The body responds to stress in certain physiological ways. When a threat or danger is perceived, the body responds by releasing hormones that will prepare it for the fight-or-flight response. The main physiological structure involved in this response is known as the HPA (hypothalamic–pituitary gland–adrenal gland) axis. Such interactions of the endocrine hormones have evolved to ensure that the body's internal environment remains stable; however, stress can disrupt this stability. Stimuli that disrupt homeostasis in this way are known as stressors.

The Fight-or-Flight Response

When our bodies are faced with a stressor—any trigger that leads to a stress response—certain physical processes take place. The body reacts in a primitive sense to what it perceives as impending danger in what is colloquially termed the fight-or-flight response (sometimes "fight-flight-or-freeze"). Blood from your skin, organs, and extremities is directed to the brain and larger muscles in preparation to fight the impending danger or flee from it. In addition, your senses (especially vision and hearing) are heightened, glucose and fatty acids are released into the blood stream for energy, and your immune and digestive systems all but shut down to provide you with the necessary energy to fight the stressor. The HPA axis coordinates all these physiological changes. Health psychology focuses on this physical reaction and what it means for a person's health and well-being.

Observable Symptoms of Stress

Stress produces numerous symptoms that vary according to person, situation, and severity. Problems resulting from stress include decline in physical health or mental health, a sense of being overwhelmed, feelings of anxiety, overall irritability, insecurity, nervousness, social withdrawal, loss of appetite, depression, panic attacks, exhaustion, high or low blood pressure, skin eruptions or rashes, insomnia, lack of sexual desire (sexual dysfunction), migraine, gastrointestinal difficulties (constipation or diarrhea), heart problems, and menstrual symptoms.

Stress and the body

This diagram shows the effects of stress on various parts and systems of the body.

The HPA Axis

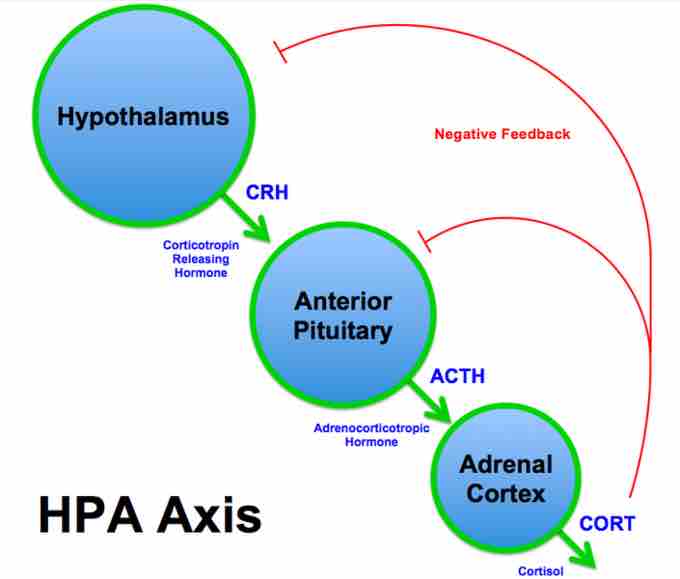

The hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis (HPA axis) is a complex set of direct influences and feedback interactions among three endocrine glands: the hypothalamus, the pituitary gland, and the adrenal glands. The HPA axis is a major part of the neuroendocrine system that, among other things, controls reactions to stress.

The HPA system reacts within a person's brain, and it releases the hormone cortisol from the adrenal gland when a person is exposed to a stressor. Cortisol is most likely to be activated when a person is placed in a situation to be socially judged or evaluated, and therefore under extreme levels of stress. Higher and more prolonged levels of cortisol in the bloodstream are found in those suffering from chronic stress.

The stress response

The sympathetic nervous system regulates the stress response via the hypothalamus.

Although our bodies can respond to and deal with stress in the short term, long-term exposure to stress hormones can have detrimental effects. For example, it can lead to a decrease in memory function and physical performance. This is because glycogen reserves, which provide energy in the short-term response to stress, are exhausted after several hours and cannot meet long-term energy needs. If glycogen reserves were the only energy source available, neural functioning could not be maintained once the reserves became depleted due to the nervous system's high requirement for glucose.

Stress Hormones and Sympathetic Nervous System

The following are simplified steps that a person's nervous system goes through when it deals with a stressful situation:

- Blood from the skin, internal organs, and extremities, is directed to the brain and large muscles in preparation for "fight" or "flight."

- Your senses are heightened, especially vision and hearing.

- Glucose and fatty acids are forced into the bloodstream for energy.

- The immune and digestive systems are virtually shut down to provide all the necessary energy to respond to the perceived threat.

The sympathetic nervous system regulates the stress response via the hypothalamus. Stressful stimuli cause the hypothalamus to signal the adrenal medulla (which mediates short-term stress responses) via nerve impulses, and the adrenal cortex (which mediates long-term stress responses) via the hormone adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), which is produced by the anterior pituitary. When presented with a stressful situation, the body responds by calling for the release of hormones that provide a burst of energy. The hormones epinephrine (also known as adrenaline) and norepinephrine (also known as noradrenaline) are released by the adrenal medulla.

Epinephrine and norepinephrine increase blood glucose levels by stimulating the liver and skeletal muscles to break down glycogen, and by stimulating glucose release by liver cells. Additionally, these hormones increase oxygen availability to cells by increasing the heart rate and dilating the bronchioles. The hormones also prioritize body function by increasing blood supply to essential organs such as the heart, brain, and skeletal muscles, while restricting blood flow to organs not in immediate need, such as the skin, digestive system, and kidneys. Epinephrine and norepinephrine are collectively called catecholamines.

Experimental Research on the Effects of Stress

Research has found that maintaining good health has a positive influence on reducing and coping with stress. Behaviors such as exercise, meditation, deep breathing, good eating habits, and getting enough sleep can help individuals better handle stress and avoid negative effects such as increased likelihood of sickness and poor digestion. Unfortunately, stress can have a negative impact on the motivation to maintain these healthy behaviors.

While psychological stress alone has not been proven to cause cancer, prolonged psychological stress may affect a person's overall health and ability to cope with cancer. Evidence from experimental studies suggests that psychological stress levels can affect a tumor's ability to grow and spread. Studies in mice and human cancer cells grown in a laboratory have found that the stress hormone norepinephrine may promote angiogenesis and metastasis. "Angiogenesis" refers to the development and formation of new blood vessels. "Metastasis" refers to the transference of a bodily function or disease to another part of the body, specifically the development of a secondary area of disease remote from the original site.