Conformity is the most common and pervasive form of social influence. It is informally defined as the tendency to act or think like members of a group. In psychology, conformity is defined as the act of matching attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors to group norms. While conformity is often viewed as a negative characteristic in American culture, it is very common. While high levels of conformity can be detrimental, a certain amount of conformity is necessary and normal, and even essential for a community to function. It is generally distinguished from obedience (behavior influenced by authority figures) and compliance (behavior influenced by peers).

Motivations Underlying Conformity

Conformity may result from either subtle, unconscious influences or direct and overt social pressure. It does not require the physical presence of others to occur—that is, knowledge of public opinion may cause an individual to conform to societal norms even when alone. There are two major motivators to conformity: normative influence and informational influence. Normative influence occurs when an individual conforms in order to gain social acceptance and avoid social rejection. For instance, men's and women's views of what the ideal body image is have changed over time. Both men and women will conform to current norms in order to be accepted by society and avoid social rejection.

Informational influence occurs when individuals seek out members of their own group to obtain and accept accurate information about reality. For instance, if Susan lands a really prestigious, high-paying job, she is more likely to be offered similarly high-paying jobs in the future because potential employers will be influenced by their peers' previous decisions about her. The opposite effect is true as well: if Susan has been unemployed for a long time, employers may assume it is because others have not wanted to hire her. They will, therefore, try harder to find flaws in her and her application.

A number of factors are known to increase the likelihood of conformity within a group. Some of these are as follows:

- Group size—larger groups are more likely to conform to similar behaviors and thoughts than smaller ones.

- Unanimity—individuals are more likely to conform to group decisions when the rest of the group's response is unanimous.

- Cohesion—groups that possess bonds linking them to one another and to the group as a whole tend to display more conformity than groups that do not have those bonds.

- Status—individuals are more likely to conform with high-status groups.

- Culture—cultures that are collectivist exhibit a higher degree of conformity than individualistic cultures.

- Gender—women are more likely to conform than men in situations involving surveillance, but less likely when there is no surveillance. Societal norms establish gender differences that affect the ways in which men and women conform to social influence.

- Age—younger individuals are more likely to conform than older individuals, perhaps due to lack of experience and status.

- Importance of stimuli—individuals may conform less frequently when the task is considered important. This was suggested by a study where participants were told that their responses would be used in the design of aircraft safety signals, and conformity decreased.

- Minority influence—minority factions within larger groups tend to have influence on overall group decisions. This influence is primarily informational and depends on consistent adherence to a position, the degree of defection from the majority, and the status and self-confidence of the minority members.

Research on Conformity

Asch

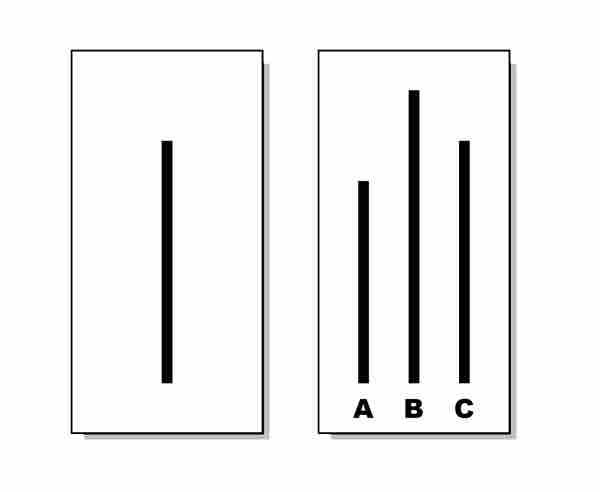

Solomon Asch's conformity experiments are one of the best-known illustrations of conformity. His initial experiment in 1951 was set up as follows. The research participant was told he was participating in a simple "perceptual" task. The participant would enter a room and sit at a table with several other people. These people were confederates, or individuals who were posing as other participants but were really working for the researchers. The participant and confederates would be shown a series of cards that had a reference line and another card that had three comparison lines. Over the course of several trials, subjects were required to select the comparison line that corresponded in length to the reference line. The participant and confederates were instructed to provide their answers out loud, and the confederates were told to sometimes unanimously provide a correct answer and sometimes an incorrect answer. When Asch had the confederates all choose the same obviously incorrect answer, participants also chose the wrong line 37% of the time. In a control group with no pressure to conform, participants had an error rate of less 1%.

Solomon Asch and conformity

The image shown is an example from Solomon Asch's landmark experiment in conformity (1951). An individual was asked to state which line, A, B, or C, matched the first line. If the other members of the group gave an obviously incorrect response, the participant was more likely to also give an obviously incorrect response (A or B).

Asch repeated this experiment with different experimental variables and identified several factors that influence conformity. Presence of a true partner, who was another real participant and gave the correct response, decreased levels of conformity. Removing this partner halfway through the study caused increased levels of conformity after their departure. Group size also influenced levels of conformity such that smaller groups resulted in less conformity than larger groups. Public responses, those that were spoken in the presence of the confederates, were associated with higher levels of conformity than private, written responses.

Sherif

Muzafer Sherif was interested in knowing how many people would change their opinions to bring them in line with the opinion of a group. In his experiment (1936), participants were placed in a dark room and asked to stare at a small dot of light 15 feet away. They were then asked to estimate the amount it moved; however, there was no real movement. Perceived motion was caused by the visual illusion known as the autokinetic effect. On the first day, each person perceived different amounts of movement, as they participated in the experiment individually. From the second through the fourth day of the study, estimates were agreed upon by the group. Because there was no actual movement, the number that the group agreed on was a direct result of group conformity. Sherif suggested this was a reflection of how social norms develop in larger society.