Background and Context

Located 90 miles off the coast of Florida, Cuba had been considered a target for annexation by several presidential administrations. President John Quincy Adams described Cuba and Puerto Rico as, “natural appendages to the North American continent,” and Cuba's annexation as, “indispensable to the continuance and integrity of the Union itself.” The Spanish empire had been in gradual decline, but so long as control of Cuba did not pass to a stronger power such as Britain or France, most presidential administrations did not aggressively seek annexation.

As the sectional debate over expansion intensified, however, Southern Democrats began to look to Cuba as another potential slave state. Slavery was a centuries-old institution in Cuba, and its sugar plantation system, overall agrarian economy, and location predisposed it to the agricultural interests of the South. Hence it was believed that the annexation of Cuba might greatly strengthen the position of Southern slaveholders against industrial Northern interests. The movement for annexation grew even more intense as free states from the Western territories were admitted to the Union and political conflict erupted in the wake of the Kansas-Nebraska Act, upsetting the already delicate balance of power between slave and free states in the Senate.

Ostend Manifesto

At the suggestion of Secretary of State William L. Marcy, U.S. Minister to Spain Pierre Soulé met with U.S. Minister to Great Britain James Buchanan and U.S. Minister to France John Y. Mason at Ostend, Belgium, to discuss the Cuba matter. The resulting dispatch, drafted at Aix-la-Chapelle in October 1854, outlined the reasons the U.S. purchase of Cuba would be beneficial to all parties involved and declared that the United States would be "justified in wresting" the island from Spanish hands if Spain refused to sell. Prominent among the reasons for annexation outlined in the Ostend Manifesto were fears of a possible slave revolt in Cuba, the likes of which had already occurred in Haiti, in the absence of U.S. intervention. Racial fears raised tension and anxiety over a potential black uprising on the island that could "spread like wildfire" to the United States.

To Marcy's chagrin, the flamboyant Soulé made no secret of the diplomatic meetings, causing unwanted publicity in both Europe and the United States. In the increasingly volatile political climate of 1854, the Franklin Pierce administration feared the political repercussions of making the negotiations known, but pressure from journalists and politicians alike to publish what was agreed to in Ostend continued to mount. As a result, the dispatch was published in full at the behest of the House of Representatives. Dubbed the Ostend Manifesto, it was immediately denounced in both Northern U.S. states and Europe. It became a rallying cry for Northerners in the events that would later be termed "Bleeding Kansas," and the political fallout was a significant setback for the Pierce Administration.

Fallout

When the document was published, it outraged Northerners, who viewed it as an aggressive Southern attempt to extend slavery. American Free-Soilers, recently angered by the Fugitive Slave Law (passed as part of the Compromise of 1850), decried the Manifesto, dubbed by Horace Greeley of the New York Tribune as “The Manifesto of the Brigands”, unconstitutional. The Pierce administration was irreparably damaged by the incident, and Northern Democrats began to withdraw their support and gravitate toward the nascent Republican Party.

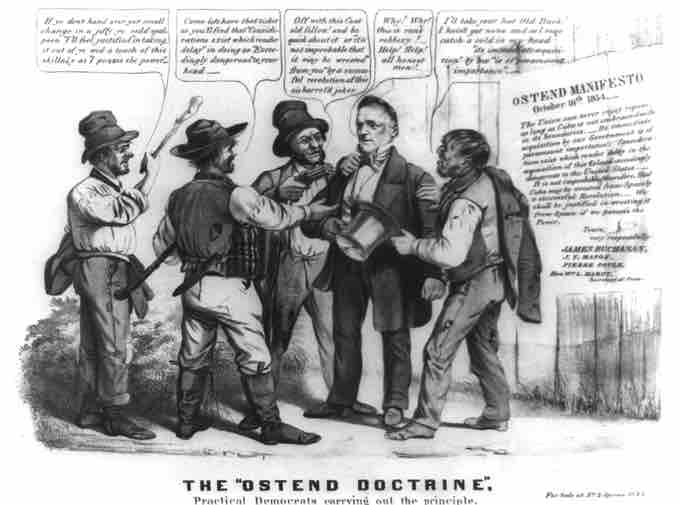

Cartoon of the Ostend Doctrine

A political cartoon depicts James Buchanan surrounded by hoodlums using quotations from the Ostend Manifesto to justify robbing him.

Internationally, the Ostend Manifesto was seen as a threat not only to Spain, but also to all imperial powers across Europe. It was quickly denounced in Madrid, London, and Paris. To preserve what favorable relations the administration had left, Soulé was ordered to cease discussion of Cuba, and he promptly resigned. The backlash from the Ostend Manifesto shelved any expansionist plans for Cuba for several decades. The “Cuban Question” would not dominate U.S. foreign policy discussions until 30 years after the Civil War.

Portrait of Pierre Soulé

Pierre Soulé, the driving force behind the Ostend Manifesto and its resultant political fallout.