Kansas–Nebraska Act

The allure of rich farmlands and the potential for infrastructure development in the Kansas-Nebraska territories put the Compromise of 1850 to the test. The Missouri Compromise of 1820 had prohibited slavery in all new territories north of the 36° 30' latitude line, effectively banning slavery in the Kansas territory. The Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854, however, drafted by Democrat Stephen A. Douglas (IL), repealed the Missouri Compromise of 1820 and mandated that popular sovereignty would determine any new territory's slave or free status.

The initial purpose of the Kansas-Nebraska Act was to facilitate the growth of farmland throughout the territory and the development of a transcontinental railroad through the Midwest. Douglas and other representatives hoped that by tagging on the popular sovereignty mandate, they could avoid confronting the slave issue in the organization of the Kansas-Nebraska territory. However, the act spurred a mass influx of slave owners and independent farmers into Kansas—and both groups went with the explicit aim of voting for or against slavery in the territory. The result was violence, leading to the events of a conflict known as "Bleeding Kansas."

"Bleeding Kansas"

“Bleeding Kansas” is the term used to refer to the political violence that erupted in Kansas territory and neighboring Missouri towns between proslavery and abolitionist forces. It is considered by many historians to be a precursor to the U.S. Civil War. Kansas territory was neighbors with slave state Missouri and free state Iowa. As activist settlers poured into Kansas territory with the intent of voting for or against slavery as a state-sanctioned institution, politics began to resemble a war rather than democratic balloting. Proslavery settlers came to Kansas mainly from neighboring Missouri, and some residents of Missouri crossed into Kansas solely for the purpose of voting in territorial elections. During the 1855 elections for territory legislature, thousands of “Border Ruffians” from Missouri entered the territory and rigged the ballots, creating a fraudulent majority for proslavery candidates. In response to the "Border Ruffians," antislavery settlers held a separate convention to elect their own candidates to the legislature. Proslavery groups, in turn, attacked the city of Lawrence, and John Brown, a radical abolitionist, led attacks on proslavery settlers nearby. Hostilities between the factions reached a state of low-intensity civil war, damaging Franklin Pierce's administration as the nascent Republican Party sought to capitalize on the scandal of "Bleeding Kansas" in the upcoming election.

Congress

Though the situation in Kansas territory was descending quickly into anarchy, Congress was too preoccupied with its own internal conflicts to effectively intervene. On May 22, 1856, as Senator Charles Sumner (MA) gave a speech on the violent situation in Kansas, likening the proslavery invasion of the territory to the “rape of a virgin,” Senator Preston Smith Brooks (SC) physically attacked Sumner with his cane. News of the incident shocked the nation and served to further polarize proslavery and antislavery factions. To many Northerners, Sumner was considered an antislavery martyr for standing up for his convictions. To many Southerners, however, the incident provided another example of how abolitionists were willing to use Congress as a forum to attack Southern honor, culture, and economic practices.

Southern Democrats were pleased that the Kansas-Nebraska Act repealed the Missouri Compromise, while Northerners (including Northern Democrats) decried the opening of territory to slave owners where slavery had previously been prohibited for more than 30 years. Already a fractured party, the Whigs collapsed and made way for the Northern-dominated Republican Party: a coalition of Free-Soilers, Northern Democrats, and antislavery forces that bitterly resented the repeal of the Missouri Compromise. This, in turn, gave rise to the Know-Nothing Party, a political movement composed of ex-Whigs looking for a vehicle to fight the dominant Democratic Party. In 1854, former congressman Abraham Lincoln publicly aired his moral, legal, and economic arguments against the expansion of slavery, as well as his opposition to the Kansas-Nebraska Act in three separate speeches in Illinois.

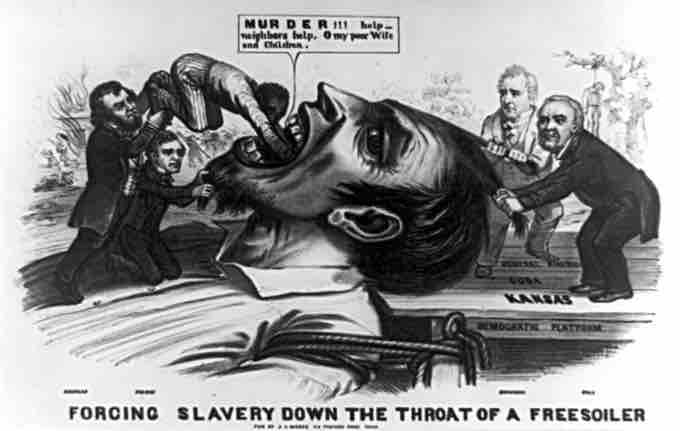

"Forcing Slavery Down the Throat of a Free-Soiler"

An 1854 cartoon depicts a giant Free-Soiler being held down by James Buchanan and Lewis Cass, who stand on the Democratic platform marked "Kansas," "Cuba," and "Central America" (referring to accusations that Southerners wanted to annex areas in Latin America to expand slavery). Franklin Pierce also grips the giant's beard as Stephen A. Douglas shoves a black man down his throat.

However, with the support of President Pierce, Douglas pushed the act through Congress, albeit with rigidly delineated sectional votes. For many Northern politicians, the Kansas-Nebrasaka Act was the latest in a string of proslavery laws that revealed the South's aim to aggressively expanded slavery into every state in the Union.

In 1861, Kansas was admitted to the Union as a free state in the midst of the Civil War. Nebraska was not admitted to the Union until 1867, after the Civil War.