During the industrial era, cities grew rapidly and became centers of population and production. The growth of modern industry from the late 18th century onward led to massive urbanization and the rise of new, great cities, first in Europe, and then in other regions, as new opportunities brought huge numbers of migrants from rural communities into urban areas. In 1800, only 3% of the world's population lived in cities. Since the industrial era, that figure, as of the beginning of the 21st century, has risen to nearly 50%. The United States provides a good example of how this process unfolded; from 1860 to 1910, the invention of railroads reduced transportation costs and large manufacturing centers began to emerge in the United States, allowing migration from rural to urban areas.

Rapid growth brought urban problems, and industrial-era cities were rife with dangers to health and safety. Rapidly expanding industrial cities could be quite deadly, and were often full of contaminated water and air, and communicable diseases. Living conditions during the Industrial Revolution varied from the splendor of the homes of the wealthy to the squalor of the workers. Poor people lived in very small houses in cramped streets. These homes often shared toilet facilities, had open sewers, and were prone to epidemics exacerbated by persistent dampness. Disease often spread through contaminated water supplies.

In the 19th century, health conditions improved with better sanitation, but urban people, especially small children, continued to die from diseases spreading through the cramped living conditions. Tuberculosis (spread in congested dwellings), lung diseases from mines, cholera from polluted water, and typhoid were all common. The greatest killer in the cities was tuberculosis (TB). Archival health records show that as many as 40% of working class deaths in cities were caused by tuberculosis.

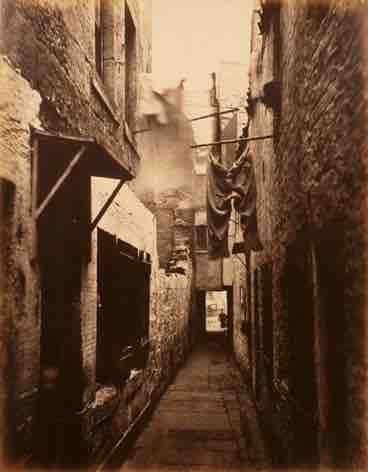

Slum in Glasgow, 1871

An example of slum life in an industrial city.