation, outweighed his intellectual weaknesses.

The Warren Court's doctrine may be seen as proceeding aggressively in three general areas: its decisive reading of the first eight amendments in the Bill of Rights, its commitment to unblocking the channels of political change ("one-man, one-vote"), and its vigorous protection of the rights of racial minority groups.

The Warren Court's decisions were also strongly federal in thrust, as the Court read Congress's power quite broadly and often expressed an unwillingness to allow constitutional rights to vary from state to state.

HISTORICALLY SIGNIFICANT DECISIONS

The Warren Court reached many decisions that changed not only the laws of the United States but contributed to significant social changes. Some of its most important cases were:

- Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka (1954) declared state laws establishing separate public schools for black and white students to be unconstitutional. The decision overturned the Plessy v. Ferguson decision of 1896, which allowed state-sponsored segregation, insofar as it applied to public education. Handed down on May 17, 1954, the Warren Court's unanimous (9–0) decision stated that "separate educational facilities are inherently unequal." As a result, de jure racial segregation was ruled a violation of the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment of the United States Constitution. This ruling paved the way for integration and was a major victory of the Civil Rights Movement. However, the decision's fourteen pages did not spell out any sort of method for ending racial segregation in schools, and the Court's second decision in Brown II only ordered states to desegregate "with all deliberate speed."

- Gideon v. Wainwright (1963) unanimously ruled that states are required under the Fourteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution to provide counsel in criminal cases to represent defendants who are unable to afford to pay their own attorneys. The case extended the right to counsel, which had been found under the Fifth and Sixth Amendments to impose requirements on the federal government, by ruling that this right imposed those requirements upon the states as well.

- Miranda v. Arizona (1966) held (in a 5–4 majority) that both inculpatory and exculpatory statements made in response to interrogation by a defendant in police custody will be admissible at trial only if the prosecution can show that the defendant was informed of the right to consult with an attorney before and during questioning and of the right against self-incrimination before police questioning, and that the defendant not only understood these rights, but voluntarily waived them. This had a significant impact on law enforcement in the United States, by making what became known as the Miranda rights part of routine police procedure to ensure that suspects were informed of their rights.

- Loving v. Virginia (1967) invalidated laws prohibiting interracial marriage.The case was brought by Mildred Loving, a black woman, and Richard Loving, a white man, who had been sentenced to a year in prison in Virginia for marrying each other. Their marriage violated the state's anti-miscegenation statute, the Racial Integrity Act of 1924, which prohibited marriage between people classified as "white" and people classified as "colored." The Supreme Court's unanimous decision determined that this prohibition was unconstitutional, overruling Pace v. Alabama (1883) and ending all race-based legal restrictions on marriage in the United States.

- The one man, one vote cases (Baker v. Carr and Reynolds v. Sims) of 1962–1964, had the effect of ending the over-representation of rural areas in state legislatures, as well as the under-representation of suburbs. Central cities--which had long been underepresented--were now losing population to the suburbs and were not greatly affected. Warren's priority on fairness shaped other major decisions. In 1962, over the strong objections of Frankfurter, the Court agreed that questions regarding malapportionment in state legislatures were not political issues, and thus were not outside the Court's purview. For years underpopulated rural areas had deprived metropolitan centers of equal representation in state legislatures. In Warren's California, Los Angeles County had only one state senator. Cities had long since passed their peak, and now it was the middle class suburbs that were underrepresented. Frankfurter insisted that the Court should avoid this "political thicket" and warned that the Court would never be able to find a clear formula to guide lower courts in the rash of lawsuits sure to follow. But Douglas found such a formula: "one man, one vote." Unlike the desegregation cases, in this instance, the Court ordered immediate action.

In other cases, the Court also ruled that the Constitution protects a general right to privacy (Griswold v. Connecticut) and it established that public schools cannot have official prayer (Engel v. Vitale) or mandatory Bible readings (Abington School District v. Schempp). The Warren Court was credited with reading an equal protection clause into the Fifth Amendment (Bolling v. Sharpe).

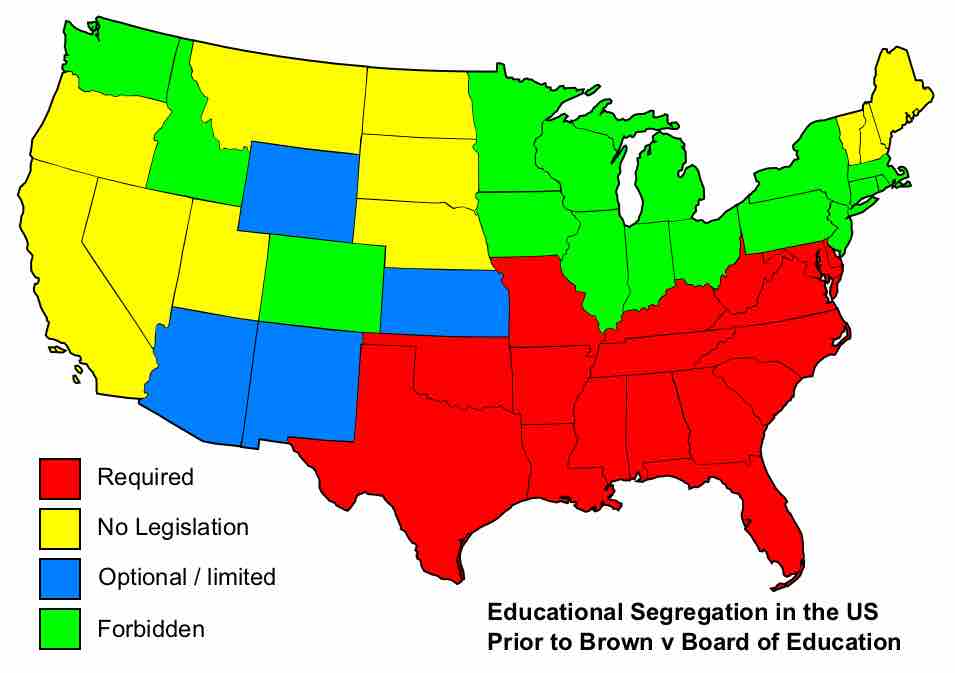

Brown vs. Board of Education

Educational segregation in the US prior to Brown vs. Board of Education