Introduction: The Panic of 1837

The Panic of 1837 was a financial crisis, or market correction, driven by speculative fever. Inflation became rampant after federal deposits to the Second Bank of the United States were withdrawn, based on the assumption that the government was selling land for state bank notes of questionable value. On May 10, 1837, every bank in New York City began to accept payment only in specie ("hard money," usually in the form of gold and silver coinage), forcing a dramatic, deflationary backlash. The Panic was followed by a five-year economic depression fraught with bank failures and unprecedented unemployment levels.

Causes

Economic Booms and Busts

Growth of the U.S. economy during the Market Revolution produced an upsurge in investment in emerging financial sectors. These speculative investments were frequently made with borrowed funds, resulting in large-scale cycles of boom and bust in the early 1800s.

The tremendous growth in the agricultural sector in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries encouraged land speculation, or the purchasing of land with the expectation that its value would continue to increase. Cotton, at first a small-scale crop in the South, boomed following Eli Whitney's invention of the cotton gin in 1793. Raw cotton from southern plantations was shipped to textile mills in Britain, France, and, by the 1820s, New England. Millions also migrated to fertile farmlands of the Midwest, and new roads and waterways opened up new markets for western farm products.

The U.S. government borrowed heavily to finance the War of 1812, which caused tremendous strain on the banks' reserves of specie (gold and silver), leading to a suspension of specie payments in 1814. The suspension of the obligation to back transactions with hard currency spurred the establishment of new banks and the expansion of bank-note issues. This inflation of money encouraged unsustainable investments.

Jackson's Policies

The Panic of 1837 was influenced by the economic policies of President Jackson. During his term, Jackson created the Specie Circular by executive order and refused to renew the charter of Second Bank of the United States, leading government funds to be withdrawn from the bank. Jackson was motivated by the concern that the government was selling land for state bank notes of questionable value and that the bank was issuing excessive paper money unbacked by specie reserves.

Martin Van Buren became president in March of 1837, five weeks before the Panic began; he was later blamed for the Panic. Some people argued that Van Buren's refusal to involve the government in the economy contributed to the Panic's duration and severity. However, Jacksonian Democrats argued that the Bank had funded rampant speculation and introduced paper-money inflation, and was therefore chiefly responsible for the crisis. The financial crisis of 1837 doomed Van Buren's reelection in 1840.

Effects and Aftermath

Virtually the whole nation felt the effects of the Panic. Connecticut, New Jersey, and Delaware experienced the most stress in their mercantile districts. In 1837, Vermont's business and credit systems took a hard blow. Vermont had a period of alleviation in 1838 but was hit hard again in 1839 and 1840. New Hampshire was not as affected by the Panic as its neighbors; it had no permanent debt as of 1838 and did not experience significant economic stress during the following years.

Within two months, the losses from the bank failures in New York alone totaled nearly 100 million dollars. Of 850 total banks in the United States, 343 were closed and another 62 partially failed. The entire state bank system had received a colossal shock, which continued to reverberate throughout the country in the ensuing years. In particular, the publishing industry suffered greatly due to the ensuing depression.

Conditions in the South were much worse than the conditions in the Northeast. In Virginia, North Carolina, and South Carolina, the Panic led to increased interest in diversifying crops. New Orleans experienced a general depression in business, and the conditions of its financial market remained negative throughout 1843. Many planters in Mississippi had spent much of their money in advance, leading to their complete bankruptcy. By 1839, many of the plantations were unable to continue cultivation. Florida and Georgia did not feel the effects as early as Louisiana, Alabama, or Mississippi; however, they began to feel the negative effects of the Panic in the 1840s.

The West did not initially feel as much pressure as the North or the South. Ohio, Indiana, and Illinois were agricultural states, and the good crops of 1837 were a relief to farmers. By 1839, however, agricultural prices had fallen and agriculturists felt the pressure.

Recovery

In 1842, the American economy was able to rebound somewhat and overcome the five-year depression, due in part to the Tariff of 1842. However, according to most accounts, the economy did not fully rebound until 1843. Most economists also agree that there was a brief recovery from 1838 to 1839; that recovery ended as the Bank of England and Dutch creditors raised interest rates.

Employment status and satisfaction

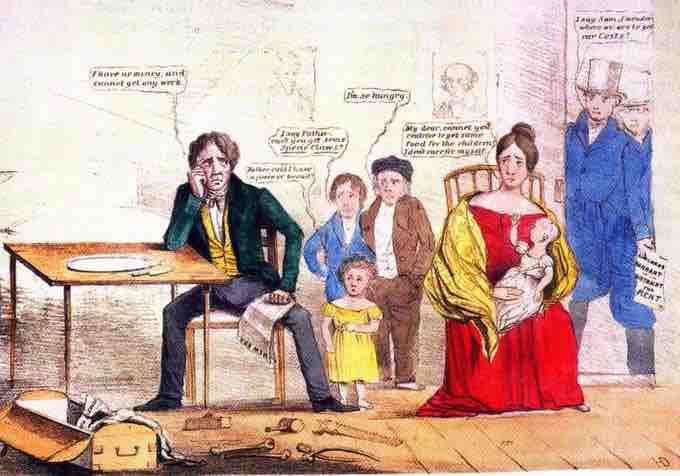

Whig cartoons depicted the economic challenges caused by the Panic of 1837. In this cartoon, an unemployed man, unable to provide food for his family, greets a rent collector at his front door. A faint portrait of President Van Buren hangs on the wall.