New Netherland

New Netherland was the territory on the eastern coast of North America established by Henry Hudson in 1609. It encompassed parts of the later states of New Jersey, Delaware, Connecticut, Pennsylvania, and Rhode Island. In 1609, Henry Hudson, an English explorer, was hired by the Flemish Protestants running the Dutch East India Company in Amsterdam to find a northeast passage to Asia. Turned back by the ice of the Arctic, Hudson sailed up the major river that would later bear his name.

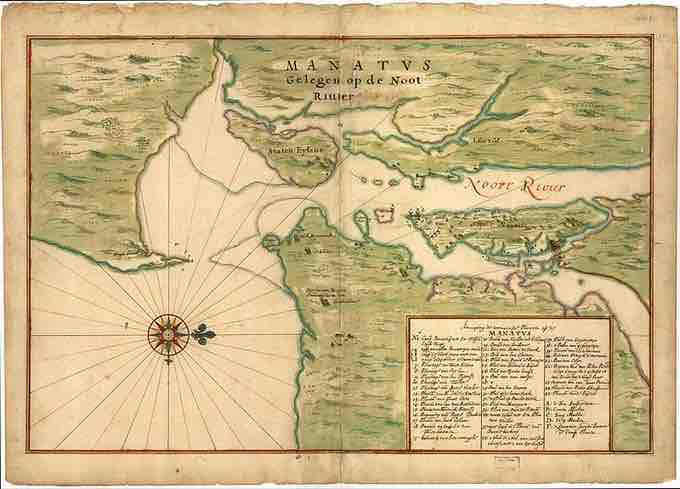

Joan Vinckeboons (Johannes Vingboon), "Manatvs gelegen op de Noot Riuier", 1639

In this map (c. 1639), Manhattan is situated on the North River.

Chartered in 1614, New Amsterdam was a colonial province of the Republic of the Seven United Netherlands. For the capital they chose the island of Manhattan, located at the mouth of the river explored by Hudson, which at that time was called the North River. New Netherland became a province of the Dutch Republic in 1624. For two centuries, New Netherland Dutch culture characterized the region, and their concepts of civil liberties and pluralism introduced in the province became mainstays of American political and social life.

The Iroquois and Algonquians

Seeking to enter the fur trade, the Dutch cultivated close relations with the Five Nations of the Iroquois. The Algonquian Lenape people along the Lower Hudson were seasonally migrational. Collectively called River Indians by the Dutch, they were also known as the Wecquaesgeek, Hackensack, Raritan, Canarsee, and the Tappan. The Munsee inhabited the Hudson Valley highlands and northern New Jersey, while Minquas (called the Susquehannocks by the English) lived west of the Zuyd River along and beyond the Susquehanna River, which the Dutch regarded as their boundary with Virginia.

The Dutch, through their trade of manufactured goods with the Iroquois and Algonquians, presumed they had exclusive rights to farming, hunting, and fishing in the region. The American Indians, while willing to share the land with the Europeans, did not expect or intend to leave or give up access, however. Increasing encroachment by European settlers led to the early stages of violent conflict. Over the next few decades, wars with the American Indians erupted, as well as conflicts with the English.

Transfer to the English

Charles II of England set his sights on the Dutch colony of New Netherland. The English takeover of New Netherland originated in the imperial rivalry between the Dutch and the English. During the Anglo-Dutch wars of the 1650s and 1660s, the two powers attempted to gain commercial advantages in the Atlantic World. During the Second Anglo-Dutch War (1664–1667), English forces gained control of the Dutch fur trading colony of New Netherland, and in 1664, Charles II gave this colony (including present-day New Jersey) to his brother James, Duke of York (later James II). The colony and city were renamed New York in his honor. The Dutch in New York chafed under English rule. In 1673, during the Third Anglo-Dutch War (1672–1674), the Dutch recaptured the colony; however, at the end of the conflict, the English had regained control.

The Duke of York never visited his colony, named New York in his honor, and exercised little direct control over it. He decided to administer his government through governors, councils, and other officers appointed by him. It wasn’t until 1683, almost 20 years after the English took control of the colony, that colonists were able to convene a local representative legislature. The assembly’s 1683 Charter of Liberties and Privileges set out the traditional rights of Englishmen, like the right to trial by jury and the right to representative government.

The English continued the Dutch patroonship system, granting large estates to a favored few families. The largest of these estates, at 160,000 acres, was given to Robert Livingston in 1686. The Livingstons and the other manorial families who controlled the Hudson River Valley formed a formidable political and economic force. Eighteenth-century New York City, meanwhile, contained a variety of people and religions—as well as Dutch and English people, and it held French Protestants (Huguenots), Jews, Puritans, Quakers, Anglicans, and a large population of slaves.

As they did in other zones of colonization, indigenous peoples played a key role in shaping the history of colonial New York. After decades of war in the 1600s, the powerful Five Nations of the Iroquois, composed of the Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga, and Seneca, successfully pursued a policy of neutrality with both the English and, to the north, the French in Canada during the first half of the 1700s. This policy meant that the Iroquois continued to live in their own villages under their own government while enjoying the benefits of trade with both the French and the English.

The Dutch West India Company had introduced slavery in 1625. Although enslaved, the Africans had a few basic rights and families were usually kept intact. Admitted to the Dutch Reformed Church and married by its ministers, their children could be baptized. Slaves could testify in court, sign legal documents, and bring civil actions against whites. Some were permitted to work after hours earning wages equal to those paid to white workers. When the colony fell, the company freed all its slaves, establishing early on a nucleus of free blacks.

New Jersey

European colonization of New Jersey started soon after the 1609 exploration of its coast and bays by Henry Hudson. The original inhabitants of the area included the Hackensack, Tappan, and Acquackanonk tribes in the northeast, and the Raritan and Navesink tribes in the center of the state.

Soon after the English had gained control of New Netherland, James granted the land between the Hudson and Delaware rivers to two friends who had been loyal to him through the English Civil War and named it New Jersey after the English Channel Island of Jersey. The two proprietors of New Jersey attempted to augment their colony's population by granting sections of lands to settlers and by passing a document granting religious freedom to all inhabitants of New Jersey. In return for land, settlers paid annual fees known as quitrents. Land grants made in connection to the importation of slaves were another enticement for settlers.

After one of the proprietors sold part of the area to the Quakers, New Jersey was divided into East Jersey and West Jersey—two distinct provinces of the proprietary colony. The political division existed from 1674 to 1702. The border between the two sections reached the Atlantic Ocean to the north of Atlantic City. Much of the territory was quickly divided after 1675, leading to the distribution of land into large tracts that later led to real estate speculation and subdivision. In 1702, the two provinces were reunited under a royal, rather than a proprietary, governor. The governors of New York then ruled New Jersey, which infuriated the settlers of New Jersey, who accused the governor of showing favoritism to New York. In 1738, King George II appointed a separate governor for New Jersey.

Since the area's settlement, New Jersey has been characterized by ethnic and religious diversity. New England Congregationalists settled alongside Scottish Presbyterians and Dutch Reformed migrants. While the majority of residents lived in towns with individual landholdings of 100 acres, a few rich proprietors owned vast estates. English Quakers and Anglicans owned large landholdings. Unlike Plymouth, Jamestown, and other colonies, New Jersey was populated by a secondary wave of immigrants who came from other colonies instead of those who migrated directly from Europe.

New Jersey remained agrarian and rural throughout the colonial era, and commercial farming developed only sporadically. Some townships emerged as important ports for shipping to New York and Philadelphia. The colony's fertile lands and tolerant religious policy drew more settlers, and New Jersey boasted a population of 120,000 by 1775.