HISPANIC AMERICANS IN WORLD WAR II

When the United States officially entered World War II, Hispanic Americans were among the many American citizens who joined the ranks of United States Armed Forces as volunteers or through the draft. Hispanic Americans fought in every major battle of World War II, in which the armed forces of the United States were involved. According to the National World War II Museum, between 250,000 and 500,000 Hispanic Americans served in the U.S. Armed Forces during World War II, out of a total of 12,000,000, constituting 2.3% to 4.7% of the U.S. Armed Forces. The exact number is unknown as, at the time, Hispanics were not tabulated separately and were generally included in the white population census count.

EUROPEAN THEATER

In the European Theater, the majority of Hispanic Americans served in regular units. Some active combat units recruited from areas of high Hispanic population, such as the 65th Infantry Regiment from Puerto Rico and the 141st Regiment of the 36th Texas Infantry, were made up mostly of Hispanics.

Hispanics of the 141st Regiment of the 36th Infantry Division were some of the first American troops to land on Italian soil at Salerno. Company E of the 141st Regiment was entirely Hispanic. The 36th Infantry Division fought in Italy and France, enduring heavy casualties during the crossing of the Rapido River near Monte Cassino, Italy.

In 1943, the 65th Infantry was sent to North Africa, where they underwent further training. By April 29, 1944, the Regiment had landed in Italy and moved on to Corsica. On September 22, 1944, the 65th Infantry landed in France and was committed to action in the Maritime Alps at Peira Cava. On December 13, 1944, the 65th Infantry, under the command of Lieutenant Colonel Juan César Cordero Dávila, relieved the 2nd Battalion of the 442nd Infantry Regiment, a regiment which was made up of Japanese Americans under the command of Col. Virgil R. Miller, a native of Puerto Rico.

The 3rd Battalion fought against and defeated Germany's 34th Infantry Division's 107th Infantry Regiment. There were 47 battle casualties. On March 18, 1945, the regiment was sent to the District of Mannheim and assigned to military occupation duties after the end of the war. The regiment suffered 23 soldiers killed in action.

Sergeant First Class Agustín Ramos Calero, a member of the 65th Infantry who was reassigned to the 3rd U.S. Infantry Division because of his ability to speak and understand English, was one of the most decorated Hispanic soldiers in the European Theater.

PACIFIC THEATER

Two National Guard units: the 200th and the 515th Battalions, were activated in New Mexico in 1940. Made up mostly of Spanish-speaking Hispanics from New Mexico, Arizona and Texas, the two battalions were sent to Clark Field in the Philippine Islands. Shortly after the Imperial Japanese Navy launched its surprise attack on the American Naval Fleet at Pearl Harbor, Japanese forces attacked the American positions in the Philippines. General Douglas MacArthur moved his forces, which included the 200th and 515th, to the Bataan Peninsula, where they fought alongside Filipinos in a three-month stand against the invading forces.

By April 9, 1942, rations, medical supplies, and ammunition became scarce. Officers ordered the starving and outnumbered troops of the 200th and 515th Battalions to lay down their arms and surrender to the Japanese. These Hispanic and non-Hispanic soldiers endured the 12-day, 85-mile (137 km) Bataan Death March from Bataan to the Japanese prison camps, where they were force-marched in scorching heat through the Philippine jungle.

The 158th Regimental Combat Team, an Arizona National Guard unit of mostly Hispanic soldiers, also fought in the Pacific Theater. Early in the war, the 158th, nicknamed the "Bushmasters," had been deployed to protect the Panama Canal and had completed jungle training. The unit later fought the Japanese in the New Guinea area in heavy combat and was involved in the liberation of the Philippine Islands.

HISPANIC WOMEN IN THE MILITARY AND ON HOME FRONT

Prior to World War II, traditional Hispanic cultural values assumed women should be homemakers. Thus women rarely left the home to earn an income. As such, they were discouraged from joining the military. Only a small number of Hispanic women joined the military before World War II. However, with the outbreak of World War II, cultural norms began to change. With the creation of the Women's Army Auxiliary Corps (WAAC), predecessor of the Women's Army Corps (WAC), and the U.S. Navy Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service (WAVES), women could attend to certain administrative duties left open by the men who were reassigned to combat zones.

In 1944, the Army recruited women in Puerto Rico for the Women's Army Corps (WAC). Over 1,000 applications were received for the unit, which was to be composed of only 200 women. After their basic training at Fort Oglethorpe, Georgia, the Puerto Rican WAC unit, Company 6, 2nd Battalion, 21st Regiment of the Women's Army Auxiliary Corps, a segregated Hispanic unit, was assigned to the Port of Embarkation of New York City to work in military offices that planned the shipment of troops around the world.

However, not all of the WAAC units were stationed in the mainland USA. In January 1943, the 149th WAAC Post Headquarters Company became the first WAAC unit to go overseas when they went to North Africa. Serving overseas was dangerous for women; if captured, WAACs, as "auxiliaries" serving with the Army rather than in it, did not have the same protections under international law as male soldiers.

As Hispanic female nurses were initially not accepted into the Army Nurse Corps or Navy Nurse Corps, many Hispanic women went to work in the factories which produced military equipment. As more Hispanic men joined the armed forces, a need for bilingual nurses became apparent and the Army started to recruit Hispanic nurses. In 1944, the Army Nurse Corps (ANC) decided to accept Puerto Rican nurses. Thirteen women submitted applications, were interviewed, underwent physical examinations, and were accepted into the ANC. Eight of these nurses were assigned to the Army Post at San Juan, Puerto Rico, where they were valued for their bilingual abilities.

The broad changes in the role of women caused by a need for labor on the home front affected also the role of Hispanic women, who, additionally to serving as nurses, worked as secretaries, helped build airplanes, made ammunition in factories, and worked in shipyards.

DISCRIMINATION

In 1940, Hispanic Americans constituted around 1.5% of the population in the United States. While during World War II, the United States Army was segregated and Hispanics were often categorized as white, racism and xenophobia targeted at Hispanic Americans were common. Many Hispanics, including the Puerto Ricans who resided on the mainland, served alongside their "white" counterparts, while those who were categorized "black" served in units mostly made up of African-Americans. The majority of the Puerto Ricans from the island served in Puerto Rico's segregated units, like the 65th Infantry and the Puerto Rico National Guard's 285th and 296th regiments.

Discrimination against Hispanics has been documented in several first-person accounts by Hispanic soldiers who fought in World War II. After returning home, Hispanic soldiers experienced the same discrimination as before departure. According to one former Hispanic soldier, "There was the same discrimination in Grand Falls (Texas), if not worse" than when he had departed. While Hispanics could work for 2 per day, whites could get jobs working in petroleum fields that earned $18 per day. In his town, signs read "No Mexicans, whites only," and only one restaurant would serve Hispanics. The American GI Forum was started to ensure the rights of Hispanic World War II veterans.

Discrimination also extended to those killed during the war. In one notable case, the owner of a funeral parlor refused to allow the family of Private Felix Longoria, a soldier killed in action in the Philippines, to use his facility because "whites would not like it."

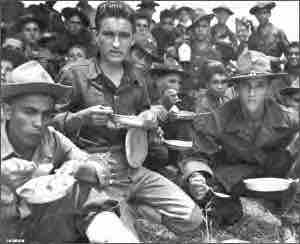

Puerto Rican Soldiers in World War II

Soldiers of the 65th Infantry training in Salinas, Puerto Rico, August 1941.