RACISM IN THE MILITARY

African Americans first started enlisting in the military on June 1, 1942. Over two and a half million African American men registered in the military draft and African American women volunteered their services in the war. During the war, African-American enlistment was at an all time high, with more than 1 million serving in the armed forces. However, the U.S. military was still heavily segregated. The air force and the marines had no African Americans enlisted in their ranks, and the navy only accepted black Americans as cooks and waiters. The army had only five African-American officers. In addition, no African-American would receive the Medal of Honor during the war and their tasks in the war were largely reserved to noncombat units.

Despite their high enlistment rate in the U.S. Army, most African American soldiers still served only as truck drivers and as stevedores (except for some separate tank battalions and Army Air Forces escort fighters). In the midst of the Battle of the Bulge in December 1944, a major German offensive campaign launched on Western Front (in the region of Wallonia in Belgium, France, and Luxembourg), General Eisenhower was severely short of replacement troops for existing military units which were totally white in composition. Consequently, he made the decision to allow African American soldiers to pick up a weapon and join the white military units to fight in combat for the first time. More than 2,000 black soldiers had volunteered to go to the front.

At the start of the Battle of the Bulge, the 333rd Battalion, a combat unit composed entirely of African American soldiers led by white officers, was attached to the 106th Infantry Division. Prior to the German offensive, the 106th division was tasked with holding a 26-mile (41.8 kilometers) long length of the front. The 333rd was badly affected, losing nearly 50% of its soldiers, including its commanding officer. Eleven of its soldiers were cut off from the rest of the unit and attempted to escape German capture, but were massacred on sight by the Waffen SS. The remnants of the battalion retreated to Bastogne where they linked up the 101st. The vestiges of the 333rd were attached to its sister unit the 969th Battalion. By December, the Germans had surrounded Bastogne, which was defended by the 101st Airborne Division, the all African American 969th Artillery Battalion, and Combat Command B of the 10th Armored Division. Despite low supplies of food and ammunition, and being limited to only 10 artillery rounds per day, the 333rd fought tenaciously, successfully holding their sector of the front despite repeated German assaults.

TUSKEGEE AIRMEN

The Tuskegee Airmen were the first African-American military aviators in the United States Armed Forces. Officially, they formed the 332nd Fighter Group and the 477th Bombardment Group of the United States Army Air Forces. The Tuskegee Airmen were subjected to discrimination, both within and outside the army. All black military pilots who trained in the United States trained at Moton Field, the Tuskegee Army Air Field, and were educated at Tuskegee University, located near Tuskegee, Alabama. The name also applies to the navigators, bombardiers, mechanics, instructors, crew chiefs, nurses, cooks and other support personnel for the pilots.

Although the 477th Bombardment Group trained with North American B-25 Mitchell bombers, they never served in combat. The 99th Pursuit Squadron (later, 99th Fighter Squadron) was the first black flying squadron, and the first to deploy overseas (to North Africa in April 1943, and later to Sicily and Italy). The 332nd Fighter Group was the first black flying group. The group deployed to Italy in early 1944. In June 1944, the 332nd Fighter Group began flying heavy bomber escort missions, and in July 1944, the 99th Fighter Squadron was assigned to the 332nd Fighter Group, which then had four fighter squadrons.

Benjamin O. Davis, Jr. served as commander of the famed Tuskegee Airmen during the War. He later went on to become the first African American general in the United States Air Force. His father, Benjamin O. Davis, Sr., had been the first African American Brigadier General in the Army (1940).

THE GOLDEN THIRTEEN

In June 1941, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed the executive order (8802) that prohibited racial discrimination in the national defense industry. Responding to pressure from First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt and Assistant Secretary of the Navy Adlai Stevenson, in January 1944, the Navy began an accelerated 2-month officer training course for 16 African-American enlisted men at Camp Robert Smalls, Recruit Training Center Great Lakes (now known as Great Lakes Naval Training Station), in Illinois. The class average at graduation was 3.89. Although all sixteen members of the class passed the course, only twelve were commissioned in March 1944. Because Navy policy prevented them from being assigned to combatant ships, early black officers wound up being detailed to run labor gangs ashore.

PORT CHICAGO DISASTER

The Port Chicago disaster was a deadly munitions explosion that occurred on July 17, 1944, at the Port Chicago Naval Magazine in Port Chicago, California. Munitions detonated while being loaded onto a cargo vessel bound for the Pacific Theater of Operations, killing 320 sailors and civilians and injuring 390 others. Most of the dead and injured were enlisted African-American sailors.

A month later, unsafe conditions inspired hundreds of servicemen to refuse to load munitions, an act known as the Port Chicago Mutiny. Fifty men—called the "Port Chicago 50"—were convicted of mutiny and sentenced to long prison terms. Forty-seven of the 50 were released in January 1946; the remaining three served additional months in prison.

During and after the trial, questions were raised about the fairness and legality of the court-martial proceedings. Due to public pressure, the United States Navy reconvened the courts-martial board in 1945; the court affirmed the guilt of the convicted men. Widespread publicity surrounding the case turned it into a cause célèbre among certain Americans; it and other race-related Navy protests of 1944–45 led the Navy to change its practices and initiate the desegregation of its forces beginning in February 1946.

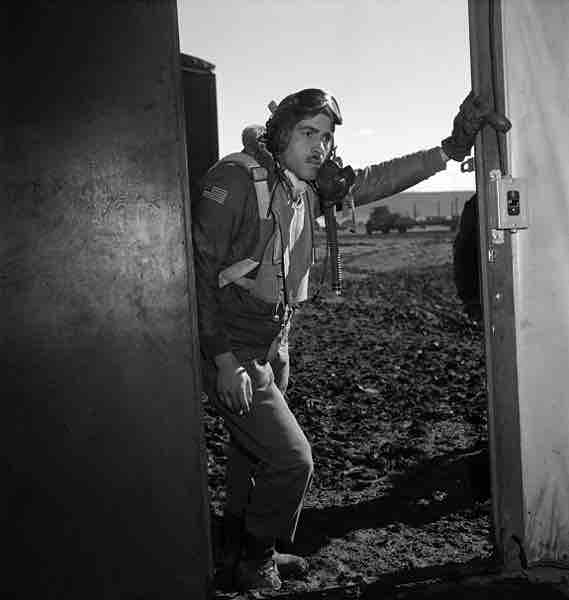

Tuskegee Airmen

The Tuskegee Airmen were the first African-American pilots in United States military history; they flew with distinction during World War II. Portrait of Tuskegee airman Edward M. Thomas by photographer Toni Frissell, March 1945.

African-American soldiers served with distinction in World War II, despite racism and segregation

12th AD soldier with German prisoners of war, April 1945.

RECOGNITION

The desegregation of all U.S. Armed Forces did not take place until after World War II. In 1947, A. Philip Randolph, prominent civil rights leader, along with colleague Grant Reynolds, renewed efforts to end discrimination in the armed services, forming the Committee Against Jim Crow in Military Service and Training, later renamed the League for Non-Violent Civil Disobedience Against Military Segregation. Coseqnutely, Truman's Order expanded on Executive Order 8802 by establishing equality of treatment and opportunity in the military for people of all races, religions, or national origins. In July 1948, the Executive Order 9981 abolished racial discrimination in the armed forces and eventually led to the end of segregation in the services.

It was not until the 1990s that black World War II military men were awarded the Medal of Honor - the highest military decoration presented by the United States government to a member of its armed forces. A 1993 study commissioned by the United States Army investigated racial discrimination in the awarding of medals. At the time, no Medals of Honor had been awarded to black soldiers who served in World War II. After an exhaustive review of files, the study recommended that several black Distinguished Service Cross recipients be upgraded to the Medal of Honor. On January 13, 1997, President Bill Clinton awarded the Medal to seven African American World War II veterans; of these, only Vernon Baker was still alive. The posthumous recipients were Major Charles L. Thomas, First Lieutenant John R. Fox, Staff Sergeant Ruben Rivers, Staff Sergeant Edward A. Carter, Jr., Private First Class Willy F. James, Jr., Private George Watson.

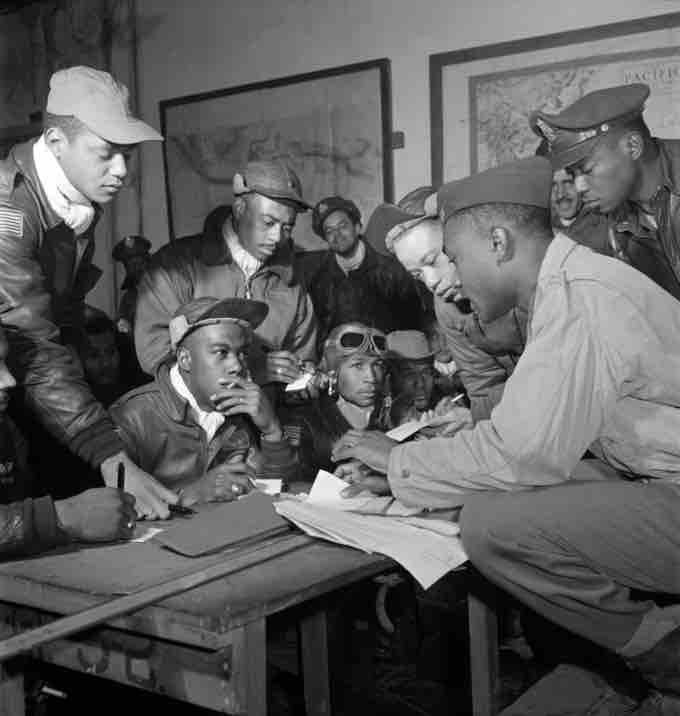

Tuskegee Airmen

Tuskegee airmen at Ramitelli, Italy, March 1945.