California As a Free or Slave State

In the immediate aftermath of the Mexican War and in the midst of the California Gold Rush, a major political confrontation occurred in Congress that required many compromises in order to prevent Southern secession.

As part of their application for annexation, California settlers proposed that their state would ban slavery. However, the admission of California as a free state would tip the balance of power in the Senate. Southern politicians, alarmed that they would lose their majority, pushed for Congress to pass legislation that would allow California to be admitted as a slave state, or to extend the Missouri Compromise line to the Pacific, effectively splitting the state in half into one free state and one slave state. Pushing the issue even further, many Southern politicians argued that the federal government had no right to interfere in the rights of slave owners to move their property within the boundaries of the nation, including free states.

This prompted a series of measures designed to appease both Northern and Southern congressmen via a more equitable balance of power. Henry Clay, the leader of the Whig Party (nicknamed the "Great Pacificator”) drafted the following five compromise measures in 1850:

- California becomes a free state, and Texas's boundary would remain at its present-day limits.

- The United States would pay Texas $10 million in compensation for the loss of New Mexico territory, which Texas had previously claimed as part of its state territory.

- The territories of New Mexico and Utah would be organized on the basis of popular sovereignty.

- The Fugitive Slave Act of 1850 would be passed into law.

- The slave trade would be abolished in the District of Columbia.

These measures, passed through Congress in September 1850, solved the dispute regarding California's status as free versus slave, but did not provide any long-term, fundamental principle for future decisions on the sectional balance of new territories. By allowing popular sovereignty to determine slave or free states, the Senate basically guaranteed future discord over the sectional balance of power in the coming years. During the debates over California, Northern senators argued that settlers (in any territory) could curtail or ban slavery at will, while Southerners claimed that there could be no prohibition of slavery in the territories because the land belonged to all states equally. In the Compromise of 1850, popular sovereignty was not defined as a guiding principle on the slave issue going forward. Furthermore, the bill's strengthening of the Fugitive Slave Act angered many Northerners, and even provoked violence in Northern cities. In short, the Compromise of 1850 was less an effective tool for federal management of western territories and more a precarious stalemate agreed to by the North and the South that effectively shelved the slave problem for a few more years.

Nonetheless, the Compromise of 1850 was perceived by both sides as a success insofar as it staved off a greater escalation of sectional conflict. During the debate over the Compromise, John C. Calhoun, a notable defender of the South and Southern slavery, wrote an ominous speech that anticipated secession and disunion if the Northern states did not meet Southern demands. This led some politicians to accept what otherwise would have been an unacceptable bill out of fear of raising the stakes of the conflict. Senator Daniel Webster of Massachusetts, for example, spoke in favor of the Compromise, urging Northerners to abandon radical antislavery legislation while warning the South that threats to secede would inevitably result in sectional violence. Many Northern abolitionists later denounced Webster for agreeing to the “devil's compromise”; however, many politicians were relieved to enact temporary measures to keep the peace between the states.

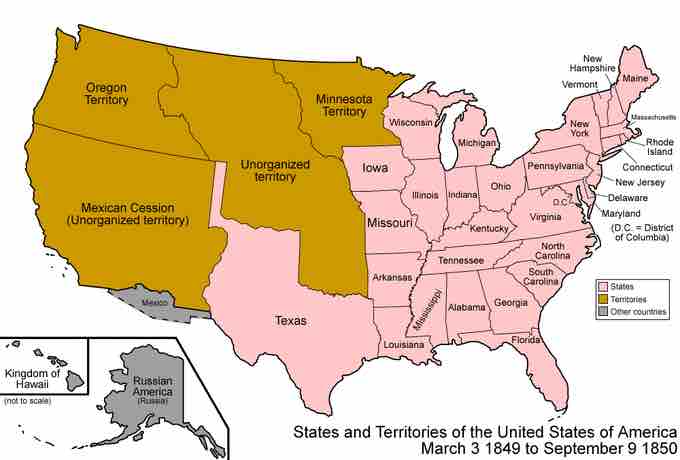

The United States, 1849–1850

A map of the United States depicting states and territories, and land held by other countries during the time period of 1849–1850.