Meso-American civilizations were amongst some of the most powerful and advanced civilizations of the ancient world. Reading and writing were widespread throughout Meso-America and these civilizations achieved impressive political, artistic, scientific, agricultural, and architectural accomplishments. Many of these civilizations gathered the political and technological resources to build some of the largest, most ornate, and highly populated cities in the ancient world.

The aboriginal Americans settled in the Yucatán peninsula of present-day Mexico around 10,000 BCE. Archaeological, historical, and linguistic evidence suggests that the Nahua peoples originally came from the deserts of northern Mexico, where they lived alongside the Cora and Huichol, and the southwestern United States. They migrated into central Mexico in several waves. The first group of Nahuas to split from the main group were the Pochutec. The Pochutec went on to settle the Pacific coast of Oaxaca, possibly as early as 400 CE. From c. 600 CE, the Nahua quickly rose to power in the places where they had settled in central Mexico and expanded into areas earlier occupied by Oto-Manguean, Totonacan, and Huastec peoples.

Telamones Tula

Toltec warriors were represented by the famous statues of Atlantis in Tula.

From this period on, the Nahua were the dominant ethnic group in the Valley of Mexico and beyond, with migrations continuing to come in from the north. One of the final Nahua migrations to arrive in the valley settled on an island in Lake Texcoco c. 1200 CE and proceeded to subjugate the surrounding tribes. This group were the Mexica who, over the course of the next 300 years, became the dominant ethnic group of Meso-America, ruling from Tenochtitlan, their island capital. Allying with the Tepanecs and Acolhua people of Texcoco, they formed the Aztec empire, spreading the political and linguistic influence of the Nahuas well into Central America.

The Aztec Confederacy

The Aztec Confederacy began a campaign of conquest and assimilation. Outlying lands were inducted into the empire and became part of the complex Aztec society. Local leaders could gain prestige by adopting and adding to the culture of the Aztec civilization. The Aztecs, in turn, adopted cultural, artistic, and astronomical innovations from its conquered people.

The heart of Aztec power was economic unity. Conquered lands paid tribute to the capital city, Tenochtitlan, the present-day site of Mexico City. Rich in tribute, this capital grew in influence, size, and population. When the Spanish arrived in 1521, it was the fourth largest city in the world (including the once independent city Tlatelco, which was by then a residential suburb) with an estimated population of 212,500 people. It contained the massive Temple de Mayo (a twin-towered pyramid 197 feet tall), 45 public buildings, a palace, two zoos, a botanical garden, and many houses. Surrounding the city and floating on the shallow flats of Lake Texcoco were enormous chinampas—floating garden beds that fed the many thousands of residents of Tenochtitlan.

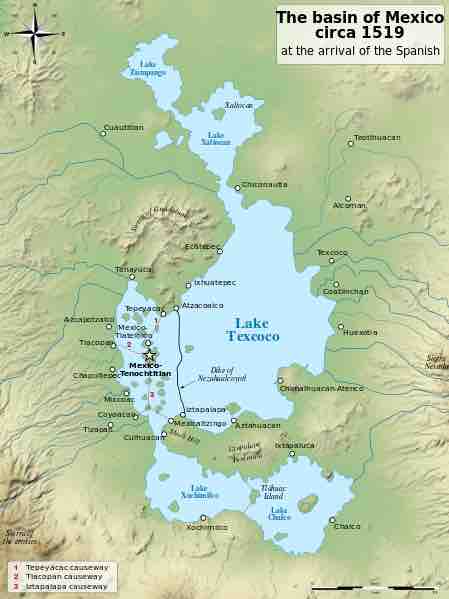

The basin of Mexico circa 1519 at the arrival of the Spanish

The Aztec Empire was based in the Basin of Mexico, pictured here. The capital, Mexico-Tenochtitlan, was located on an island in Lake Texcoco.

Aztec Family and Lineage

Family and lineage were the basic units of Aztec society. One’s lineage determined one’s social standing, and noble lineages were traced back to the mythical past with nobles being said to descend from Quetzalcoatl. Many prestigious lineages also traced their kin back through ruling dynasties, most often ones with Toltec heritage, which was considered favorable. The extended family group was the basic social unit and living patterns were determined by family ties, with networks of family groups settling together to form calpollis. Lineage was traced back via both the father and mother’s ancestry, however, paternal lineage was favored.

Aztec Religion

The Aztecs practiced a religion that was polytheistic and recognized a large and ever increasing pantheon of gods and goddesses. The Aztecs would even incorporate deities who came from other geographic regions or peoples into their own religious practices. The most important celestial entities in the Aztec religion were the Sun, the Moon, and the planet Venus (referred to as both the “morning star” and “evening star”). All these entities had different symbolic and religious meanings as well as associations with certain deities and geographical places.

Many of the leading deities of the Aztec pantheon were worshiped by previous Meso-American civilizations, such as Tlaloc, the rain god; Quetzalcoatl, the feathered serpent; and Tezcatlipoca, the god of destiny and fortune. Each of these gods had their own shrine, side-by-side, at the top of the largest pyramid in the Aztec capital. A common Aztec religious practice was to recreate the divine through sacred impersonation. Mythological events were ritually recreated and living persons would impersonate the specific deities involved. The people impersonating deities were treated with reverence once they were in their roles, some even living in splendor and luxury up to a year prior to the religious ceremony in which they were to perform. Many such ritual actors, however, were typically sacrificed to the very deity they had represented during the ceremony.

While many Meso-American civilizations practiced human sacrifice, none performed it to the scale of the Aztecs. To the Aztecs, human sacrifice was a necessary appeasement to the gods. According to their own records, one of the largest slaughters ever performed occurred when the great pyramid of Tenochtitlan was reconsecrated in 1487. The Aztecs reported that they had sacrificed 84,400 prisoners over the course of four days.

The Arrival of the Spanish

The Spanish arrival at Tenochtitlan marked the downfall of Aztec culture. Although shocked and impressed by the scale of Tenochtitlan, the display of massive human sacrifice offended European sensitivities, and the abundant displays of gold and silver inflamed their greed. The Spanish killed the reigning ruler, Montezuma, in June 1520 and lay siege to the city. They destroyed it completely in 1521, aided by their alliance with a competing tribe, the Tlaxcala.

The Maya Civilization

The Maya civilization was a Meso-American civilization developed by the Maya peoples in an area that encompasses southeastern Mexico, all of Guatemala and Belize, as well as the western portions of Honduras and El Salvador. The region consists of the northern lowlands encompassing the Yucatán Peninsula and the highlands of the Sierra Madre. The Maya civilization is the only known pre-Columbian society to have fully developed its own writing system. It is also notable for its advances in art, architecture, mathematics, as well as the development of a unique calendar and astronomical system.

The first developments in agriculture and the first villages of the Maya civilization appeared during the Archaic period prior to 2000 BCE. The establishment of the first complex societies in the Maya region, including cultivation of the staple crops of the Maya diet—maize, beans, squashes, and chili peppers—occurred in the Preclassic period c. 2000 BCE to 250 CE. The first Maya cities developed around 750 BCE, and by 500 BCE, these cities possessed monumental architecture, including large temples with elaborate stucco façades. Beginning around 250 CE, during the Classic period, the Maya civilization developed a large number of city-states linked by a complex trade network. During this same time, the central Mexican city, Teotihuacan, was becoming increasingly intrusive in Maya dynastic politics. By the 9th century, the central Maya region experienced political collapse, resulting in internecine warfare, the abandonment of some cities, and a northward shift in population. The last Maya city fell to the Spanish in 1697 during the colonization of the Meso-American region.

Maya Society and Family

Since the early Preclassic period, Maya society was divided into elite and common classes. Over time, as the population increased and urban centers grew, the wealthy segment of society multiplied, and a middle class may also have developed, comprised of artisans, low-ranking priests and officials, soldiers, and merchants. Property was held communally by noble houses or clans, according to indigenous histories, and connections to land were established and maintained via a strong connection to ancestry, with many deceased ancestors being buried in residential compounds. Many families even buried their dead underneath the floorboards of their home.

Maya lineages were patrilineal, so household shrines to prominent male ancestors would often decorate residential compounds. As elites became more powerful, these shrines evolved into grand pyramid structures to house the remains of deceased royals.

Maya Religion

The Maya, like many Meso-American peoples, believed in a pantheon of deities, which were routinely placated with ceremonial offerings and ritual practices. Deceased ancestors played a significant role as intercessors between deities and human beings. Shamans also acted as early intercessors between humanity and the supernatural. Over time, political elites codified the ritualistic Maya practices into religious cults that justified the ruler’s claim to power. By the late Preclassic period, this culminated in the concept of a divine kingship.

The Maya believed in a highly codified cosmos, with 13 levels within heaven and nine levels subsumed within the underworld. The supernatural pervaded every aspect of Maya life, and Maya deities governed all aspects of the world. Public ceremonies incorporated aspects of feasting, bloodletting, incense burning, music, ritual dance, and even human sacrifice, which became more common in the Postclassic period.